[ad_1]

IIt is difficult for Miles to determine when his muscular dysmorphia began. It was just always there, a background sound. "As far as I can remember, I wanted a more beautiful body," said the 35-year-old US soldier currently serving in Mons, Belgium. At the age of 13, Miles spent the summer chopping grbad in order to book himself an occasional Soloflex exercise machine. The machine cost $ 1,000, but since Miles was too young to enroll in a gym, it was worth it. With the help of the Soloflex, Miles started doing weight training and never looked back.

When he returned from a mission in Afghanistan at the age of 24, things accelerated. He started working obsessively and organizing his meals. "I went all out … it was an unconditional dedication to lifestyle." Miles set his watch to beep every three hours to remind him to eat. If he beeped while driving, he would stop. Slowly, he shaped his body. His muscles became striated, each fiber visible. Not big enough. At 95kg and 1.8m, Miles wanted to be more muscular. thinner. He lost 22 kg and started competing in amateur bodybuilding. There was virtually no fat on him. "You pinch your skin and it stays pinched." His girlfriend left him. "She began to understand that my body dysmorphic was as if I was going out with another person." The pursuit of the musculature resumed its life. "I was just thinking: I'm so skinny, shredded, lively and masculine – I never want to go back to what I was before."

Yet at age 33, single again – the dysmorphic had claimed another relationship – everything had become too much and he was in a dark place. "I did not enjoy any way of life." Throughout the day, he was starving, struggling with hard training sessions, returning home and gorging himself before spoiling everything. . One evening, queuing at the In-N-Out hamburger chain for more food to purge, Miles finally decided that it was enough. "I woke up so happy the next day, knowing it was over."

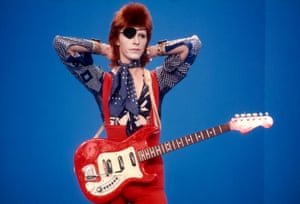

"In the 1970s, we saw very thin, almost androgynous men like Mick Jagger and David Bowie (…) being muscular, which was to be defined as militaristic." Photo: Peter Mazel / Sunshine / Rex / Shutterstock

A subgroup of body dysmorphic disorders, people with muscular dysmorphia feel that they should become bigger or more muscular, regardless of their size. Sometimes called "bigorexia", it usually affects men. About 30% of people with muscular dysmorphia will also have a medically diagnosable diet disorder – although, as you must be in a calorie deficit to be diagnosed with a eating disorder, many men with do not meet the clinical threshold restrictive diets. Because men with muscular dysmorphia rarely use treatment, it is difficult to badess their prevalence in the general population, but it is estimated that about 10 to 12% of professional weightlifters meet the criteria.

And muscular dysmorphism may be on the rise. A study published in June found that 22% of men aged 18 to 24 reported eating disorders related to their musculature. "The quest for a bigger, muscular body is becoming widespread," says Dr. Jason Nagata, a senior researcher at the University of California at San Francisco. Muscular dysmorphia does not reach all those who weigh 180 kg. It's when the training takes over your life, including everything else – work, family, friends – that you have a problem. "The whole day is spent in the gym trying to put on weight," says Nagata. "They can also take illicit supplements like steroids."

What is driving a generation of young men to slavishly pursue this physical ideal? "Over the last few decades, the idealized male body image has become bigger and bigger," says Nagata.

This type of body has even penetrated into the room of our children: studies show that the figures have become more muscular in the last 25 years.

It's not always the case. "In the 1970s, we saw very thin, almost androgynous men, like Mick Jagger and David Bowie (…) being muscular, it was being defined as being militaristic, at a time when, in the United States, United, there were demonstrations against Vietnam. war, "says Dr. Roberto Olivardia of Harvard Medical School, a specialist in male body image. "So this construction was really frowned upon and rejected by the youth culture.

"But then, the 80s came into being, with personalities like Ronald Reagan, who was pro-military, and men like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone." This ideal male – hyper-masculine, militarist, strong above all – has been exported worldwide through such films as First Blood (1982), Predator (1987) and The Terminator (1984). WWE Wrestling was founded in 1980 and Hulk Hogan became a celebrity. In the late '90s, a leaner but still muscular aesthetic – popularized by Brad Pitt in the movie Fight Club – became fashionable.

Today's muscular men are staring at us from superhero movie billboards featuring stars like Chris Hemsworth or Jason Momoa, who last week only had a blast of the body after taking pictures showing him having fun on vacation in conditions slightly inferior to those of superheroes. On the small screen, the current crop of Love Island candidates are pampering themselves in the tiny swimsuits for the cameras, so as to display their perfect six pack.

However, just as fashion magazines do not cause anorexia, but contribute to a toxic environment in which one celebrates extreme thinness, Hulk Hogan, Dwayne 'The Rock' Johnson and Chris Hemsworth should not be held responsible for the behaviors messy that sweep our gyms. According to the NHS, we do not yet know what causes the disorders of body dysmorphism, but genetics, a chemical imbalance in the brain or a traumatic experience in your past can play a role. You are also more likely to develop it if you were bullied or child, something student Nathaniel Shaw knows well. The 28-year-old was bullied in high school. They called him a borrower because of his slender figure.

Dwayne 'The Rock' Johnson in Fast & Furious 6. Photo: Universal / Kobal / Rex / Shutterstock

"I've always been the little boy in a corner that no one wanted to talk about." Social acceptance came a crouched press at a time. "I come from Nottingham, because it's a very difficult place, you train to protect yourself. The biggest are the serious people that nobody wants to play with. It was the main thing at first – become big and be taken seriously. "

When Shaw went to college at age 17, he had a plan: to train all winter and reveal his buff body next summer. But when he took off his t-shirt playing football one afternoon, a girl said that Shaw "did not have a chest". He instantly puts his top back on. "I was still not good enough." The derogatory comment destroyed Shaw's fragile esteem; he stepped away from the wreck determined to become even more shredded.

Shaw's life has become: The gym, where you eat huge portions of tuna, pasta and cheese, moves as little as possible to save energy and repeats. Shaw stands out from the contours of normal life. He stayed in bed longer, later and missed exams. He was depressed. "The pursuit of this muscular ideal invades people's lives," says Nagata. "They become obsessed. They can not function in their daily lives outside the pursuit of this ideal and this can lead to depression, lack of schooling or work and loss of their ability to perform basic tasks.

For an observer, Shaw – who weighed 80 kg at 1.7 meters – looked like an badault tank. But that was not the way he saw himself. "I'll be in the gym and say," I look like shit. Everyone would say, "No, you're not, you're huge, I would like to look like that." "Muscular dysmorphia is a disease of perception, and although its victims live in the material world – a place of growling effort, weighted bags and recoverable protein powders – they spend most of their time in an imaginary reality, where they are of incalculable size.Their biceps are swollen watermelons, each muscle as finely streaked as the delicate contours of a seashell.

But even if they end up reaching that physical, it is not enough. As soon as a muscle ideal is reached, a new goal appears. "There's a saying that says," Once you enter a gym, you're still small, "says Rich Selby, a 27-year-old amateur bodybuilder from Cardiff. Miles agrees. "Every muscle could be bigger. I could be leaner. You look at yourself and you feel that everything is small and weak. I do not have chest muscles; I do not have muscles in my arms … you judge yourself against an impossible standard. "

Social media reflects this norm at home. "You're selling a false reality," Miles says. "I can be really fit, just before doing a bodybuilding contest, and use lighting, angles and filters to make my physique even crazier than it already is, and back up a lots of photos and upload them to make it look like I still look like this, all year long. "

Some are turning to illegal substances to achieve this ideal. Tony, 23, works for a pharmaceutical distributor in Dallas. He started taking performance-enhancing illegal drugs, including testosterone, balance and nandrolone, two years ago. The drugs created a dangerous feedback loop: the more he injected, the more his body changed and the more he took. "People are like," Wow, this guy is a tank. "They have more respect for you … I said to myself, oh yes, I'm going to take more so that I can become even bigger."

It's a common experience: muscular dysmorphia can be fueled by the positive reinforcement that men receive from other men at the gym. "When you're tall, you get a lot of respect," says Selby. The men approach him and ask him how much he can accumulate. Sometimes they try to start fighting. "That's why people become addicted. They are unsure of their safety, so they need confirmation from others. Selby identifies as having muscular dysmorphia, but feels he has it under control because he has good self-esteem.

From near you can see the damage caused by muscular dysmorphism. "Your interpersonal relationships are getting worse – but you're so trapped in the endorphinic badertion from your fellow sportsmen that you barely notice," Miles says. "You're a bit of a jerk. You do not realize it … you just become this torment all around. It consumes not only all your time and concentration, but also your human share. It's also a solitary existence. All of your time is spent on preparing protein-rich foods, but because you're exercising excessively, you're often "hungry, cranky, and not sleeping well."

Among young men surveyed by Nagata, 2.8% had used illegal steroids and it is estimated that nearly one million Britons are taking performance enhancing drugs. "Steroids can lead to heart disease, kidney problems and liver damage," says Nagata. There are also risks to mental health. "People can be extremely irritable, aggressive, paranoid and can be violent."

Tony was a young man who used drugs to gain mbad. He knew what he was doing was dangerous: he would even donate blood to lower his blood pressure. "I really did not care." While he was drugged, he was experiencing dramatic mood swings. He was fired from a hardware store for yelling at a colleague in the break room. Eventually, his mental health deteriorated so badly that he got rid of all the drugs last May.

"Every muscle could be bigger. I could be leaner. I do not have chest muscles; I do not have muscles in my arms … you judge yourself against an impossible standard. 'Photography: Asked by model / Getty / iStockphoto

What is it that makes someone play Russian roulette with a syringe filled with steroids? Selby believes that people are driven to take desperate measures because they can not separate their identity from their appearance.

It's an obsession that can prove fatal. Freddie Dibben, 28, died in March 2017 after expanding her heart caused by the stimulant Clenbuterol. His father Clifford, 69, found him. "The hardest part was going back to the kitchen and telling her mom what I found. It will never go away. Like Tony, Freddie had mood swings. "He was making fun of you," says Clifford, remembering an incident in which Freddie was "stroppy" with him while they tinkered with his car. He put his mood on stress at work – Freddie worked many hours at night at the Wilton carpet factory, where his colleagues called him a "forklift" because of his carrying capabilities.

But Clifford felt blessed to have a health conscious son; he did not see anything to be alarmed. Freddie, a gym enthusiast, even stopped smoking at the request of his parents. "He had the habit of cooking all his own food! He was preparing a meal before going to work … He had two scales and weighed all his vegetables, everything. He even kept notes of what he was eating and what he was doing. Clifford laughs bitterly. "Except for the bloody drugs."

And this is one of the problems of muscular dysmorphism: you can hide in the sight of all. A pair of scales in the kitchen; Tupperware boxes of chicken and broccoli in your backpack. Most people consider these behaviors to be harmless, although idiosyncratic. And when you have the impression that you are cut in marble, it's hard to think that everything is wrong. It is only when you go past the facade that you realize that these statue-shaped men are slowly destroying each other.

It's a silent epidemic – Olivardia estimates that about 10% of men working in gyms may be suffering but are never seeking help. Recently, Tony started taking illegal substances again, insisting that "it can be done safely." Clifford still has Freddie's scales in the kitchen. Looking at them, he would probably disagree.

•Some of the names in the room have been changed

Source link