[ad_1]

On winter day in 1898, a stocky young man with a handlebar mustache hurried along the banks of a canal in Hamburg, northern Germany. Franz Karl Bühler was panicked, fleeing a gang of mysterious agents who had tormented him for months. There was only one way to escape, he thought. He has to swim for it. So he dove into the dark water, near freezing at this time of year, and walked to the other side. When he was hoisted onto the shore, soaked and shivering, it became obvious to passers-by that there was something strange about this man. There was no sign of his pursuers. He was confused, maybe crazy. He was therefore taken to the nearby Friedrichsberg “madhouse”, as it was then called, and taken inside. He would remain in the dubious care of the German psychiatric system for the next 42 years, one of hundreds of thousands of patients who lived an almost invisible life behind the walls of the asylum.

Bühler’s incarceration disturbs him, but it also marks the beginning of a remarkable story, in which he plays a leading role. It reveals the debt art owes to mental illness and how this connection was used to wage the most destructive culture war in history.

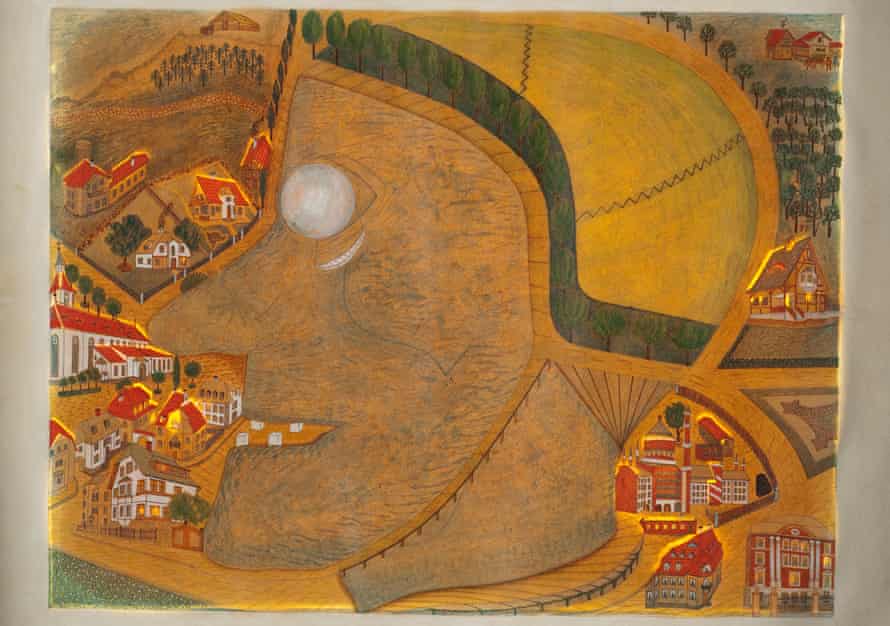

Bühler was diagnosed with schizophrenia and, as he was transferred from one psychiatric clinic to another, he found a way to cope with his situation: he would learn to draw on his own. He began by drawing the people around him, documenting the unnecessary repetitive activities of institutionalized life. He later produced searing self-portraits and garish creatures from his psychotic visions: demonic dogs and angels of death. His doctors cared little for his art – if indeed a “madman” could create art – and many of his sketches lingered in his file for two decades, until the arrival of an important visitor. of Heidelberg.

Hans Prinzhorn was a qualified physician, doctor of art history, decorated soldier and professionally trained baritone. But it was his work on the art of madmen, carried out at the Heidelberg University Psychiatric Clinic, that was to be his greatest achievement. Between 1919 and 1921 he amassed the largest collection of psychiatric art in the world, thousands of pieces of all types, executed with all the varieties of media available – toilet paper, discarded rotas, wooden pieces from asylum beds. – by hundreds of hospitalized patients. Most of them diagnosed with schizophrenia, these individuals did not always intend to make “art”. They used sketches, sculptures and writings to represent aspects of their psychotic reality or to communicate messages from an isolated interior. The initial idea was that this material could aid in the diagnosis, but Prinzhorn soon realized its expressionistic power and artistic merit.

Visitors would notice that it “opened windows to a different reality”, or that it was as if it “sprang from the depths of the human psyche”. “Remarkable worlds opened up before me,” wrote a future curator of the collection, “dragged me into their power; the great outdoors took my balance and made me dizzy. In 1922, Prinzhorn published his findings on the project in a groundbreaking volume, The art of the mentally ill, abundantly illustrated with images from the collection. His greatest discovery, the choice of his “schizophrenic masters”, was Bühler.

Artistic talent became an instant hit with the avant-garde, which by this time was exploring madness as a way to understand the horror it experienced during WWI. As the Dadaist Hans Arp says, “Regretted by the slaughterhouses of the world war, we turned to art”. For Hugo Ball, the co-founder of Dada, Prinzhorn’s book represented nothing less than “the turning point of two eras”.

When Max Ernst took a copy of the book to Paris, it quickly became a essential source for members of the new surrealist movement, including Ernst and Salvador Dalí. Finally, wrote the chief surrealist André Breton, someone had given mad artists a “presentation worthy of their talents.”

Madness had never been so popular. But Heidelberg’s works were never less than controversial, and by the mid-1920s the link between art and madness had attracted the attention of the far right.

Adolf Hitler was, like Bühler, a self-taught artist. He was also, according to a psychologist who examined him in 1923, “a morbid psychopath … subject to hysteria”. After failing the entrance examination to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, he had made a living by copying tourist postcards in watercolor. When war broke out in 1914, he took his brushes and paints to the forehead, and when he entered politics after the war, he took his art with him.

Art helped him create a Nazi aesthetic, in the party emblems, badges and uniforms he designed, the sets he oversaw, and the propaganda he sponsored. Art also gave Hitler a higher political focus. Wars came and went, he liked to say, but in the millennia to come, Germans would be judged on their cultural achievements, just as great civilizations of the past were judged on theirs. To restore German culture was to restore “ethnically pure” German people; to see it decline was to attend the peoplethe decline. And the insane direction that contemporary art was taking marked, for him, a decline of epic proportions.

There is no evidence that Hitler read Prinzhorn’s book, but he would have been exposed to his ideas through newspapers and magazines, and this could very well have acted as a catalyst for his opinions. In my battle he rebels against the “idiots” and “scoundrels” who try to spoil the “healthy artistic feeling” of the great romantic painters he loves. The modernist “nonsense” and “obviously mad” stuff was a cynical ploy to avoid criticism from horrified fellow citizens, while movements such as Cubism and Dadaism were “the morbid outgrowths of mad degenerate men.” As early as 1920, the party’s manifesto called for combating “trends in the arts and letters which exert a disintegrating influence on the life of the people”. After 1933, that is what they did.

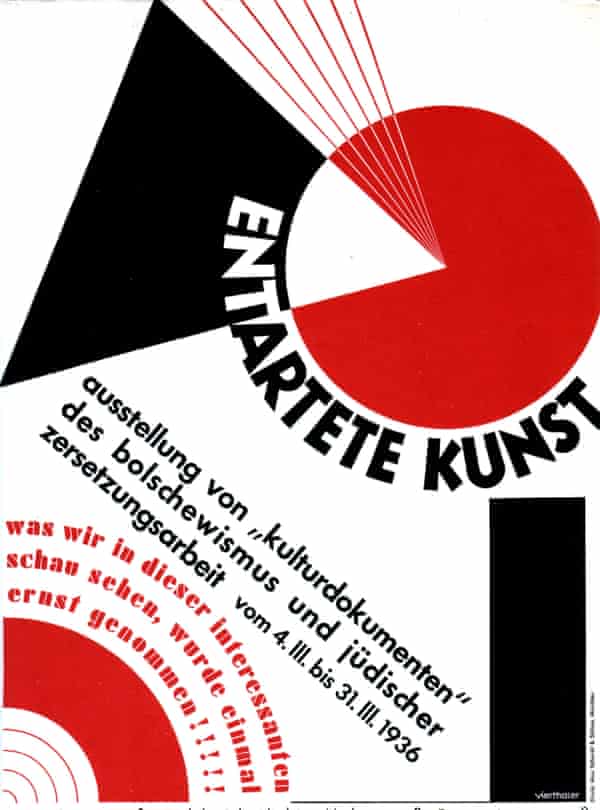

It was Goebbels’ idea, in 1937, to stage the Degenerate art show. With 3 million visitors, this traveling exhibition remains the most visited of all time, but it did not celebrate art; he put it in the pillory. From the return leg in Berlin, the propaganda department looted the Heidelberg clinic for more than 100 works, including several by Bühler, and presented a selection alongside professional art. The idea, as the official guide says, was to show that the avant-garde was even more “sick” than the real “mad”. This was presented as evidence of the great Judeo-Bolshevik conspiracy to undermine German culture and pollute the race with inferior blood. Cultural degeneration, the “slowly rotting world”, as Hitler said, foreshadowed biological degeneration, which hastened the Germans “to the abyss”.

The solution was simple: a “relentless war of cultural cleansing”. Modern art was withdrawn from German museums, to be sold or simply destroyed, and “degenerate” artists were driven out of the country. But Hitler’s most ambitious artistic project, his Gesamtkunstwerk, was to reshape the Germans themselves. To this end, in 1939 he ordered the first Nazi mass murder program, Aktion T4, targeting the mentally ill.

In 1940, Bühler was living in an asylum in Emmendingen, Baden-Württemberg. On March 5 of the same year, a small convoy of vehicles arrived at the establishment, made up of SS in civilian clothes. They loaded 50 patients on the buses, including Bühler, and took them to a specially adapted house for the disabled at Grafeneck Castle in Swabia. The patients were stripped and pushed into a gas chamber disguised as a shower room, and killed with carbon monoxide. This “euthanasia” action, as the Nazis called it, is widely regarded as a precursor to the Holocaust, and when it achieved its goals, many hardened Aktion T4 veterans were reassigned to camps in the United States. extermination in the east. By the end of the war, around 200,000 psychiatric patients would be killed by Hitler’s regime, including 30 artists from the Prinzhorn.

The war did not mark the end of the Prinzhorn collection. Miraculously, most of the works have survived and have inspired new generations of artists, including Jean Dubuffet, the creator of Art Brut (” Art Brut “). Bühler was assassinated, as were other artists of the Prinzhorn, but his achievements endure. They broadened the definition of art and widened the circle of authorized art creators beyond the elite.

Source link