[ad_1]

The night before Orthodox Christmas last month, Ethiopian priest Girmay Getahun donned a white robe and, Bible in hand, walked the dirt road to his church to prepare for services.

Around midnight, heavily armed fighters arrived in his village in the Benishangul-Gumuz region of western Ethiopia, sending Girmay to flee into the forest to hide for two days.

He returned to a gruesome sight: the corpses of his eight roommates, all day laborers on teff and peanut farms, who had become the latest victims in a series of gruesome and baffling attacks.

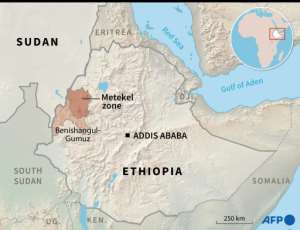

Map of Ethiopia locating Metekel area. By Simon MALFATTO (AFP)

Map of Ethiopia locating Metekel area. By Simon MALFATTO (AFP) Hundreds of people have died and tens of thousands have fled their homes.

The inter-ethnic violence in this lowland region, known as Metekel, predates a brutal three-month conflict further north that pitted Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed against the former ruling Tigray region party.

Still, the bloodshed has intensified as the military attempts to assert control over Tigray – highlighting how 2019 Nobel Peace Prize winner Abiy doesn’t have the luxury to tackle only one security crisis at a time.

In mid-November, 34 civilians were killed in Metekel when gunmen attacked a bus.

A camp in Chagni hosts people who have fled violence in the Metekel region. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP)

A camp in Chagni hosts people who have fled violence in the Metekel region. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP) At the end of December, a day after Abiy’s visit to the region, more than 200 people died in a pre-dawn massacre, some burned alive in their sleep.

And last month, more than 80 people died in a raid involving knives and arrows.

Even though analysts question who and what is behind the violence, there are fears that it will soon escalate.

Abiy’s government unveiled plans to form a militia of civilians displaced by past attacks to return to Metekel to “protect” those who remain.

In a camp for displaced people in the town of Chagni, east of Metekel, Girmay is one of the many residents who support this movement.

“I do not fully support the idea of forming a militia, because in my opinion it is like saying ‘kill each other’,” Girmay told AFP while clutching a wooden cross.

“But if there are no other options and if (the gunmen) are not disarmed, we will train recruits from here to protect our lives.”

‘We must defend ourselves’

Abiy has so far failed to explain the carnage in Metekel.

People fleeing violence in the Metekel area gather outside a tent where clothes are distributed at a camp in Chagni, Ethiopia. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP)

People fleeing violence in the Metekel area gather outside a tent where clothes are distributed at a camp in Chagni, Ethiopia. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP) He told lawmakers in October that the attackers were receiving training in neighboring Sudan, and in December he said the killings were aimed at siphoning off military forces sent to Tigray.

But his government has presented no evidence to support either claim.

At Chagni Camp, an ever-growing collection of tents crammed surrounded by water pear trees in Ethiopia’s Amhara region, theories center on long-standing conflicts over the land.

Most of the 20,000 residents of the camp are ethnic Amharas, Ethiopia’s second largest group.

Many support the idea of an “Amhara genocide” perpetrated by militiamen from the local population of Gumuz.

These fighters, they say, attack Amhara farmers like Girmay’s roommates to drive them from land they have long cultivated.

A displaced person sits among piles of clothing distributed at Chagni camp. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP)

A displaced person sits among piles of clothing distributed at Chagni camp. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP) Amhara officials are using this line to argue that Amhara’s security forces should be deployed en masse alongside the military to restore order.

“We have to stand up for ourselves. They won’t let us live,” Amhara official Asemahagn Aseres said, calling on Twitter for violent retaliation.

However, the reality is more complex, because the Amharas are not the only victims.

Recent high-profile massacres have killed and displaced the Agews, Shinasas and Oromos ethnic groups.

Civilians belonging to the Gumuz ethnic group are also on the run, with 34,000 people hiding in the forests for fear of violence, a local security official said last week, as quoted by media.

A water tap at Chagni camp. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP)

A water tap at Chagni camp. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP) Temesgen Gemechu, an Oromo lawyer from Metekel who has researched the violence, showed AFP a list of 262 Gumuz who he said had died in attacks dating back to 2019.

Their suffering goes unnoticed, he said, because the Gumuz – a small group historically subjected to slavery – have limited political power.

“When the Oromo die, everyone talks about it. And for the Amharas, it is the same. But nothing happens when the Gumuz die, ”he said. “Who cares about them?”

Greedy recruits

The violence left civilians in Chagni visibly shaken, said a psychiatrist from the health ministry stationed there.

“Everyone here is somehow traumatized,” he said.

“A lot of people suffer from PTSD, high anxiety, and are very aggressive because they’ve seen people get butchered.”

Dawud Kibret shows scars from where he was hit in the abdomen. He wants to join a militia organized by the government. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP)

Dawud Kibret shows scars from where he was hit in the abdomen. He wants to join a militia organized by the government. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP) Conditions in the “miserable” camp are not helping, admitted Tilahun Anbelu, an Amhara government official who helps manage it.

One recent morning, women selling coffee and shiro stew crouched in front of poorly pitched tents that had been blown over by the wind.

Outside another tent, a Unicef employee used a microphone to announce that residents would soon face fines of 10 Ethiopian birr (about 25 US cents) if they continued to relieve themselves in the areas. bushes around the camp rather than in the newly constructed latrines.

Standing nearby, Dawud Kibret, 38, said he was desperate to return to Metekel and did not hesitate to join the government-organized militia.

“I want to give up my job to protect my people,” said Dawud, a farmer who fled Metekel after saying a fighter from Gumuz shot him in the abdomen.

“I want to serve people like a soldier.”

He is on the right track to make his wish come true.

Over the weekend, Lt. Gen. Asrat Denero, head of security at Metekel, told state media that around 10,000 militia recruits had been identified.

The training, he added, would start “soon”.

Source link