[ad_1]

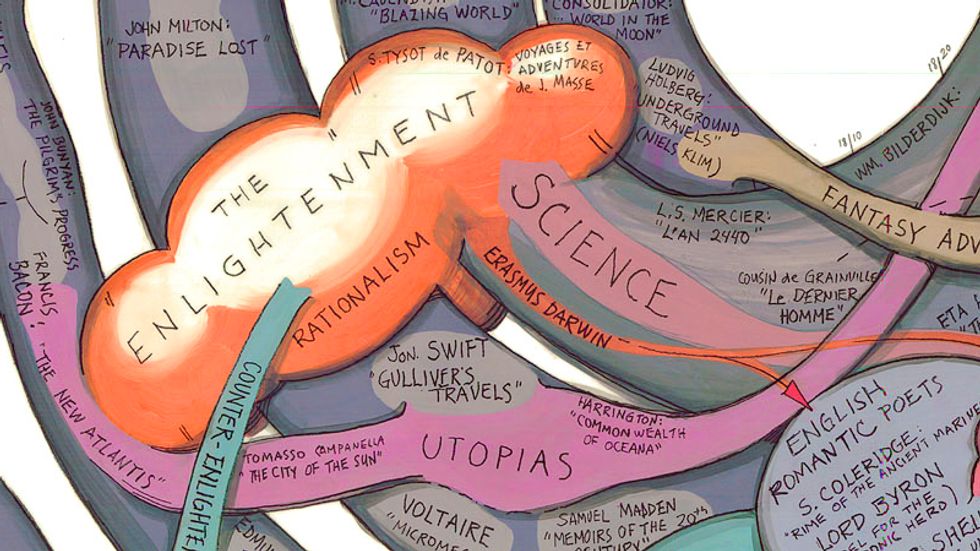

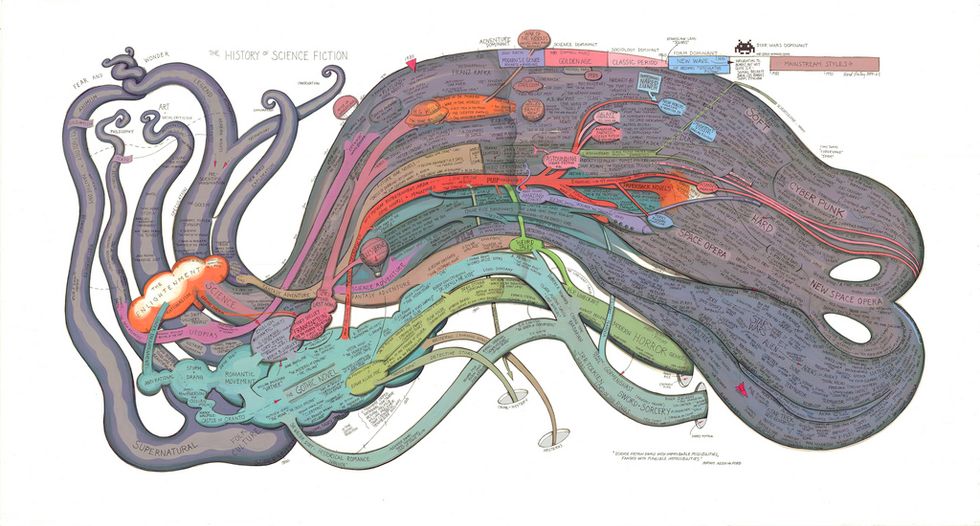

Is it the image of a whale, as the empty eye sockets on the right suggest, or of a giant squid, its tentacles waving to the left? It’s neither, but the image of a sea monster may be appropriate, as mysterious creatures from the depths – Moby Dick, Nessie, the Nautilus – affect more than tangentially this diagram. This is what this image, on closer inspection, appears to be. And much more: it is also a work of art and a chronology; a literary checklist and historiography of a particular genre. There are probably other things too, but above all it is a map, known and unknown places, and the connections between them.

Entitled A story of science fiction, this map is the work of Ward Shelley, a sculptor, performer and painter based in Brooklyn (1). One of his specialties in the latter discipline is the enormous timeline diagrams, including an Extra Large Fluxus Diagram and a very illuminating Autobiography (2). It traces, from left to right, the origins and evolution of a whole genre of popular fiction – science fiction.

A short and precise definition of a genre as broad as SF isn’t easy, although the litmus test to distinguish it from its conjugal twin, fantasy, cited on Shelley’s diagram, is helpful: Science fiction deals with improbable possibilities, fantasy with plausible impossibilities. Simply put: if he has elves, that’s fantasy. If there are aliens, it’s SF.

One thing to keep in mind: No matter how far into the future (3) it is, SF is still a critique of the time in which it was produced. Once that gets in, you’re less likely to be annoyed with the flared pants spacesuits in Seventies SF. Then as now, some of the main themes of the genre revolve around the exploration of deep space, contact with alien species, advances in robotics and computing and human engineering. of the space-time continuum.

But we are – perhaps true to the genre – ahead of ourselves. Let’s take a look at this map from its curly tentacle beginnings: the fear and wonder that have been humanity’s nocturnal companions since the invention of the campfire story.

Some ancient channels of pre-SF literature include philosophy (Plato Republic), mythology (the Anglo-Saxons Beowulf), the pre-scientific imagination (the Golem of medieval Jewish traditions), exploration of the New World (Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe) and art (Thomas More’s Utopia). These latter two works could just as easily have been categorized into each other, which reveals the flip side of Mr. Shelley’s obsessively detailed work: his classifications are extremely questionable. That is of course part of the fun of this card.

SF remains a twinkle in the eye of the speculative fiction writer until two great literary traditions collide, or merge: Enlightenment (providing the piece of science) and Romanticism (providing the piece of fiction). This would ultimately lead to SF, while also cradling Gothic novel, modern versions of folk and fairy tales, and other genres, some (4) spilling into chasms towards, one suspects, elaborate diagrams of theirs. clean.

The years leading up to 1900 produced classic works of early science fiction such as Mary Shelley Frankenstein, or LS Mercier’s Year 2440. He also saw three prolific and iconic writers, each contributing to the rapidly growing field of SF: Jules Verne, HG Wells and EA Poe. After 1900, the genre exploded into a heavy clutter of subgenres, dominated by a plethora of influential magazines with titles like Strange tales and Astonishing.

A generalized chronology distinguishes the periods dominated by adventure (the era of “ rockets and ray guns ” after 1920), science (“ the golden age ” of SF, after 1940), sociology (the ‘classical period’, after 1950), form (a ‘new wave’, after 1960) and Star Wars (SF turns into Mainstream Styles, after 1980). Some influential genres are mentioned, such as Space Opera, SF “Soft” and “Hard” and Cyberpunk. The rest of the diagram is packed with hundreds of books – and movies – depicting the widest variety of stories imaginable, thus providing even the semi-interested SF reader with a handy map of vast areas yet to be explored.

Many thanks to Nick Andert, JB Post, Jeff Cupp, Stannous Flouride, Sue Somers and Toon Wassenberg for submitting this card, a winning entry to the annual Best Science Cards competition, hosted by Places & Spaces. Learn more about this competition, and an overview of the other cards, here.

Strange Cards # 506

Do you have a strange card? Let me know at [email protected]

(1) See bigger (and bigger) at Mr. Shelley’s own website.

(2) Here and here.

(3) Typically either a future in which science has made enormous progress (towards utopia), or, more frequently in recent years, society has collapsed (into dystopia). Strictly speaking, these evolutions do not need to take place in the future, but can also occur in alternate realities, whether past or present.

(4) horror, westerns, crime / mystery, fantasy.

Source link