[ad_1]

Dawn Elrick had only been working as a runner in the TV industry for a few months when two assistant producers told him they would like to spit it. She was 22 years old. She didn’t know what spit roasting meant, so that night she Google searched for it. “When I realized what they said,” says Elrick, who is now 43 and works as a producer in Glasgow, “I felt so horrible.” She was afraid of having to go back to work the next day.

A few years later, Elrick was working on an entertainment show. A presenter was pulling him in for bear hugs, grabbing his buttocks as he did. On the closing night, he cornered her. “He said he wanted to come in my face,” Elrick recalls. She didn’t feel that she could complain to her superiors. “It was such a busy production,” she says. “Everyone was trying so hard to get out of this… No one had the space to face it.”

A few years later, the Jimmy Savile story had just erupted, highlighting the issue of inappropriate behavior in the workplace. Elrick decided to file a historic complaint against the TV presenter. “They said I would be told if he was in the building,” she said. ” This does not happen.

Elrick had largely rationalized these incidents as the grim cost of the job she had dreamed of since she was a teenager. “It’s so standardized that you think it’s part of your job and you have to put up with it,” she says. “But it has never been easy with me.” However, something happened that made him change his mind: In April 2021, the Guardian revealed the story of multiple bullying and sexual misconduct charges against Noel Clarke, which he denied, and 2,000 people signed an open letter, calling for an end to rampant harassment, intimidation and sexual abuse in the UK film and television industry.

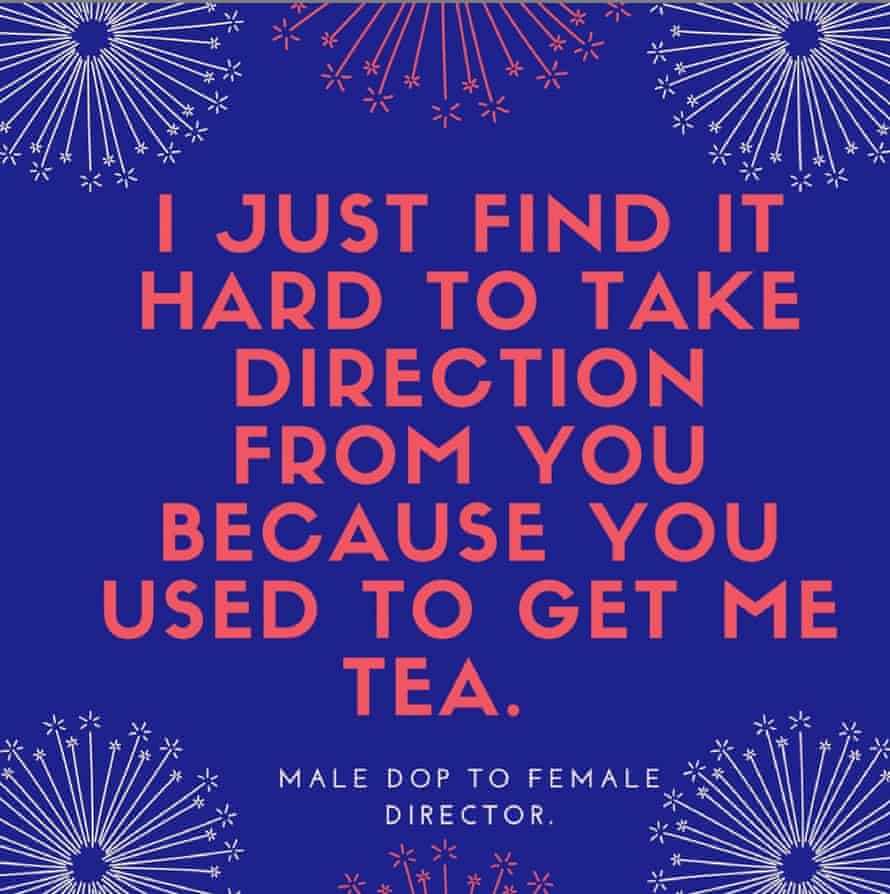

Suddenly, change seemed possible. “I thought to myself that so many women have signed this open letter and they must all have a story to tell,” Elrick says. “I was angry and I was fed up. She created an Instagram account, Shit Men in TV Have Said to Me, and wrote the first posts herself, based on her experiences of harassment on TV sets, before sending it to a few friends in confidence. “I thought about putting in a few stories,” she says, “and leaving them for a week or two. But the submissions started to come in en masse and quickly.

In just four months, the story has become a must-read. Hundreds of anonymous submissions detail what it is like to be a woman in the UK film and television industry. They range from disparaging and sexually explicit remarks and disparaged and dismissed professional accomplishments to, in extreme cases, sexual assault.

“Who did you blow a pipe to to reach such a high position?” Quotes one account. Another details the story of a woman locked in a room by a male producer at a party, who insisted on giving her a massage. “I had to fight to get out of the room,” she says, “and I told him I would scream and bite his arm if he didn’t let me go.” “My cock throbs sitting so close to you,” said another, quoting the words of an experienced male director. Another man told a colleague to come back to his hotel room because he was “no longer a rapist.” And besides, you’re unstoppable anyway. In one production, the scene of a rape scene was nicknamed “the Weinstein Room” by the directors.

Elrick was overwhelmed by the sheer volume of submissions. “My goal is to go back through the catalog of messages,” she says. “There are about 300 messages in place now, and I have another 100 to get through. And it is with me that I publish a lot. Elrick aims to repost most of the messages she’s sent, but she eliminates stories that can be triggered and she doesn’t name those accused of abuse.

She does not attempt to verify the veracity of the accounts sent to her, but argues that the sheer volume of responses, coupled with repeated patterns of similar behavior, make them plausible. “Because we don’t give out names and everything is anonymous, I don’t see why anyone would lie,” Elrick explains. “And my presumption is that, for the most part, women don’t lie about these things.”

She found the community that has formed around the Instagram account to be unexpectedly moving, providing women with “a safe and cathartic space where they can share their experiences.” And, during Covid, the account took on the role that could once have been served by informal whisper networks in person. “In 2021, these are stories we might have told ourselves in the pub,” she says. “But the women don’t have the space to talk to each other because we all work from home.”

Plus, the account provides a “visual record of a struggling industry,” says Elrick. “I now realize that it is very important that these accounts are read and listened to, and that the industry can understand how far and how far the problem goes. Since Clarke’s story first broke, leading organizations have expressed a desire to improve working conditions for women in the industry. Bafta and the BFI recently announced new efforts to tackle bullying, harassment and racism in the workplace, while the Film and TV charity launched a new bullying support service.

But these measures, while well-intentioned, are probably not enough to change an industry with worrying behaviors, unless production managers have a sincere desire to change. Elrick hopes senior industry officials read the posts, understand how prolific abuses of power are, and take the appropriate steps to improve conditions on their sets. “It’s important for people to know how women feel in the industry,” she says. “How vulnerable they feel. How angry they feel. Industry could use it as a litmus test of how its corporate culture affects 50% of its workforce. I am eager to be a part of the solution in every way that I can be.

In the UK, Rape Crisis offers rape and sexual abuse assistance on 0808 802 9999 in England and Wales, 0808 801 0302 in Scotland and 0800 0246 991 in Northern Ireland. In the United States, Rainn offers assistance at 800-656-4673. In Australia, support is available at 1800Respect (1800 737 732). Other international hotlines are available at ibiblio.org/rcip/internl.html.

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or by emailing [email protected] or [email protected]. In the United States, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the Lifeline crisis helpline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines are available at befrienders.org.

[ad_2]

Source link