[ad_1]

Before Kennedy became president in 1961, his country had made little attempt to understand the rapid changes in Africa.

By the time of his assassination in 1963, the situation had radically changed.

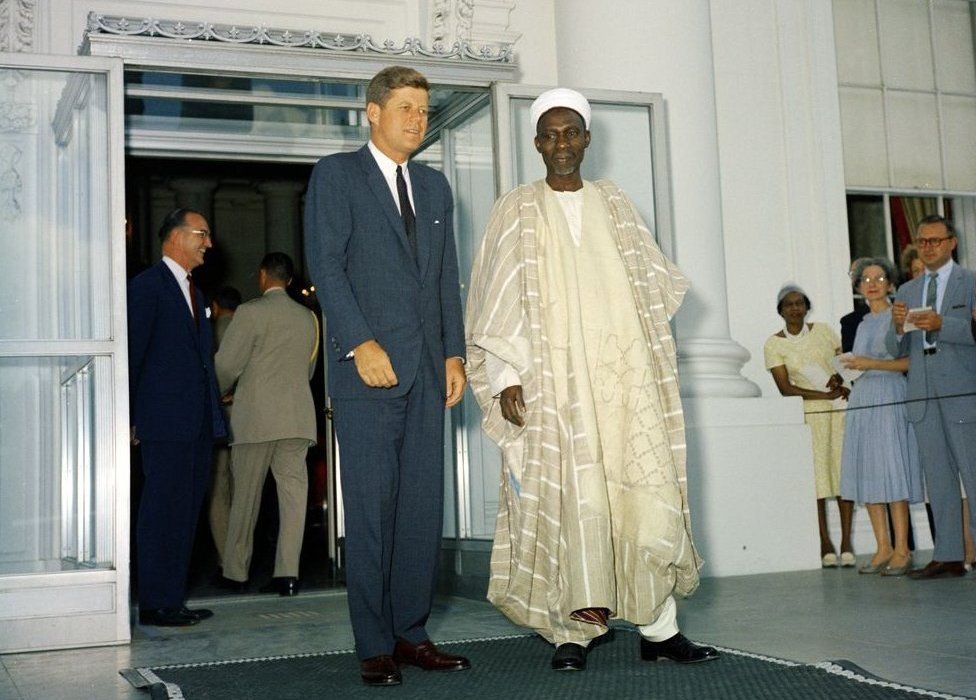

During his brief tenure, Kennedy had received in the White House either the head of each independent African state – numbering more than two dozen at the time – or his ambassador.

Senegalese President Léopold Sédar Senghor, a key figure in the anti-colonial movement in French-speaking countries, flew to Washington in November 1961

A year before he became president, 17 African countries had gained independence from their colonial masters, and aware that the world was changing, Kennedy knew that a new relationship had to be forged.

This relationship was based on the support of the new African nations.

It was a foreign policy perspective that essentially survived, given the occasional adjustments, until President Donald Trump’s efforts to replace it with his more transactional approach.

It has been reported that Mr. Trump has infamously used derogatory language when speaking of the continent, and Kennedy’s predecessor, Dwight D. Eisenhower, had his own negative views.

He told Togo’s President Sylvanus Olympio that the reason the United States shared an ambassador between Togo and Cameroon was because he did not want his diplomats “to have to live in tents.”

During the 1960 election campaign, Kennedy repeatedly criticized the Eisenhower administration for “neglecting the needs and aspirations of the African people” and stressed that the United States should be on the side of anti-colonialism and self-determination, not on the side of the colonialists.

Once in office, Kennedy invited African leaders on state visits and laid out the red carpet.

Accompanied by First Lady Jackie Kennedy, he would greet each of them – including Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie and King Hassan IV of Morocco – upon their arrival in the country.

There were also honor guards, lavish dinners, and visits to the ballet, theater, and places of historical interest.

The visits were all highlighted in the media and the public was encouraged to come out and cheer.

Kennedy and his guests would be driven through streets adorned with welcoming banners and enthusiastic crowds and, weather permitting, in an open-top car.

Of course, there was an element of realpolitik in all of this. The Soviet Union was making similar overtures to African states seeking to distance themselves from the old colonial masters.

Upon taking office, Kennedy knew he had to act quickly to befriend emerging African countries.

In the Oval Office, he told the National Association of Clubs of Women of Color: “I believe… if we live by the ideals of our own revolution, then the course of the African revolution in the next decade will be towards the end. democracy and freedom and not towards communism and what could be a much more serious type of colonialism.

A month after his inauguration, he asked Vice-President Lyndon B. Johnson to travel to Senegal to meet with President Léopold Sédar Senghor, whom he considered a key ally in trying to rally French-speaking countries.

Then a month later Kennedy launched the Peace Corps – which sent young Americans around the world – and in August 1961 invited the first group of volunteers to the White House to prepare to travel to Ghana and Tanganyika. .

The assassination of the hero of Congolese independence, Patrice Lumumba, with an alleged CIA involvement, three days before Kennedy took office, reminds us that the battles of the Cold War with the Soviet Union were also fought on the continent.

But I would say Kennedy was genuinely interested in the development and advancement of the continent. African leaders who fought hard for independence were not naive and took Kennedy at his word: that the relationship could be mutually beneficial.

His untimely death was deeply felt in Africa – especially as his successor, Johnson, did not share his drive to cement relations.

Now, 60 years later, President Joe Biden is beginning to shape his policy towards Africa.

In a statement earlier this month, he said the United States stands ready to be “Africa’s partner, in solidarity, support and mutual respect.”

Biden’s words echoed Kennedy’s pledge – now we’re waiting to see if the actions match the rhetoric.

Source link