[ad_1]

The presence of Mycoplasma salivarium in the lower respiratory tract of ventilated patients with COVID-19 infection is associated with an increased likelihood of dying. The result was part of a molecular investigation that examined how the microenvironments of the airways affected severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2).

Leopoldo N. Segal and colleagues suggest that lung microbes could be predictive of severe COVID infection and antibody resistance.

“These data highlight the importance of the abundance of SARS-CoV-2 in the lower respiratory tract as a predictor of mortality, and the significant contribution of the host cell transcriptome, which reflects the response of cells to lower respiratory tract infection, ”the researchers wrote.

The results could help identify patients most at risk for poor clinical outcomes and suggest alternative treatments early on.

The study “Microbial signatures in the lower respiratory tract of mechanically ventilated COVID19 patients associated with poor clinical outcomes” is available for preprint on the medRxiv* server, while the article is subject to peer review.

Classify microbial signatures

Lower respiratory tract samples collected from ventilated patients following COVID-19 infection during the first wave in New York City. They collected respiratory tract samples from 142 patients with COVID-19 infection.

Mycoplasma salivarium in the respiratory tract is linked to poorer clinical outcomes

Using metagenomics, researchers linked microbes living in the lung microbiome to patients’ clinical outcomes.

The results showed that high amounts of Mycoplasma salivarium was associated with a higher viral load of SARS-CoV-2. In addition, a limited immunoglobulin response in the lower respiratory tract was correlated with an increased risk of mortality.

“The data presented here through the use of direct quantitative methods (RT-PCR) and an untargeted semi-quantitative approach (metatranscriptome sequencing) support the hypothesis that the SARS-CoV-2 viral load in the pathways respiratory tract plays a critical role in the clinical progression of critically ill COVID-19 patients, ”the researchers wrote.

No evidence of poorer clinical outcomes from co-infection with respiratory pathogens

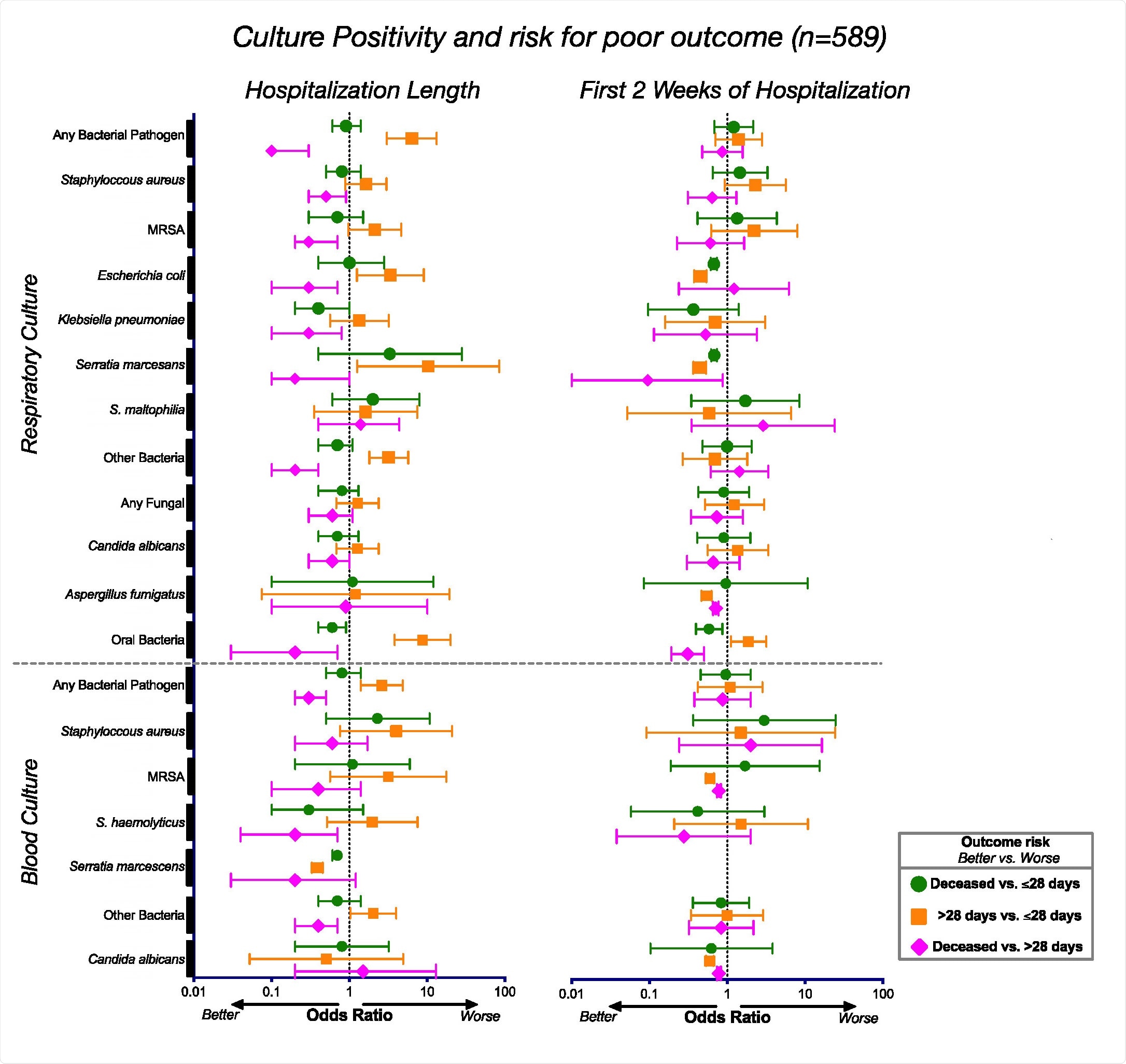

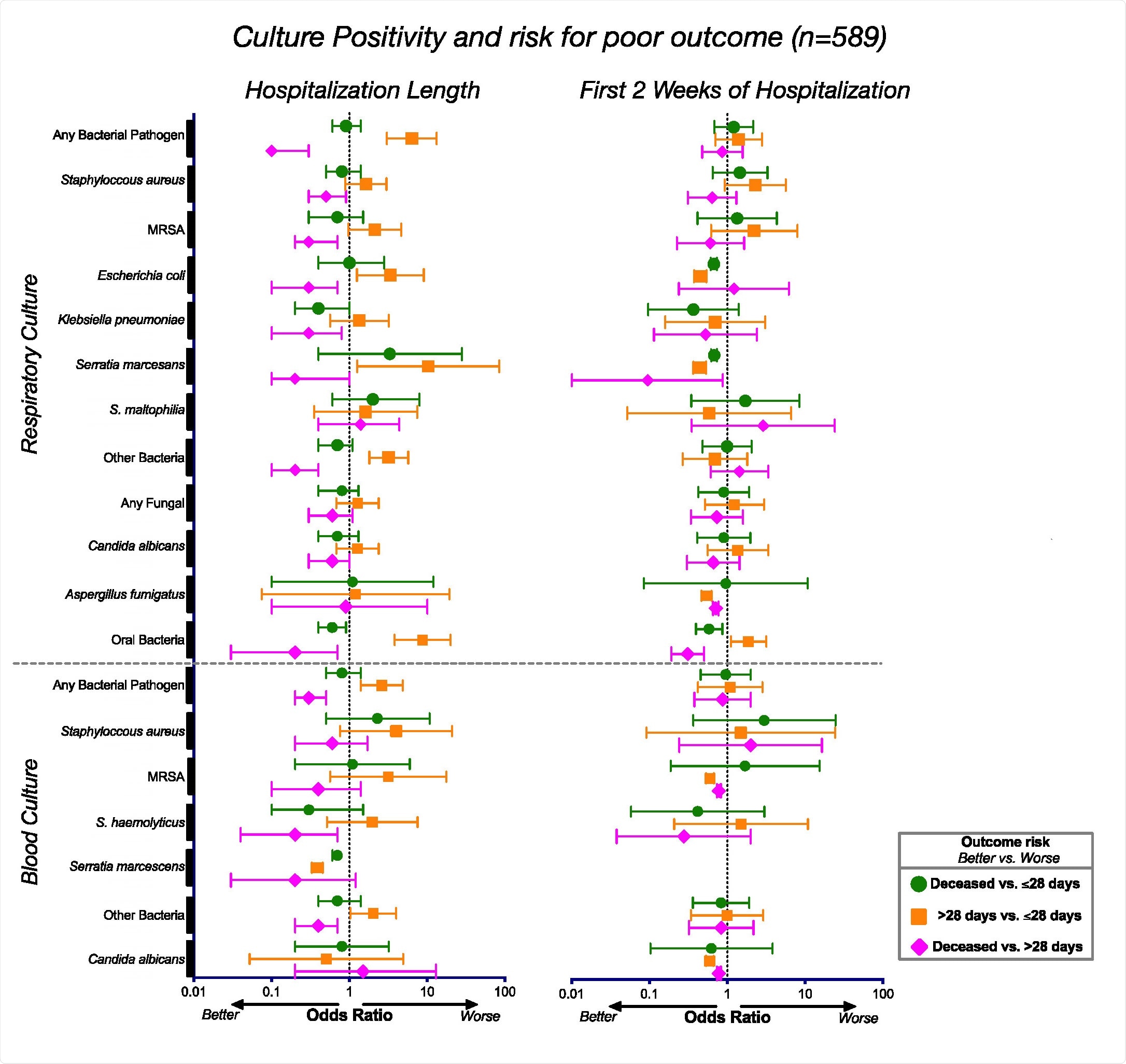

While most patients received antibiotics and broad-spectrum antifungals, there was no evidence of worsening effects of coinfection with bacterial, viral, and fungal respiratory pathogens.

To examine the risk of death from COVID-19 infection, the team analyzed laboratory cultures from 589 patients hospitalized with respiratory failure due to severe COVID-19 infection.

The results showed that patients with poor clinical outcomes did not succumb to other respiratory infections. There was also no link between positive microbial cultures and mortality in severe COVID-19 infections.

Associations between culture positivity and clinical outcomes. Odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for the culture positivity rates for the entire cohort (n = 589) during the duration of their hospitalization (left) and during the first 2 weeks of hospitalization ( to the right).

Bacterial changes seen in patients ventilated for more than 28 days

Beyond microbes, the lower respiratory tract showed a strong presence of SARS-CoV-2, which was associated with death. A small sample of patients had influenza A or B viruses, which suggests that the flu is unlikely to have occurred simultaneously with a coronavirus infection.

When observing bacteria in the lower respiratory tract, metatranscriptome data found phages actively present. The researchers suggest this could be evidence that alternations in the bacterial microbiome could occur in patients with severe COVID-19 infection.

Changes have been observed in Staphylococcus phages, and Mycoplasma salivarium was actively present in patients requiring ventilation for more than 28 days and patients who died compared to patients ventilated for less than 28 days.

Microbial impact on the immune response

Patients with poor clinical outcomes expressed pathways that activated genes related to degradation, transport, as well as expression of antimicrobial resistance and signaling genes.

The researchers write:

“These differences may indicate important functional differences leading to a different metabolic environment in the lower respiratory tract that could impact host immune responses. It could also be representative of differences in microbial pressure in patients with loads. higher virals and different inflammatory environments. “

There was also upregulation in the Sirtuin and Ferroptosis signaling pathways in the most severely ill COVID-19 cases. This coincided with features of an inactivated immune response, including phagocytes, neutrophils, granulocytes, and leukocytes. Downregulation of immunoglobulin expression levels and mitochondrial dysfunction have also been observed.

Based on the data, the team suggests that the lungs of critically ill patients who require ventilation following COVID-19 infection express an imbalanced state rather than elevated inflammation. This seems to predict a worsening of the prognoses.

Further analysis revealed differences associated with survival in responses to interferon. Activation of type I interferon was a predictor of increased mortality.

“While additional longitudinal data will be needed to clarify the role of interferon signaling on disease, the data presented here suggests that the combination of microbial and host signatures could help understand the increased risk of mortality in patients with the disease. seriously ill COVID-19. “

*Important Notice

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports which are not peer reviewed and, therefore, should not be considered conclusive, guide clinical practice / health-related behaviors, or treated as established information.

Source link