[ad_1]

IIt’s 1940, and a five-year-old boy is lying in an oxygen tent. He struggles to breathe and hallucinates that his toy soldiers are alive and walking into the room, the monster with their bayonets.

He suffers from diphtheria, a disease also known as Strangler Angel. There is a vaccine, but not all children have been vaccinated. The bacterial infection creates a membrane at the back of the throat, cutting off the air supply.

The little boy’s mother, who was desperately watching by the oxygen tent, saw diphtheria taking away other children.

He will ultimately not take his son. The membrane will fail to completely close his airways and he will come out of the oxygen tent. He will attend the funerals of classmates who died of diphtheria and polio. He will eventually run alongside his friend, an athlete born blind after his mother contracted rubella during pregnancy. He will shake a rock in a box to guide his friend to the finish line.

Throughout his schooling, children he knows will die of illness.

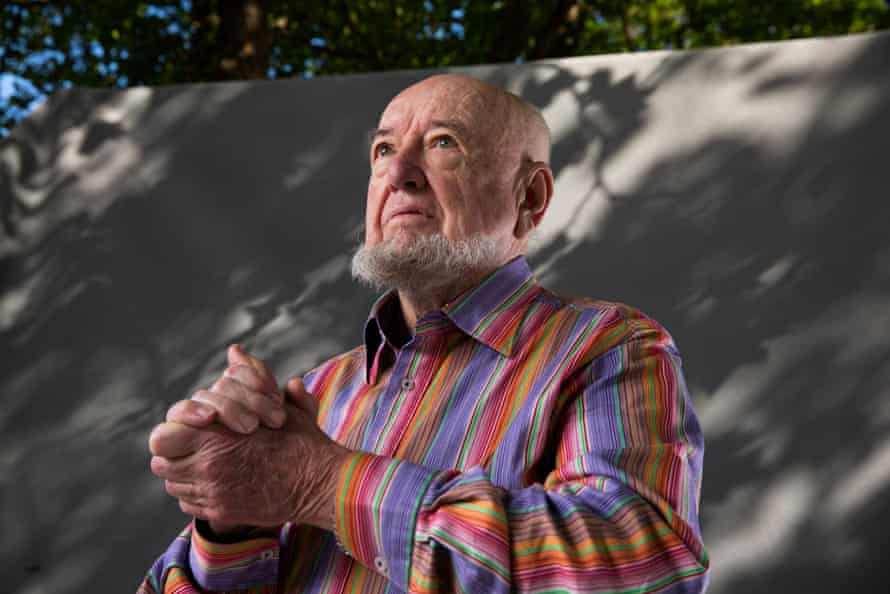

He will survive, luckily. He is still alive now, at the age of 85. He’s my dad, and his name is Tom Keneally.

“One of the brothers (the Christian brothers at St Patrick’s College in Strathfield, Sydney) would come into the classroom every now and then and tell us that someone was dead,” Keneally said. “We would say ten rosaries for them, and the brother would say that God takes the best children, and I would be relieved not to be one of those.

“It didn’t sound like a pervasive threat as children because we just lived our lives, although I think for our parents it was always there, that possibility.”

Shortly after birth, Australian children are vaccinated against hepatitis B. Between six weeks and 18 months, they are vaccinated against various diseases, including diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, pneumococcal disease, meningococcal disease, measles, mumps, rubella, polio, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), rotavirus and chickenpox (chickenpox).

Some vaccines can also protect against certain cancers later in life. As Professor Raina MacIntyre, head of the Biosafety Research Program at the Kirby Institute and Professor of Global Biosafety at the University of NSW, points out, the hepatitis B vaccine protects against liver cancer, while the hepatitis B vaccine protects against liver cancer. Human papillomavirus vaccine protects against cancer of the cervix and penis.

“People don’t remember the gains we made,” says McIntyre.

“In the 19th century, the main cause of death in children was infectious diseases. People would have 10 children and could lose five. We were living with high rates of infant mortality, ”she said.

In addition to two world wars, Australians in the first half of the 20th century had to contend with a Spanish influenza pandemic and an outbreak of bubonic plague, as well as numerous one-off fires of disease.

The deadly diseases that regularly plague the population – such as suffocating diphtheria, crippling polio, devastating tetanus – have made childhood precarious.

One in 30 children died of gastroenteritis, diphtheria, scarlet fever, whooping cough and measles in 1911. In 1907, infectious diseases killed more than 300 in 100,000 people, according to data from the Australian Institute of Health and Medicine. well-being. By 2019, that number had fallen to around 10.

For modern parents, the names of diseases like polio, smallpox, and diphtheria have been relegated by vaccination to obscure words of no practical relevance. But while these cruel diseases no longer kill Australian children, experts say there may be a risk of falling into complacency.

“The visibility of the ravages of polio and the fact that most people knew that someone who had had a child died were really powerful engines, people were desperate for vaccines,” says David Isaacs, clinical professor in pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Sydney, and author of Defeating the Ministers of Death – The Compelling History of Immunization. “A lot of young people now have no idea how horrible it was.”

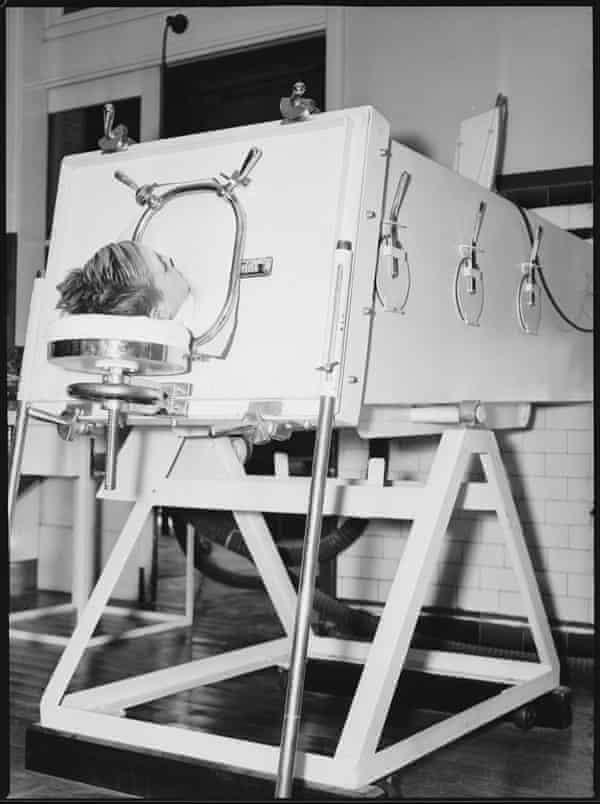

Tom Keneally’s diphtheria infection was not to be his last childhood in hospital. In 1944, he was recovering from pneumonia near a boy in an iron lung, suffering from polio. The boy was studying for the Leaving Certificate, the precursor to HSC.

“He had a stand over his head that the textbooks could be slipped into, and I remember he was studying Hamlet,” Keneally says. “His mother was always there, turning the pages and changing the books, and that’s how he studied.

Some time later, he learned that the boy was dead when a power cut rendered his steel lung unusable.

Dr Peter Hobbins, a medical historian at the Australian National Maritime Museum, says polio was still killing children in the 1950s.

“It was a fact of life in Australia. Many people do not realize how many diseases were rampant until relatively recently. There is reduced visibility of the consequences of these diseases, people do not appreciate the fear of parents to send a child to school and not see him return to the family, ”he said.

“Fortunately, we are not seeing new cases of polio, but there are still people living with the consequences of the disease and they feel forgotten. “

Not that there weren’t any triumphs, including the eradication of smallpox, which Isaacs said killed up to one in three babies in 18th and early 19th century London. A campaign by the World Health Organization, launched in 1967, wiped it out in 1980.

The first smallpox vaccines in Australia were given in the early 1800s. It was not good for the people of the Eora Nation. In 1789, a disease believed to be smallpox was introduced by the settlers. It ravaged Sydney’s Aboriginal population, killing up to 70%.

While smallpox is no longer a threat, MacIntyre warns that diseases we have almost forgotten can easily reappear if vaccination rates decline.

“One example is the fall of the Soviet Union,” she said. “There were good vaccination programs, then when the Soviet Union fell, many ceased to be conducted.”

As a result, cases of diphtheria, which were almost unknown due to vaccination, reached 140,000 and the disease killed 4,000 children and young adults.

“If we stopped vaccinating against diphtheria here, we would see the same thing,” MacIntyre says.

Despite their life-saving properties, vaccines have often been greeted with suspicion. Hobbins says a tragedy in 1928 impacted diphtheria vaccination rates – but it may also ultimately have increased vaccine safety.

“It became known as the Bundaberg tragedy, or the serum tragedy. A batch of diphtheria vaccine contaminated with Staphylococcus aureus was injected in large doses to 20 children, and 12 died, ”he says.

“A diphtheria epidemic could potentially kill 12 out of 20 children, but this event delayed the course of vaccination by several years. But one of the consequences of the tragedy was an increase in manufacturing and quality testing standards, which significantly reduced the risk of vaccine contamination. “

Although vaccination warrants are sometimes invoked to counter vaccine reluctance, they can backfire. In Defeating the Ministers of Death, Isaacs speaks of 80,000 strong protests in the British city of Leicester at the end of the 19th century, in response to a mandate to vaccinate against smallpox.

“I really believe in negotiation and respecting people’s intelligence, because reluctance to vaccinate is not a question of intelligence. A lot of hesitation is based on fear and misunderstanding, and we don’t want to alienate people, ”he says.

“Then you can sometimes bring people around if you’ve developed a close relationship, which is why I strongly believe in using GPs to get these messages across. “

Still, Australians are very supportive of vaccinating children, he says.

“Our routine childhood immunization rate is around 95%. This is enough to give you herd immunity, so that there is no endemic spread of measles. “

MacIntyre agrees.

“Australia has had high vaccination rates. Anti-vaccines are around 2%, which is not that much, ”she said.

“It is not so much a reluctance to vaccinate as a vaccine confusion [with Covid-19 vaccines]. I believe we can achieve good vaccination rates [against Covid-19] in Australia.”

As for the committed anti-vaxxers, Tom Keneally knows what he would like to do to try and change their perspective.

“I would like to take anti-vaccines back in time to my childhood. There would be a story in every street that could change their mind.

Source link