[ad_1]

Last month, Emmanuel Macron trumpeted a new electric battery factory for the former coal mining region of northern France. Only problem: the local politician and presidential candidate Xavier Bertrand had already made the announcement three days earlier.

In what amounted to his first re-election campaign speech, Macron then highlighted the need for France to “reindustrialize” and said he hoped electric battery projects in Hauts-de-France heralded “ massive investments in the transformation of the automotive industry ”.

“It is not the speeches that count, the real question is to know what is really done,” commented Bertrand, former center-right Minister of Health who has headed the regional council since 2015.

Less than a year from the presidential elections, the political standoff Hauts-de-France reflects how the issue of reindustrialisation has taken center stage in the countryside, as the region becomes a test for the rehabilitation of mainstream politics.

Marine Le Pen’s far-right party has found fertile ground in the once left-wing province, which has France’s highest unemployment rate at 9.4%. the National Gathering The leader, whose opinion polls suggest she will garner enough votes to make it to the second round of presidential elections next spring, recorded some of her biggest electoral victories there.

Hauts-de-France is an obvious choice for battery projects. The French automobile industry invested heavily in it from the end of the 1960s, which partially offset the decline in mines and steel. But manufacturing has increasingly been outsourced to cheaper factories in emerging markets and jobs have leaked. Now that automakers face antitrust scrutiny and EU emissions regulations, factories are under threat again.

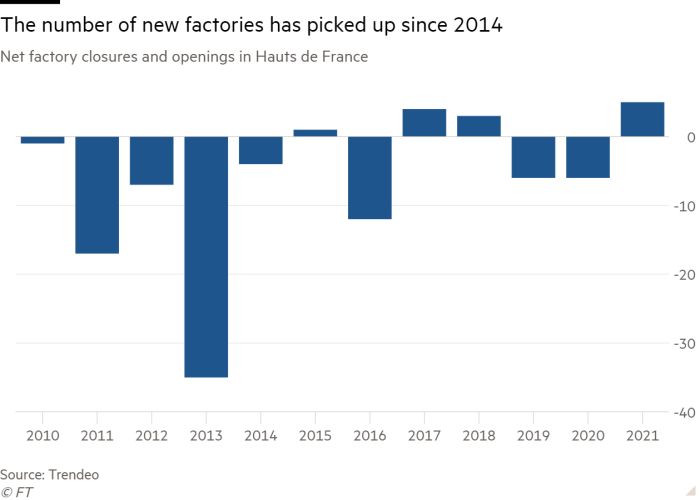

The northern region around Lille has recorded the second highest number of net factory closures in the past 12 years among French regions, according to data compiled by Trendeo, a Paris-based consulting firm. Between 2006 and 2016, the region’s industrial sector lost more than a quarter of its workforce, the largest drop recorded in metropolitan France, said Insee, the French statistical agency.

But there are tentative signs of improvement: Factory closures have slowed over the past three years. Hauts-de-France has also been among the top destinations for foreign direct investment since 2014, and has the highest number of jobs created per capita by FDI, according to Business France, a government agency.

Analysts say that while Macron’s presidency and Bertrand’s local efforts have yet to reverse the region’s industrial decline, the rise of the far-right in the poorest province and the emergence of the yellow vests the protests made it the subject of greater financial and political attention.

At the head of a highly centralized administration, Macron deserved most of the credit for injecting money into new industries, notably batteries and hydrogen, by cutting red tape and “begging the EU” to take industrial autonomy more seriously, said Elie Cohen, senior economist. at the National Center for Scientific Research.

Its efforts to bring production back to France gained popularity during the pandemic, as logistics and supply issues emerged in industries such as drugs, medical equipment, and manufacturing components, including semi-trailers. conductors.

These efforts were supplemented by funding and training provided by the regional council chaired by Bertrand. He “got his hands dirty” while fighting to attract businesses and give them autonomy once they arrived, according to Jean-Luis Guérin, economist and director of Finorpa, a local private equity firm.

In the city of Douvrin, in the north of the country, an electric battery joint venture between the automaker Stellantis and the French energy group Total, called Automotives Cell Company (ACC), is due to start producing batteries at the end of 2023, thus creating 1,400 to 2,000 jobs by 2030. The State and the region have invested 1.2 billion euros and 120 million euros respectively, according to Yann Vincent, managing director of the joint venture.

Batteries for electric vehicles have become a state priority because Europe “cannot be in the hands of China,” which currently dominates the market, said Vincent.

Whatever gains are made, the turnaround is fragile, say economists. They indicate a drop in net foreign direct investment in France during last year’s pandemic. Some argue that this should prompt a rethinking of France’s centralized policy.

The country’s “top-down” strategy of pumping money into big companies like Stellantis has not done enough to help small businesses grow, said Daniela Ordonez, of Oxford Economics. France has been “too paternalistic” in the way it chooses which industries to support.

“Trade in industrial products is deteriorating every month, our market share in world exports is deteriorating every quarter,” said Patrick Artus, chief economist at Natixis. “If you continue to create only bad jobs, even if you reduce unemployment, you will have more yellow vests. “

Meanwhile, for Fabrice Jamart, 40, member of the CGT union at the Stellantis factory, talking about state policy and new industries escapes the more immediate risks of job losses. Looking out the window of his makeshift office outside the factory, he said, “Hope is good, but hope doesn’t put food in my fridge.”

Source link