[ad_1]

According to a study published Tuesday, unusual state regulation dictating how doctors should treat a specific disease seems to be paying off in New York.

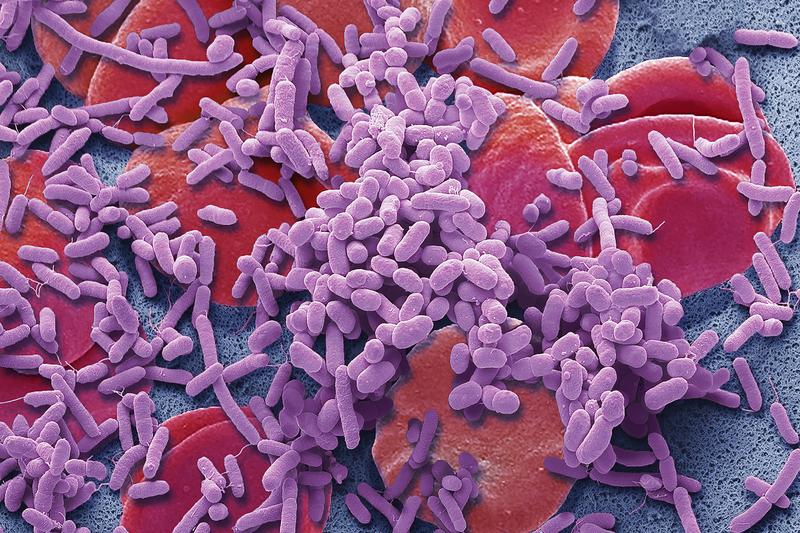

The disease is sepsis, which is the most common cause of death in hospitals. And the regulation was born after the story of 12-year-old Rory Staunton became famous cause.

As his mother Orlaith Staunton had told him, one day, Rory was coming home from school with a fight that he had had in a gym clbad. It did not seem like a big deal, but Rory's health quickly took a turn.

"During the night, I heard him vomit and I went out and he said:" It's my leg, mom, that's my leg. "

His temperature exceeded 103 and he could not keep anything the next day, so she took him to their pediatrician in New York.

The doctor decided that Rory was seized and sent him to the hospital for liquids. Staunton said the emergency room doctors decided that it was just a stomach virus and sent him home. But Rory was getting worse.

"We brought him back to the hospital on Friday night and he pbaded away Sunday night," Staunton said. "He went straight to the intensive care unit when we brought him back in. And it was after his death that we were told that he had died of sepsis."

She says she's never heard of sepsis, even though the disease strikes more than a million Americans a year and kills over 250,000 each year.

Sepsis is an overreaction of the body's immune system to an infection. Fever, chills, breathing difficulties and high heart rate are common symptoms.

If the hospital had correctly diagnosed Rory on his first visit and treated him aggressively, he would probably have lived, Staunton said.

She and her husband, Ciaran, "were angry and wanted to do something that would bring about a change in how sepsis was diagnosed and how people would know what it was," she says.

And as a result of their efforts, the death of Rory in 2012 catalyzed action in the state of New York, which imposed in 2013 the "Rory Regulations", a directive intended for doctors and hospitals on the how to treat sepsis. The key is rapid diagnosis, rapid antibiotic use and careful management of liquids.

Jeremy Kahn, a specialist in intensive care medicine at the University of Pittsburgh, who also studies health policy and management, said doctors like him do not like being directed to how to treat their patients. patients. They prefer to follow the professional guidelines. But as it is amazing that doctors are slow to adopt best practices. And that's true for sepsis.

"The decades of undertreatment of sepsis patients have somewhat weakened our position," said Kahn, "and it's time to be a little more open to accept these regulatory approaches."

But first, Kahn and his colleagues wanted to see if the New York regulations really made a difference. Death rates due to sepsis are declining across the country. The question is therefore whether the New York rules have resulted in a faster improvement compared to other states.

Kahn and colleagues compared the rate of improvement in New York to that of other states and concluded that "these regulations had the effect of reducing mortality," he said. The results were published in JAMA, the journal of the American Medical Association.

One of the reasons some physicians have been reluctant to adopt the regulation is that it expects them to apply a specific set of practices, including a formula that governs the amount of fluid to infuse and the timing of the injection. .

"The clinical community is very concerned that this amount of fluid will harm at least some patients with sepsis," Kahn said. While rules can save lives globally, this can actually be counterproductive. But doctors are not supposed to dismiss it.

It is clearly possible to improve the treatment of sepsis, so the rules need to be flexible enough to incorporate improvements as they appear, he says. "The evidence changes all the time, and when you record [what is currently] "Best practice" in laws or regulations, you become less agile. "

Another question is whether the success of New York would be repeated elsewhere. New York State started much worse than many other states. So it's possible that regulation simply helped the state to get closer to the others, he said.

"It calls into question the kind of impact these regulations will have on other states that could have better sepsis outcomes in the first place," Kahn said.

This is important because a few other states have similar laws or regulations and more than a dozen others are considering them. The Stauntons have created a foundation that is now trying to move this country forward.

Orlaith Staunton says that we just do not want to let the doctor decide.

"It's not enough to say, leave it to me and I'll recognize it when I see it," she said. "Because it's clear that this has not been recognized, I think the good doctors will agree that it's something that needs to be regulated."

She hopes new scientific results will influence some of the doctors and hospitals that resist a government mandate.

It will not happen overnight. Demetrios Kyriacou, an emergency physician at Northwestern University, wrote a precautionary editorial JAMA saying that "major public health interventions can not be based on [Kahn’s] unique observation study. "

"Because the demands placed on nurses and doctors to provide rapid intensive care to patients in critical environments can affect the treatment of patients," he wrote, "any strategy to reduce morbidity and mortality related to sepsis must be based on convincing evidence before being subject to government regulation. "

You can contact NPR Scientific Correspondent Richard Harris at [email protected].

9(MDAzOTg1NjAzMDEyNTIwMDUzMDg0MGQ5NA004))

Source link