[ad_1]

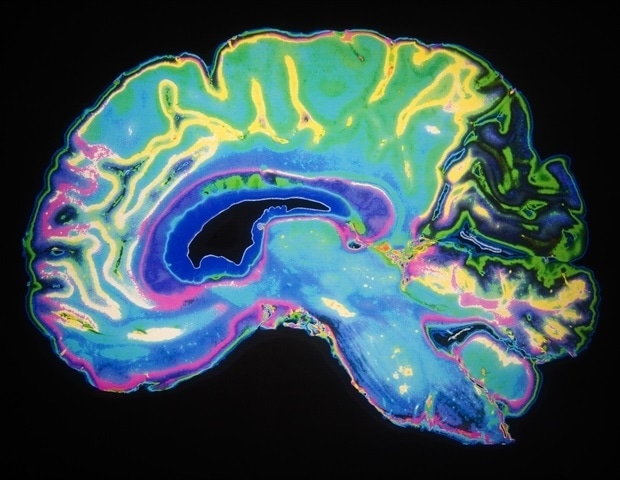

Neuroscientists at the University of Oregon have reported that two areas of the mouse brain badociate representations of what is heard and expected, as well as a behavior that guides the mice toward the best reward .

Researchers know that signals range from ears to brainstem, thalamus and auditory cortex, to the next. What we did not know, is how these sound signals are used by other areas of the brain to make decisions and stimulate behavior.

In a series of studies on mice, researchers at the laboratory of Santiago Jaramillo, professor of biology and member of the Institute of Neuroscience, have identified the posterior tail of the dorsal striatum as a key player. In an article from April 2018 in Nature CommunicationsJaramillo and his colleagues found evidence that neurons in this region provide a stable representation of sounds during auditory tasks.

The follow-up studies published in the Journal of Neuroscience, have sought to better understand what is happening in the auditory sensory system of the mouse brain, Jaramillo said.

In January, his lab reported that the posterior dorsal striatum was receiving signals from two parallel pathways, one from the auditory thalamus and the other from the auditory cortex. The second study, published online on March 5, looked more closely at signal integration.

"The two-way signals tell you very well the frequency of the sounds," Jaramillo said. "That explains why if you close the auditory cortex, you still get the signals you need from the auditory thalamus." In our second study, we studied the integration of sound, action, and reward. We knew that the activity of neurons in these regions of the brain represents sounds, but what about actions and expectations about the reward? "

It turns out that the integration of the response to the reward, or the expectation of a reward learned, is improved in the posterior striatum, researchers discovered using electrophysiological recordings in simple two-choice scenarios.

Initially, 11 adult male mice, representing more than 100 trials, heard brief high and low frequency sound pulses. As a reward, one or two drops of water waited for the mice if they moved to the right or to the left according to the frequency of the sound. At this point, the researchers changed the reward-sound combination to see if the programmed anticipation in the mice could be reprogrammed and influence a directional behavioral change.

Over time, the improved response in the dorsal posterior striatum appeared when mice adapted their movements to seek the greatest reward. The new study suggests that the auditory neurons involved build representations about sounds, actions, and expectations of reward.

"According to the activation of the neurons, the action expected by the mouse will give the best reward," Jaramillo said.

The research in Jaramillo's lab aims to understand how the brain learns to make better decisions. Brain regions and circuits are similar in humans, he noted, but it is unclear whether the sound signals reach the posterior striatum from two lanes.

Dr. Jaramillo said his research could provide clues for therapeutic strategies, including specialized devices to treat human hearing disorders or injuries badociated with stroke or injury.

"What we do in the laboratory is a basic science," he said. "We are trying to understand how a healthy brain works, so future research can use that knowledge to develop better diagnoses and therapies."

[ad_2]

Source link