[ad_1]

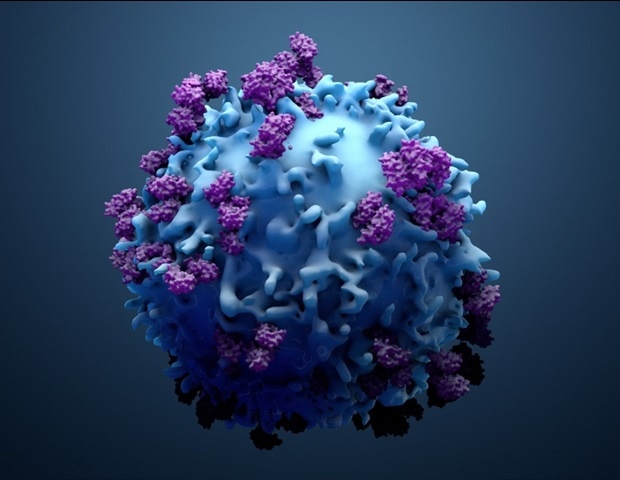

Can T cell tests be used to determine if people have had COVID-19? Scientists from Uppsala University and the Karolinska Institute jointly analyzed this question under the aegis of the COMMUNITY study at Danderyd Hospital. Their study is published in the scientific journal PLOS ONE.

We’ve seen companies sell tests to determine if a person has specific SARS-CoV-2 T cells. It is not that common for T cell tests to be used in clinical diagnostics, so we decided to see if the data from the COMMUNITY study, where we measured antibodies in a large cohort study longitudinally , and also performed T cell studies at a follow-up time, to see if this study could give us any insight into the performance of these tests on an individual level. “

Sara Mangsbo, Immuno-Oncology Researcher, Uppsala University

By analyzing the responses of T cells to different peptide compositions, the researchers found that different pools of peptides produced divergent responses and that there was a risk of false positive responses. In the opinion of scientists, this risk is due to the fact that peptides can give rise to memory T cell responses originating in a way other than an infection with SARS-CoV-2 – from a common cold, for example.

When scientists tried to avoid using peptides that could give rise to these cross-reactions, there was an increase in the specificity of the test – that is, its ability to establish true negative responses – but its sensitivity (ability to detect a true positive response) decreased simultaneously at the time of sampling and analysis, i.e. 4 to 5 months after COVID-19.

“Here, we used the COMMUNITY study, which participants joined at the start of the pandemic, in April and May 2020, allowing us to follow these individuals over time throughout the pandemic. This gives us the ‘assurance that antibodies, which are measured regularly, can give us information as to whether subjects have had COVID-19 or not, “Mangsbo says.

“In the follow-up study, participants with relatively mild initial illness clearly did not always have measurable SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells in their blood. But among those with more severe illness initially , there were more that had measurable SARS-CoV-2 specific T cells in the blood over time. The correlation we found between the severity of the disease and an established and measurable memory response in the blood n It’s not entirely unexpected; but it’s still important to establish, since the use of T-cell testing has been the subject of public debate for many reasons, ”she continues.

“It is also important to say that the blood of subjects does not always contain the memory T cells after the disease is over. Yet the cells in the tissues – which are not measurable by means of a blood test for T cells – may have a role to play in how people get sick from infection, ”adds Thålin, medical specialist and researcher in charge of the COMMUNITY study at Danderyd Hospital and Karolinska Institutet.

“T cell testing will continue to have an important role to play in research and studies, but likely a smaller role in diagnosis and at the individual level for SARS-CoV-2 in particular,” says Charlotte Thålin.

Work to develop a peptide mixture specific to SARS-CoV-2 was carried out in collaboration with Pierre Dönnes and SciCross AB. Peter Nilsson and Sophia Hober from KTH measured the antibodies over time.

The COMMUNITY study

The study is managed and conducted in close collaboration between Danderyd Hospital (the study purchaser), Uppsala University, Karolinska Institutet (KI), KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, SciLifeLab and the Swedish Public Health Agency.

The research group includes Charlotte Thålin, specialist physician and researcher in charge of Danderyd Hospital, as well as two doctoral students: Deputy Senior Consultant Sebastian Havervall and Specialist Physician Ulrika Marking. The other participants were Professors Sophia Hober and Peter Nilsson from KTH; senior lecturer Sara Mangsbo, researcher Mikael Åberg and professor Mia Phillipson at Uppsala University; Jonas Klingström, Associate Professor (Docent) and Kim Blom, PhD, from KI; and the Swedish Public Health Agency.

Source link