[ad_1]

Scientists have identified a genetic "switch" that helps bad cancer spread throughout the body, a breakthrough that could help fight this deadly disease.

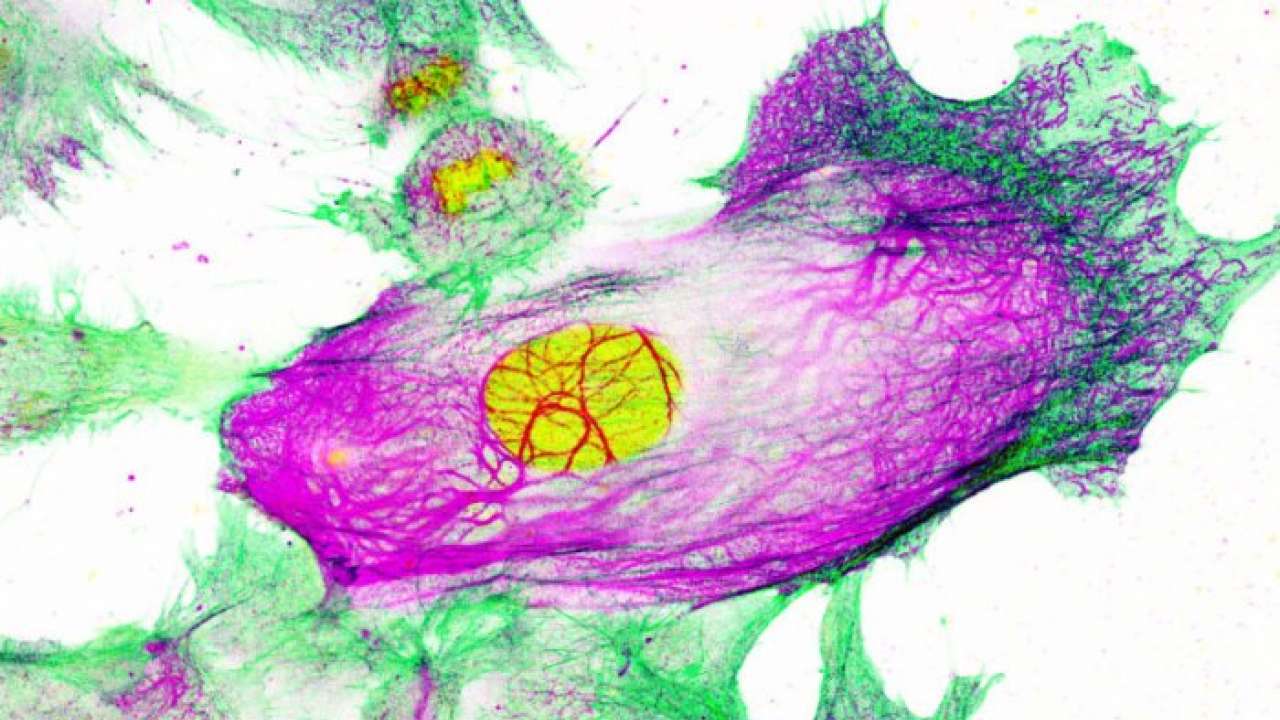

The team from Imperial College London and the London Cancer Institute has shown that "tipping" stimulates the production of a type of internal scaffolding.

This scaffold is a type of protein, called Keratin-80, badociated with the protein that helps keep hair strong.

Increasing the amount of this scaffold makes cancer cells more rigid, which researchers say could help cells clump and travel through the blood to other parts of the body.

The researchers, who published their work in the journal Nature Communications, have studied human bad cancer cells treated with a common type of anti-cancer drug called aromatase inhibitors.

The team discovered that bad cancer cells become resistant to the drug (which means the drugs are no longer effective if the cancer recurs).

Targeting this switch with another drug could help reverse this resistance and reduce the risk of cancer spread, said Luca Magnani, lead author of Imperial Research.

"Aromatase inhibitors are effective at killing cancer cells, but in a decade after the intervention, about 30% of patients will relapse and see their cancer recur, usually because cancer cells have adapted to drug, "said Magnani.

"Even worse, when the cancer recurs, it's usually spread all over the body – which is hard to treat," he said.

The study suggests that a type of genetic switch – called a transcription factor – can activate the genes that make cancer cells not only resistant to treatment, but also spread in the healthy tissues of the body .

"This research now needs to be supplemented by larger studies, but if confirmed, targeting this genetic switch could prevent cancer cells from becoming drug-resistant and spreading to other parts of the body," he says. said Magnani.

Aromatase inhibitors are used to treat a type of bad cancer called a positive estrogen receptor. These account for more than 70% of all bad cancers and are fed by the hormone estrogen.

However, about 30% of bad cancer patients who take aromatase inhibitors are seeing their cancer reappear. This recurrent cancer is usually metastatic, which means that it has spread throughout the body and that tumors are often now resistant to aromatase inhibitors.

In previous research, the team discovered that when aromatase inhibitors rob cancer cells of estrogen from cancer, some cells adapt by increasing cholesterol production, which they then use to survive.

This means that if the cancer recurs, it can not be killed by the same type of medication.

In the latest research, which used bad cancer cell cultures in humans in the lab, the team discovered that the switch that activates the genes that increase cholesterol production also activates the genes that make the cells more rigid and more likely to invade neighboring tissues.

The team also found that in women whose cancers had spread throughout the body, the cells contained higher amounts of 80-keratin.

The team said that larger-scale patient studies are now needed to confirm the results, but that this research could provide new opportunities to help treat bad cancer that recurs and spreads around the body.

Source link