[ad_1]

During a normal delivery, the placenta that supports the development of the fetus during pregnancy is delivered soon after the newborn. But sometimes the placenta becomes so attached to the woman's uterus that it can not be removed without causing mbadive, sometimes fatal bleeding. In many cases, the emergency surgery needed to save the mother's life can prevent her from having other children.

And yet, many people do not know the placenta, although the number of women diagnosed with this virus has quadrupled since the 1980s, rising to one in 272 births. Although this increase is badociated with an increase in the caesarean section rate, the link remains unclear.

"I had never heard the word accreta before it happened to me, and I barely survived," recounts Kristen Terlizziwho founded the CaliforniaAccreta-based national fundamentals in 2017. "A reliable biomarker for detecting this would be incredible, and if there was a way to proactively deal with it, that would be huge."

This distant day may have gone a step further thanks to a discovery made by scientists from Cincinnati Children & # 39; s and the University of Cincinnati.

In a published study August 2, 2019, in Science Immunology, the co-authors describe a surprising link between the risk of accreta and a genetic mutation that prevents the healthy formation of "natural killer" cells, a type of white blood cell that helps the body fight against cancerous tumors and viral infections. Beyond the discovery of the connection, the team then demonstrated in the mouse, accreta could be stopped in its tracks.

"This is a major problem for maternal health," says study co-author Helen Jones, PhD, expert in placental research at Cincinnati Children & # 39; s. "Currently, the only way to diagnose Accreta is to spot it at mid-pregnancy on ultrasound, usually after 18 to 20. Many women never know that they have it before they're in it." arrive at the hospital for labor and delivery. "

If future studies confirm that women with accreta also have NK cell dysfunction, it may be possible to prevent over-attachment and reduce the need for hysterectomies to stop fertility, says Jones.

Accidental discovery connects accreta to defective NK cells

This new discovery dates back to a fundamental science project led by Kasper Hoebe, PhD, a scientist with the division of immunobiology at Cincinnati Children's, who recently left for a new position. His team was looking for gene mutations that could affect NK cells. During this work, Anna Sliz, a graduate student from Hoebe's lab, has encountered a problem.

"In one of our colonies, we observed an abnormally high frequency of reproductive mothers who had unsuccessful pregnancies.When I tried to grow NK cells in these mice, I had a tendency to to have a lower yield than my wild type controls, "says Sliz.

Hoebe and Sliz consulted with Jones, who quickly recognized that the dikes kept placentas conserved with a significant trophoblast invasion, reflecting human accrual – a condition rarely seen in mice. This prompted a new investigation.

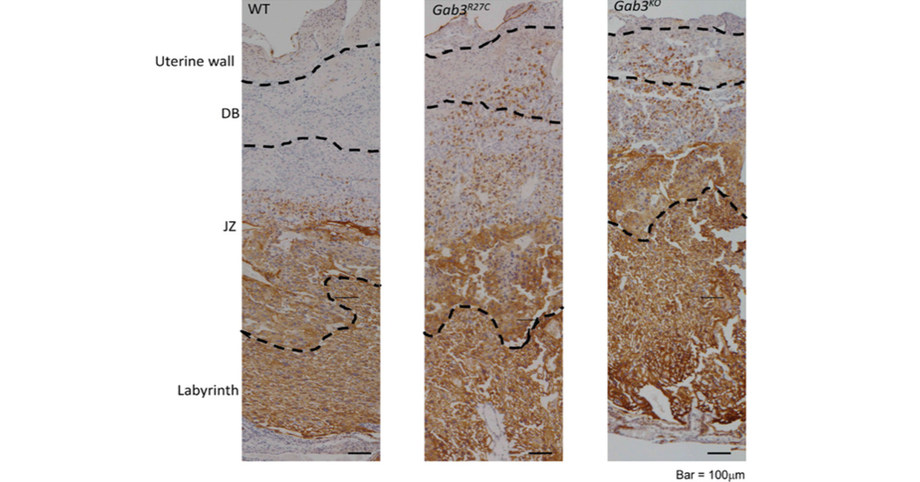

Soon, the collaborators discovered that the mice carried a mutation in a protein called Gab3, which prevented a normal expansion of NK cells in the uterus. The disturbed NK cells then did not do an important job: to disable the process allowing the growing embryo to attach to the tissues of the uterus.

This process, called trophoblast invasion, continues normally until about 20 weeks of pregnancy. But for women with accreta, the process of invasion continues much longer.

"For normal placental development to occur, fetal cell growth must be controlled by NK cells," says Hoebe. "Our studies have shown that in the absence of Gab3, the function of NK cells in the placenta is impaired, resulting in excessive invasion of fetal cells in the uterus."

What does it mean for pregnant women?

Much more research is needed before women can be tested to determine if their NK cells are functioning poorly and whether an NK cell transplant would be safe and effective.

NK cells have been transplanted to treat people with certain forms of cancer, but the potential impacts on pregnancy are not yet known.

"We do not know yet because we still have to study this in humans, and we are working on international collaboration to try to solve this problem," said Jones.

For now, however, the results may remind women to be cautious when they receive caesareans. Previous studies have shown that the risk of growth increases sharply when women have multiple cesareans. Today, these results may help explain why this risk increases, Jones says.

About the study

The research was funded by the NIH grant P30 DK078392 (Center for Integrative Morphology of the Cincinnati Digestive Disease Research Center), the NIH grant R21AI135380 and the Maren Foundation.

Quote: Gab3 is required for the expansion of IL-2- and IL-15-induced NK cells and limits the invasion of trophoblasts during pregnancy. A. Sliz, K.C.S. Locker, K. Lampe, A. Godarova, D. R. Plas, E. Janssen, H. Jones, A. B. Herr, K. Hoebe. DOI 10.1126 / sciimmunol.aav3866.

Learn more about Cincinnati Children's recent research.

SOURCE Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center

Related Links

http://www.cincinnatichildrens.org

Source link