[ad_1]

This is the tweet that let the world know that Michael Rosen is back in shape and on the mend. “My days in a wheelchair are over. Hold on now. Sticky McStick Stick “, he wrote in June of last year, after contracting Covid-19 in March and spending 48 days in intensive care.

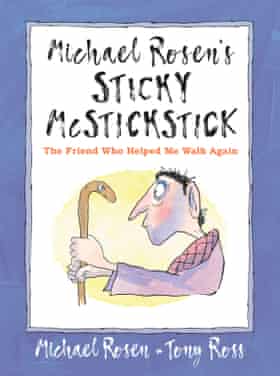

Now the poet and former children’s award winner wrote a touching picture book about Sticky Mcstickstick and his battle with the long Covid in an NHS rehabilitation ward last summer.

Illustrated to great comic effect by Tony Ross, Sticky McStickstick: the friend who helped me walk again details Rosen’s transformation from a man who couldn’t stand on his own to a grandfather who proudly returns home, into the open arms of his beloved family. It is dedicated to his wife and children, as well as to “all the doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and hospital staff who saved my life”.

The 75-year-old author of We go bear hunting, said to Observer: “It’s a way to start a conversation with kids, across generations, about this cycle of disease and trying to recover.”

He hopes the book, which will be released in November, will help children, parents and grandparents struggling with the long Covid and other debilitating illnesses. “One of the things we always say to children is, try harder. We present them great sporting successes – we now watch them all at the Olympics. But I think if I had to list my biggest physical achievements in life, one of them would be learning to walk again last year. This book is a reminder that there are some very, very ordinary things that are amazing as well. “

He found his rehab experience “totally infantilizing” – so it made sense to write a children’s book about it. “Six months earlier, I was teaching narratology at a university. And now here’s someone saying, ‘Michael, throw the ball’ and I say ‘eeurgh’, and the physiotherapist says ‘come on, Michael, you can do it’. “

On another occasion, he was relearning to get up from a bench and was told to put his hands behind him and his nose on his toes. “As a child, for the next few weeks I kept repeating myself: hands behind, nose on toes, hands behind, nose on toes.” He adds, in horror: “I should have put that in the book, right?” Hours later, he emails to say that “nose to toe” was added, at the last minute, to the story: “We kicked it. It’s in! “

As Rosen begins to regain his strength, Ross’s illustrations show him zooming into the hospital in his wheelchair. “I remember a nurse saying, ‘Slow down Michael, slow down,’ he recalls.

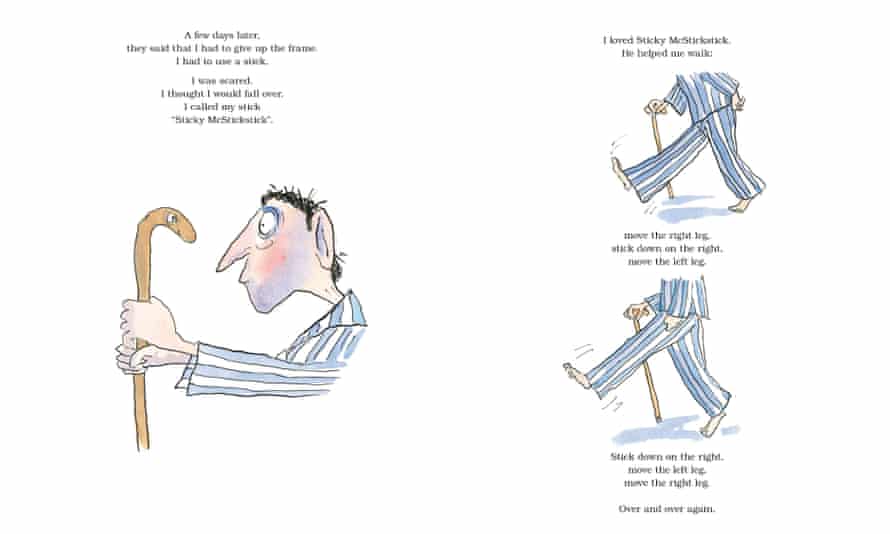

He is then told to start using a cane. “I was scared. I thought I was going to fall,” he writes in the book. But soon he grew to love his Sticky McStickstick. “He helped me walk.

In total, Rosen spent 40 days in a medically induced coma, and when he came out he couldn’t even feed himself. “I sat there waiting for someone to put a spoon in my mouth. I really felt like a one year old.

Writing about his “childhood” experiences in the rehabilitation department helped him cope with the trauma of what happened to him, he says. He has lost most of the sight in his left eye and most of the hearing in his left ear, and still has bouts of dizziness. “You realize that you have changed so much, fundamentally, physically and so on. And that life has changed, for all of us. It seems to take a lot of work. You have to do a lot of mental work, thinking about your frailty and how fragile you are. “

He found he could sit in a room and linger over it. “I have to make an effort not to get carried away or prevent myself from doing things.” He fears that many others are in the same situation. “Sometimes you have the impression that the country has experienced some kind of war. There were no guns, bullets or bombs, but the pandemic has had a huge and profound effect on hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people. It is not a war, but it is a trauma – personal, for many people, but also societal.

Although he no longer needs her support, Rosen keeps Sticky McStickstick. When he sees his old friend staring at him as he walks out the door, it is a poignant reminder of his difficult journey, “the wonderful people” who took care of him and all he accomplished. “He’s my reward.

[ad_2]

Source link