[ad_1]

Research and discoveries must be shared. And when these discoveries are publicly funded, they should be freely available. Academic journals are the main forum used by researchers to share new discoveries with other researchers, especially in the field of science. For most academic journals, university libraries pay subscription fees on behalf of students and researchers.

However, over the last 20 years, there has been pressure to make newspapers freely accessible to anyone with an Internet connection. In response, research funders have announced open access policies in the United States, Canada, Australia, South America and Europe.

Open profits

Commercial academic publishing has been extremely profitable for a long time. Researchers generally access journals in their field using subscriptions from their university library. Because these journals are essential to the work of researchers, publishers have spent the last 30 years increasing their prices faster than inflation.

The importance of journal subscriptions for researchers has helped publishers like Elsevier make huge profits. Elsevier earns so much money that their president tries to publicly downstimate their profitability.

But open access – which allows anyone to read the articles – was supposed to change all that. Many advocates of open access argued that open access would save libraries money. Open access journals do not charge subscription fees, but many of them charge researchers a fee to publish them. However, authors can publish for free in most open access journals.

Like many researchers, I am dissatisfied with the current publishing system and have applied my research skills to study aspects of open access and its impact on researcher publication habits.

In theory, competition between publishers should limit the price of open access. For example, Jeff MacKie-Mason, economist and librarian at the University of California, argued that free paid access to publish would reduce the market power of publishers. If academics use research funds to publish, they will be encouraged to consider the cost of publishing with a given journal. This may seem logical, but it remains to be seen if this really happens. In my recent article, I tried to answer this question.

Read more:

Vanity and predatory academic publishers corrupt the quest for knowledge

If the higher fees result in fewer academics wishing to publish with a journal, then when a journal introduces or raises its fees, it should see a reduction in the number of published articles. Unfortunately, I have not found any evidence that this is the case.

In order to examine whether academics are price-sensitive, I've looked at two main scenarios in which one might expect a newspaper to lose value as it becomes more and more expensive: when a newspaper introduces fees and that newspapers increase their prices.

Communication costs

Publish for free is good, but when newspapers start charging fees to researchers, they do not lose customers. A new journal may introduce fees after a free introductory period. For example, when eLife a publication fee of USD 2,500 in 2017, the number of articles published in 2017 and 2018 was not lower than in 2016. Similarly, Royal Society Open Science introduced fees of $ 1,260 in 2018 and continued to grow.

Shaun Khoo

Journals sometimes also become open access. They may believe in the ideal of free access or want to pick up speed the slowly pushed changes by donors and universities.

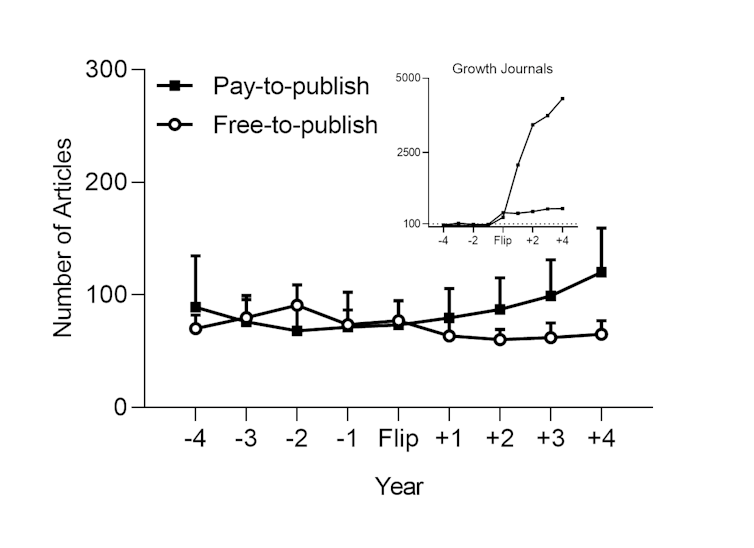

For an established review that becomes open access, charging fees may be badociated with journal growth. I reviewed 19 open access journals between 2006 and 2014, of which 11 started charging fees and 8 became free to publish and read. Reviews of the introduction of fees do not suffer any reduction of articles. In fact, two journals began publishing hundreds of more paid articles than subscription-based, perhaps because of the lack of space in the online publication or the fact that they now had a commercial interest in publishing more newspapers. .

Increase fees, increase revenue

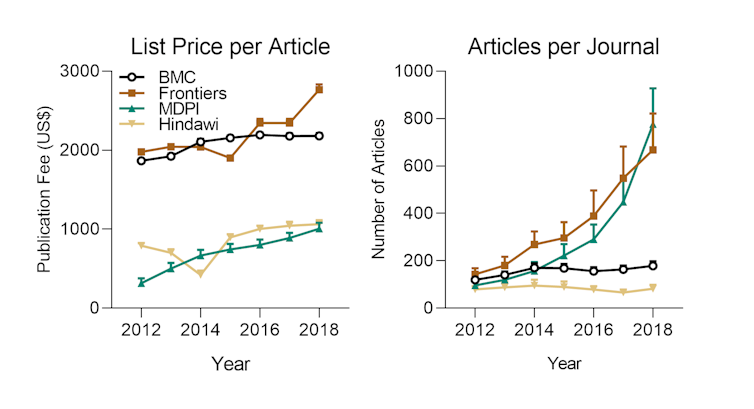

I then examined the four largest open access commercial publishers that used publication fees: BMC, Frontiers, MDPI and Hindawi. I have followed 319 of their journals, their quoted prices and the number of research papers that they have published between 2012 and 2018. I have introduced these data in a statistical model and this showed that academics preferred to publish in more expensive journals.

The two publishers who increased their prices the most, Frontiers and MDPI, also posted the highest growth in the average number of articles in each review.

Shaun Khoo

Pay to publish or perish

Academic journals are not just communication tools, they are also a mechanism for evaluating performance. How many articles and where they are published is supposed to demonstrate the quality of the work of an academic (even if it is not the case). Publishers know this and are happy to admit that their journals are priced according to the payment capacity of this domain and the reputation of their journals. So it's not surprising that open access publishers can make profits up to 50%.

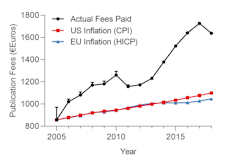

Shaun Khoo, using data from OpenAPC

Even with less than 20% of the market, open access publishers were able to increase their prices much faster than inflation. Mandating the increased demand for open access publishing through donor policies, such as Plan S, will likely cause researchers to spend more on publication and less on research.

In other words, a completely open world of access with our current publishing ecosystem would give academics the choice of paying more to publish in higher-priced, higher-priced journals, or risking their careers, hoping that institutions and donors will be satisfied. valuable newspapers. It's an easy choice when you're under contract or short-term, even if the research and the taxpayers who fund us are the losers in the long run.

The problem of rising publication costs and the insensitivity of university awards is just one of the many perverse stimuli badociated with fee-for-exchange exchanges that feed predatory publishers and deprive academics of their rights.

Read more:

How the Open Access Model Harms Academics in the Poorest Countries

Rather than creating an academic academic press and claiming that the laws of the marketplace will make things work, we should create a public infrastructure to share search results such as pre-print servers, institutional repositories or free open source publishing. These resources allow academics to share free versions of their articles or take ownership of the publishing process, so that new knowledge benefits everyone, not just publishers.

Source link