[ad_1]

REINCARNATION IS ONE religious principle in India. He has also traditionally guided the lives of businesses. Among the most powerful companies in the country, many companies have appeared dead and buried under a mountain of debt, but state-controlled banks, eager to do so, are ready to "extend the deadlines and pretend that debtors politically connected will pay. In the 1990s, after India liberalized its economy, a government report warned that it was "impossible to liquidate and liquidate an unsustainable enterprise." Another in 2001 described the agency handling such actions as "notoriously dilatory". As a third concluded in 2015, in the absence of "looming liquidation threat", debtors did not feel compelled to "resolve their financial difficulties".

All this was supposed to change in May 2016, when Parliament adopted a modern regime of insolvency. Even a small missed debt payment would push a company into bankruptcy proceedings. These could not exceed 270 days. The owners and managers of an insolvent company would lose control of a creditor committee. The Governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBIAt the time, Raghuram Rajan saw the law as a way to eliminate the irreducible impbades of the financial system. Narendra Modi, the pro-business prime minister, hoped this would take India out of the basement of the World Bank's "ease of doing business" ranking. Lawyers saw it as the most important reform since the end of the Raj License in 1991, perhaps since independence in 1947.

Upgrade your inbox and receive our Daily Dispatch and Editor selections.

This month, the bad shots have found a life force. First, a decision of the Supreme Court in early April annulled a RBI Ordinance that ordered banks to automatically return large companies in arrears to the insolvency regime. Lenders, including those owned by the state, actually regained the discretion to extend and pretend what the law was supposed to remove. Then, on April 12, the court virtually suspended the bankruptcy proceedings of Essar Steel, a company with a financial debt of 494 billion rupees ($ 7 billion).

The Essar decision is the heaviest breach ever made to the nascent insolvency regime. The company has been stiffening its creditors since 1999 and is listed on the RBIThe list of "dozens" of companies, which accounted for a quarter of the non-performing debt of the banking system, was at the forefront of restructuring. The family of the founders of Essar, Shashi and Ravi Ruia, which holds a majority stake, was specifically excluded from the auction of the bankruptcy last October. The winning bid of 420 billion rupees to be paid to creditors and an additional 80 billion rupees to boost operations came from ArcelorMittal, a rival steelmaker based in Luxembourg and controlled by Lakshmi Mittal, a billionaire billionaire. Indian origin.

The latest decision makes ArcelorMittal, which would have opened an office in Mumbai to manage the takeover, in limbo. The court ruled that the dispute over the creditors to be paid should be resolved before he took control. We guess how long it will take. At the same time, the Ruias tried to circumvent their exclusion by proposing an offer on Essar, with Russian money, which would cover the 544 billion rupees of debts, including financial debts.

The Essar case puts an end to a series of victories for reformers in bankruptcy. In May 2018, Tata Steel, a major steel producer, acquired Bhushan Steel, another "dirty dozen" company. Creditors recovered 76% of their claims. Five other companies on the RBIWere bought and two others liquidated. The law also reportedly forced Naresh Goyal, another tycoon, to resign as president of Jet Airways and hand over control of his troubled carrier to lenders in March. It was a rare case of a large Indian company snatched from a founding shareholder. These "promoters" were considered irremovable.

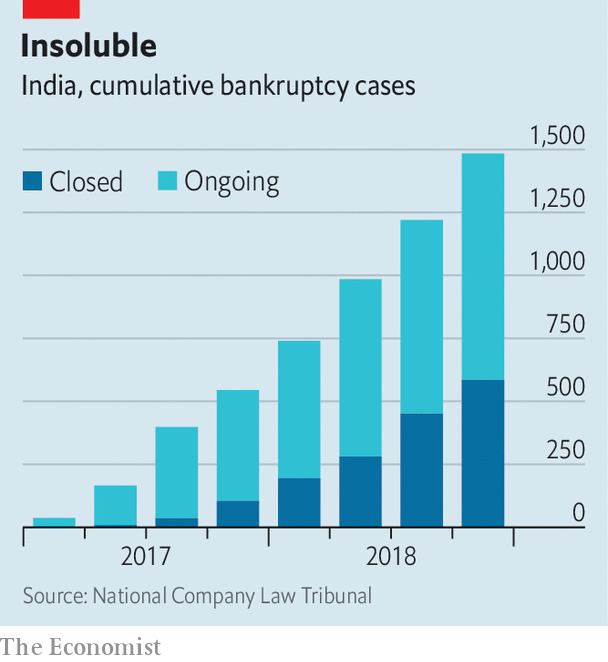

In total, 1,484 companies entered the insolvency system in the last two years. Although no comparable statistics exist for the previous period, it is certainly a huge leap. Thirty-two of them were liquidated and 79 restructured, which involves the repayment of more than a fifth of debts and often an acquisition. Since March 2018, the level of NPLs on the balance sheet of Indian banks has begun to decline.

However, it may be inevitable that the law comes up against bureaucratic inertia and politics. The 270-day delay is more of an aspiration than reality; two-thirds of the cases have exceeded it. In the bustling courtyard of Mumbai, established on the sixth floor of a ruined court building, the three courtrooms are so full that it's hard to see the chairs. The badurances that more space and judges will come are treated with skepticism. The backlog of files is increasing (see graph). The same goes for court challenges.

Reorganizing a large part of the bureaucracy in a country with a heavy bureaucracy will never be easy. In addition, the timeless but well-connected tycoons behind some of the mighty Indian conglomerates were no less powerful. Cautious optimists, like Debanshu Mukherjee of the Delhi-based Vidhi Center for Legal Policy, talk about youth issues. For those who consider Essar as a test for the new diet, it sounds more like a kick in the teeth.

Source link