[ad_1]

Photographer: Graeme Sloan / Bloomberg

Photographer: Graeme Sloan / Bloomberg

They are still in the minority, but investors and economists who think America is in a period of inflation – perhaps severe – are starting the year with new weapons for their arguments.

Vaccines offer the prospect of ending pandemic restrictions that could bring consumers back. That’s what economists call pent-up demand – a label that literally applies right now. The new Biden administration is likely to support household spending with more financial aid, after this month’s Senate elections gave Democrats a majority. And in the background, the dollar is weakening and commodity prices have been rising steadily for months.

All of this has pushed up the bond market’s measures of expected inflation. The said break even 10-year Treasury bill rate climbed above 2% last week to its highest level in more than two years.

Yet the prevailing view among economists – including, most importantly, the Federal Reserve – is that it will be years before the United States has to worry about inflation.

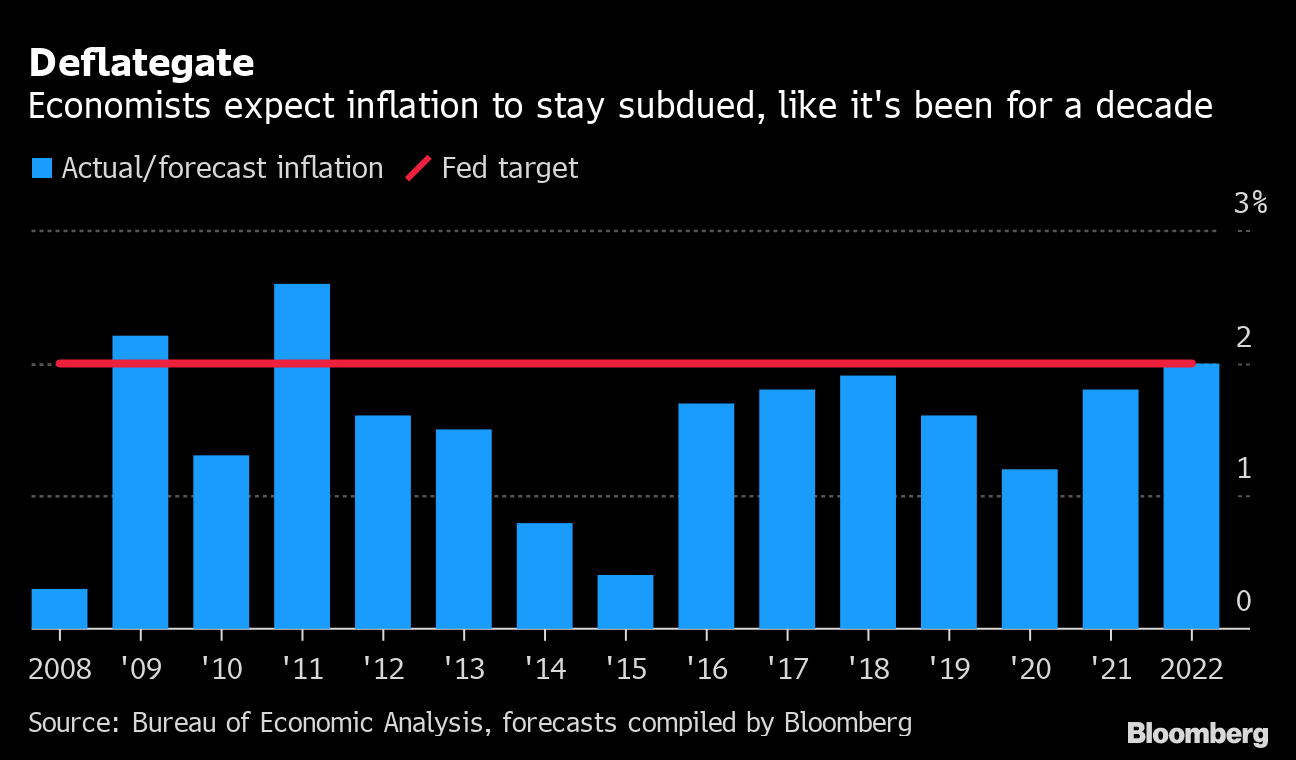

Deflategate

Economists expect inflation to remain subdued, as it has for a decade

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, forecast by Bloomberg

Data due Wednesday is expected to show that consumer prices rose 1.3% in 2020. With rising costs to producers, almost everyone is predicting a higher rate this year. But even by the end of 2022, the Fed’s preferred measure will not exceed its 2% target, according to economist polls. And Fed officials say they want to see inflation stay above that level for a while before raising interest rates.

Inflation skeptics point out that labor markets are still depressed by the virus, deeper demographic and tech trends that are keeping prices down, and the risk that politicians will interrupt support for the economy too early – as they did in the recent past.

So is inflation on its way back? Here are some of the main arguments from each side.

Yes, because: the pumps are primed …

The policy settings just got changed even more towards the “run-it-hot” end of the dial. Budget spending has been the engine of the recovery from the coronavirus crisis, and President-elect Joe Biden – who promises to do more – has a clearer path to pushing his plans through Congress after Democrats won the two Senate seats in January. 5 vote in the second round in Georgia.

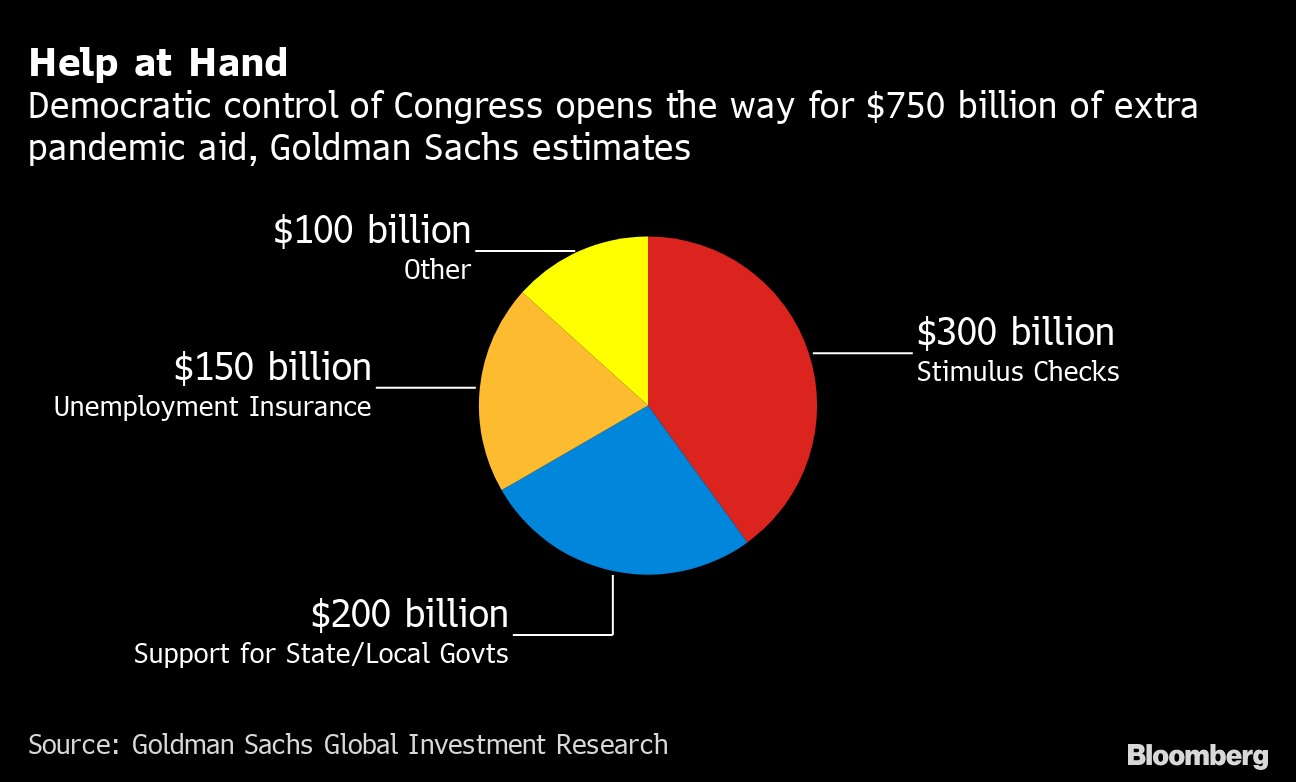

Help at hand

Democratic oversight of Congress paves way for $ 750 billion in additional pandemic aid, says Goldman Sachs

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

“Biden’s agenda is on the line again, which means even more fiscal expansion in the near term,” says Aneta Markowska, chief economist at Jefferies. She expects 10-year Treasury yields, which topped 1% last week for the first time since the pandemic hit in mid-March, to reach 2% by the end of the year. ‘year.

Meanwhile, the Fed, which can’t do much to speed up the economy right now, remains in charge of the brakes – and promises not to hit them anytime soon. After consistently falling short of its target, the Fed’s new policy is to let inflation exceed and stay there – so on average 2% over time – before raising borrowing costs to calm things down. .

… V is for vaccines…

United States. The economy has moved closer to a V-shaped recovery than it seemed likely earlier in the crisis, and vaccines could complement the job.

Americans are already spending more on goods than before the virus. If that’s not yet the case with the services, it’s only because lockdowns have taken away options from consumers – which is expected to change as more people are vaccinated.

Morgan Stanley economists expect “a strong rebound in demand, especially in Covid-sensitive sectors such as travel and tourism”, as vaccines will be more widely deployed in the spring. They predict that core inflation, which excludes the prices of commodities like food or gasoline because they are more volatile, will hit the 2% threshold this year and exceed it in 2022.

… And households are flush with

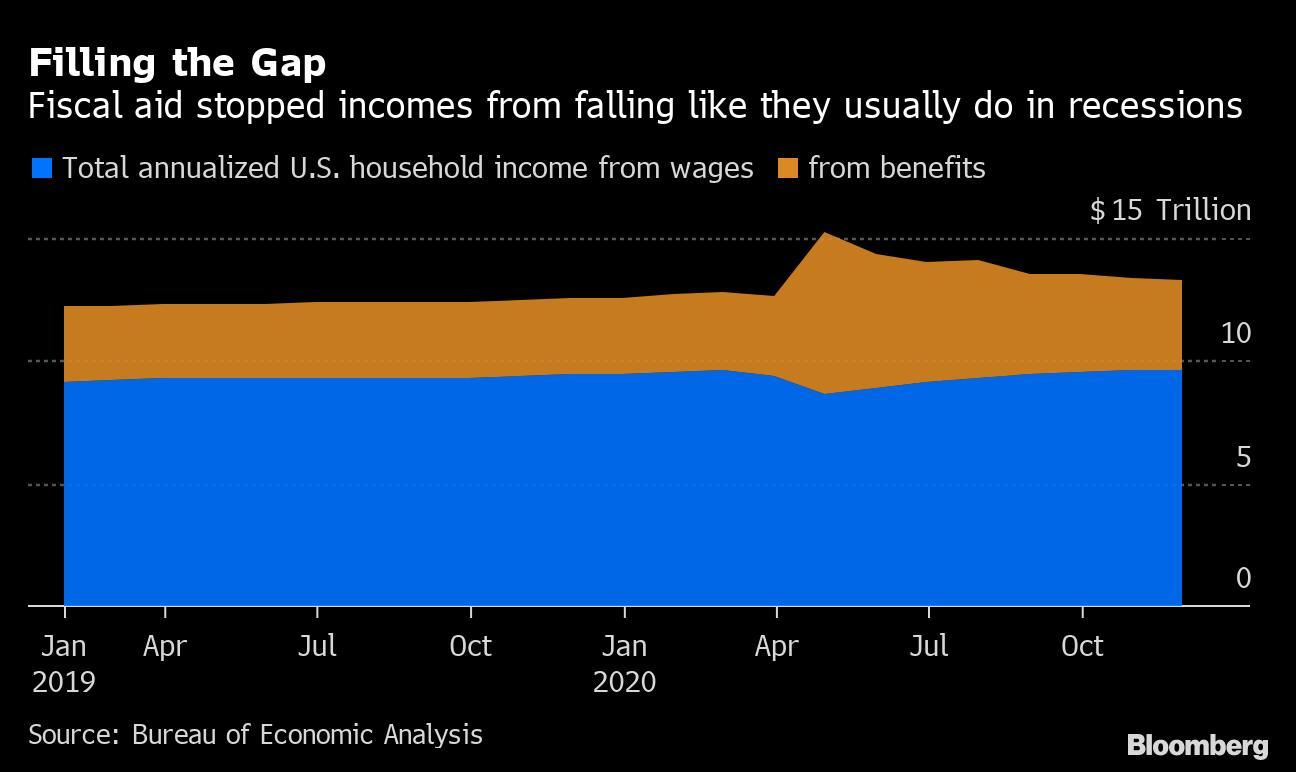

Stimulus checks and higher unemployment benefits have pushed up household incomes overall even as economic output fell – a rare combination. And rising stock and real estate markets helped add more than $ 5 trillion to U.S. household net worth in 2020.

Fill the void

Tax assistance has kept incomes from falling as they usually do during a recession

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

High-income people and the elderly, more likely to self-quarantine, have accumulated savings while waiting for the pandemic, says Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics. They’ve missed out on things like trips to the hairdresser, vacations, and out-of-town meals – and they’re “in an uniquely good financial position to increase spending on these services once they get there. feel sure.”

No, because: this time it’s no different …

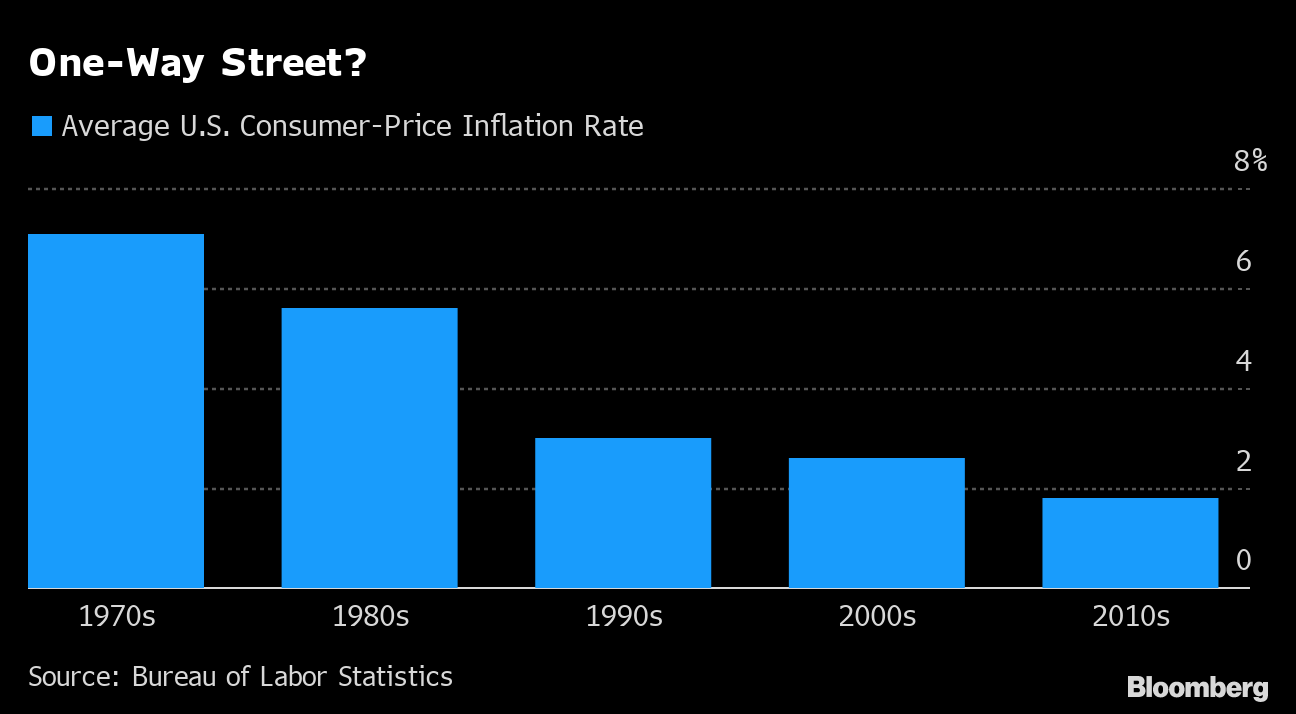

The gradual disappearance of inflation is one of the most entrenched trends in the economy. And the political response of all hands at the pump to the pandemic is not entirely unprecedented. After 2008, the government and the Fed also pumped money into the economy, causing many to predict inflation that never happened. Budget spending has been bigger this time around, as has the hole in the economy it needed to fill, so the result won’t necessarily be overheating.

One-way street?

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

This decade so far looks a lot like the last, says Ben May of Oxford Economics. “Insufficient demand has been countered by looser monetary and fiscal policy. This boosted asset prices, but core consumer price inflation remained low. “

Another lesson from the financial crisis is that American politicians are not always the popular caricature spenders. They may in fact suffer from the opposite bias – toward tighter fiscal policy than the economy needs. This is what happened after the 2008 crash, slowing the recovery, economists concluded. And while a more tolerant view of deficits has set in since then, Biden’s Democratic Party still contains its share of budget hawks.

… There is still some slack …

Even optimistic forecasters say it will be years before the United States employs as many people as it did in 2019, when the unemployment rate was the lowest in half a century.

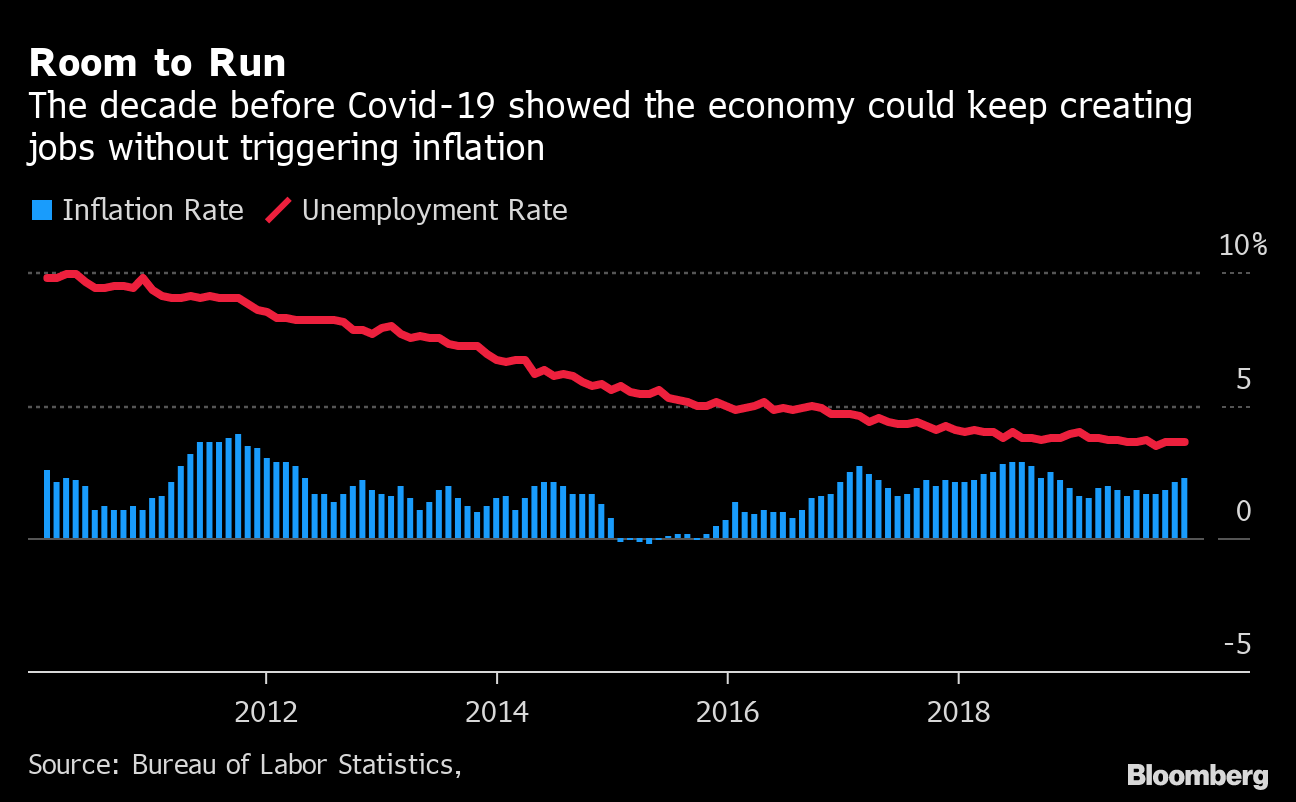

An economy that does not use all of its available resources, such as labor, usually has room for growth without triggering inflation. And a key lesson from the long expansion of the 2010s was that these resources were more important than previously thought.

Space to run

The decade before Covid-19 showed that the economy could continue to create jobs without triggering inflation

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics,

This may also be true for the post-pandemic economy. Goldman Sachs, for example, raised its growth forecast after the Georgia election and now sees the economy grow 6.4% this year – recouping all Covid losses and more. But he still does not expect core inflation to exceed 2% – which will cause interest rates to rise – until 2024.

What Bloomberg Economics Says

The weak dollar, rising energy prices and an oddity in calculating hourly earnings “create an illusion of increasing inflationary pressures.” However, these transitional developments will ultimately be overcome by a significant economic downturn. Without a collapse in work participation linked to the pandemic, the unemployment rate would be closer to 9.5% rather than the 6.7% last reported. If unemployment were north of 9%, and not south of 7%, the rhetoric of inflationists would be considerably more muffled.

– Carl Riccadonna, Chief American Economist

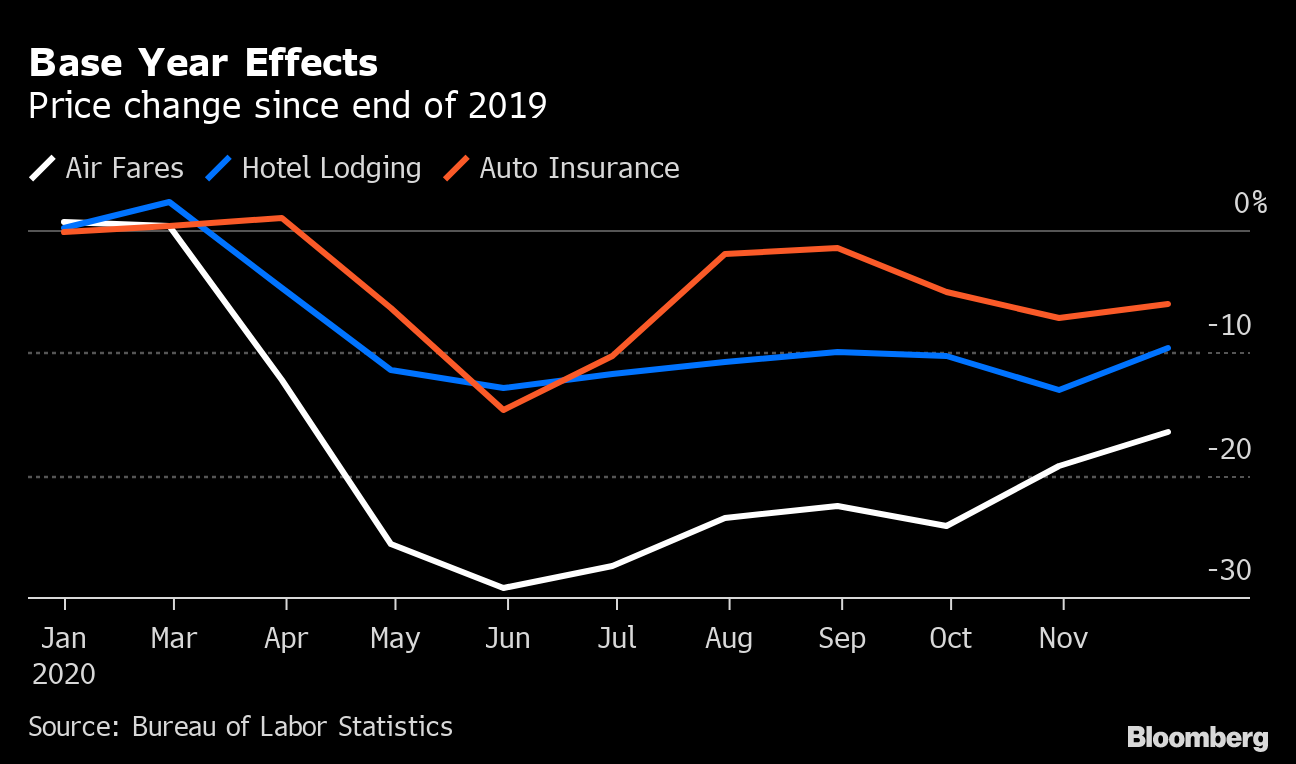

… And unique pieces don’t count

The sudden drop in prices for some services in the spring of 2020 will disappear from the annual calculations in the months to come – pushing inflation up even if these prices do not return to normal.

Base year effects

Price change since the end of 2019

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

But for monetary economists, higher prices only really count as inflationary when they fuel expectations of even higher prices in the future, generating snowball-like momentum that could become difficult to control. That was America’s experience in the 1970s, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell told reporters last month – but not more recently, and likely not at the end of the pandemic.

Asked about the risks of pent-up demand, Powell said the Fed would be predisposed to view any resulting spikes in prices – airline tickets, for example – as “a one-time price hike, rather than a rise in core inflation.” This is not something that would get the Fed to act.

– With the help of Benjamin Purvis

Source link