[ad_1]

The debate on describing low-risk lesions in a way that avoids the word "cancer" has been going on for some time since the National Cancer Institute proposed the idea in 2013.

A study now suggests that the name given to these low-risk lesions has a substantial impact on how patients view their clinical situation, and the authors claim that the use of the word "cancer" causes excessive treatment.

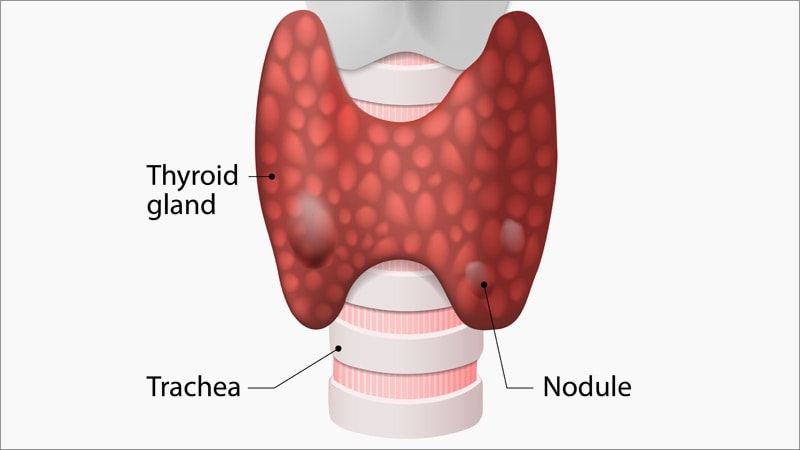

The study was based on a survey of 1,000 healthy people surveyed about their reactions to the hypothetical discovery of a low-risk lesion in the thyroid gland.

As for the low-risk lesions found, for example, in the prostate, these may never become invasive cancer and can be treated with active surveillance instead of radical treatment at first.

The results of this survey show that participants were almost three times more likely to choose an invasive treatment that worsened their prognosis if the lesion was described as cancer rather than if it was called a nodule or tumor.

The study was published online on March 21 in JAMA Oncology.

"The cancer label profoundly influences the choices made by patients with low-risk malignant neoplasms," write the authors, led by David R. Urbach, MD, Department of Surgery and Institute of Health Policy, University of Toronto. Toronto, Women's College Hospital, Canada.

"It can lead to paradoxical decision-making leading to excessive treatment," they warn.

However, in a related editorial, Elise C. Kohn, MD, and Shakun Malik, MD, Cancer Treatment Evaluation Program, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland, raise some questions about the study and the idea not to use the word "cancer."

"What's in a name?" they ask, adding: "Are all the small lesions containing abnormal cells the same?

"This brings us to the following question: Is it ethical to generalize the argument that any small malignant lesion that can be cured more than 95% of the time can be minimized as non-cancer?"

Kohn and Malik argue that "the application of a benign descriptor can create or propagate a treatment bias just as much as the use of a more correct and disturbing term, such as cancer" .

They also suggest that the responses of generally young and healthy individuals who participated in this study may not match the responses of "older patients who may have nodules in the lungs, bad, pancreas or other organ".

Calling for a "careful design of the experiments", Kohn and Malik believe that one must pay attention "to the magnitude and depth of the conclusions and attributions".

It is not always an easy task for busy clinicians to communicate risks and recommendations and to enable informed decision-making when explaining the diagnosis of low-risk lesions to patients, recognize editorialists. But they stress that "patient care is a shared decision-making exercise that requires clear communication."

Details of the study

In their article, the researchers point out thyroid cancer as an excellent example in which an unfounded fear can drive patient choices.

They note that, although the incidence of the disease has increased in the United States faster than that of any other malignant tumor, this increase is almost entirely due to low-risk lesions.

Their study aimed to determine whether the label given to a thyroid neoplasm would affect the patient's decision-making. They interviewed a sample of US residents aged 18 to 78 years.

Participants were presented with hypothetical vignettes involving low-risk thyroid neoplasms with three attributes:

-

Disease label: cancer, tumor, nodule

-

Treatment offered: active surveillance, surgery

-

Risk of progression or recidivism: 0%, 1%, 2%, 5%

In all vignettes, individuals were informed that their probability of survival was greater than 99%.

For the test, participants were presented with pairs of vignettes and were asked which they preferred. The process was repeated for eight rounds. At each turn, the thumbnails varied according to their attributes and levels.

Researchers excluded those who did not respond to the survey or who took more than 2 minutes, leaving 1086 people responding to 8544 choices.

The median age of participants was 35 years and 56.7% were women. The majority (67.5%) reported good or very good overall health and most (70.9%) had at least a post-secondary degree.

Only 7.3% of people had a history of cancer or thyroid surgery.

The researchers found, unsurprisingly, that most individuals preferred a progression or recurrence risk of 0%. The most-avoided attribute was a 5% progression or recurrence risk.

Active monitoring was preferred over surgery, and the "nodule" and "tumor" labels were preferred to "cancer".

Participants aged 50 and older were more likely to prefer "nodule" and avoid the word "cancer" than those aged 18 to 30, and they were more likely to avoid surgery.

Older, healthy participants also showed a greater preference for active surveillance.

The team showed that the preference for "nodule" over "cancer" was comparable to the 1% risk of progression or recurrence over a 5% risk.

Participants' preference for "tumor" rather than "cancer" was less strong; he compared the preference for a risk of progression or recurrence of 2% compared to a risk of 5%.

Surgery became more acceptable if the disease was labeled "nodule" rather than "cancer"; the preference for active surveillance was higher than that for "tumor" versus "cancer".

The researchers examined in a subset of 516 participants the likelihood that they would choose a radical and invasive treatment that would lead to a darker prognosis.

This so-called paradoxical choice was made by 27.3% of individuals when the disease was described as "cancer", but it was chosen only by 9.4% if the label was "nodule" or "tumor" "(risk ratio of 2.9).

"This paradoxical decision-making suggests that withdrawal from the disease, even at the expense of prognosis, is a strong instinct when we label the disease as a cancer," writes the team.

The research was funded by the Toronto General Research Institute with funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The authors did not reveal any relevant financial relationship.

JAMA Oncol. Posted online 21 March 2019. Abstract, Editorial

To learn more about Medscape Oncology, follow us on Twitter: @ MedscapeOnc

[ad_2]

Source link