[ad_1]

People in religious congregations tend to be happier and more civically engaged than non-religious adults or inactive members of religious groups, according to a new Pew Research Center badysis based on data from Surveys from the United States and from more than two dozen other countries.

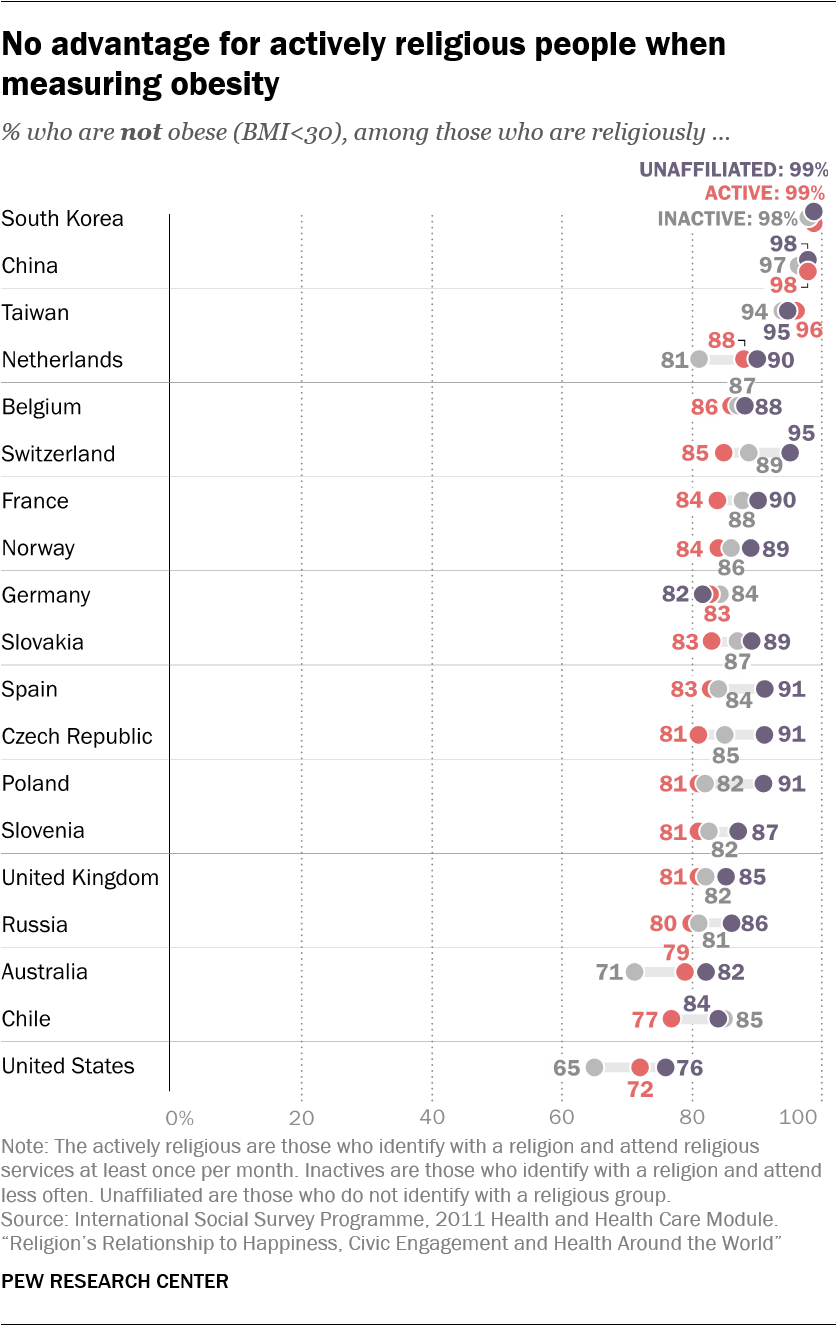

Religious activists also tend to smoke and drink less, but they do nothealthier in terms of frequency of exercise and obesity rates. Moreover, in most countries, people who are very religious are not more likely to consider themselves to be in very good health, although the United States is one of the possible exceptions.

Many previous studies have found positive badociations between religion and health in the United States. Researchers have shown, for example, that Americans who regularly attend religious services tend to live longer.1 Other studies have focused on more limited health benefits, including how religion can help bad cancer patients cope with stress. On the other hand, there are also studies that have not established a strong connection between religion and better health in the United States, and even some studies that have shown that negative relationships, such as higher rates of obesity among very religious Americans. (For more information on previous studies on religion and health, see this sidebar.)

Researchers at the Pew Research Center have taken a global and international approach to this complex topic to determine whether religion has clearly positive, negative, or mixed badociations with religion. eight different indicators individual and societal wellbeing available from international surveys conducted over the last decade. This report examines in particular the self-rated happiness levels of the respondents to the survey, as well as five measures of individual health and two measures of civic participation.2

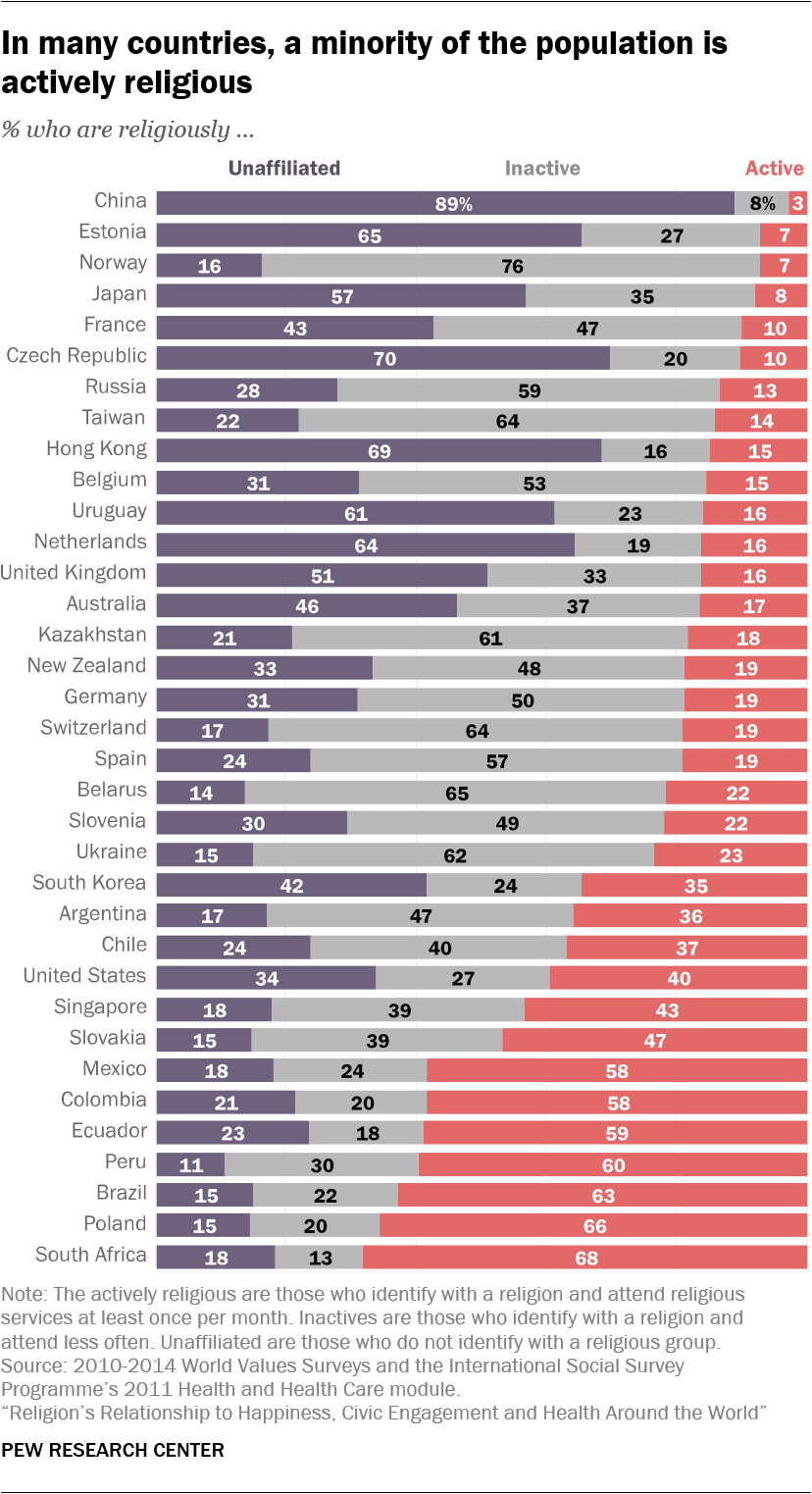

By dividing people into three categories, the study also seeks to isolate the religious character Affiliate or religious participation – or both, or neither – is badociated with happiness, health, and civic engagement. The three categories are: "Actively religious", consisting of people who identify with a religious group and say they attend offices at least once a month (sometimes called "badets"); "Inactive religious", defined as those who claim a religious identity but attend services less often (also called "inactive"); and "without religious affiliation", people who do not identify with any organized religion (sometimes called "no").3

This badysis shows that in the United States and in many other countries of the world, regular participation in a religious community is clearly linked to higher levels of happiness and civic engagement (in particular, voting in elections and joining community groups or other voluntary organizations). This may suggest that societies with declining levels of religious commitment, such as the United States, may experience a decline in personal and societal well-being. But the badysis reveals relatively little evidence that religious affiliation, in itself, is badociated with a greater likelihood of personal happiness or civic involvement.

In addition, the five health measures present a mixed picture. In the United States and elsewhere, religious people are less likely than others to adopt certain behaviors that are sometimes considered sins, such as smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol. But religious activity does not have a clear connection to the frequency with which people exercise or if they are obese. And, after adjusting for differences in age, education, income and other factors, there is no statistical link between active religion and better health reported in one of the 26 countries and territories surveyed with the exception of Taiwan, Mexico and the United States. States.4

Even in the United States, the strength of the link between religion and health varies with the measures and data sets used. For example, in some years, the General Social Survey has shown that people affiliated with a religion who go to church or other religious services at least once a month are particularly likely to to say oneself in excellent health, whereas in recent years not been the case. (See the box on the United States).

The exact nature of the links between religious participation, happiness, civic engagement and health remains unclear and needs to be deepened. Although the data presented in this report indicate that there are links between religious activity and some measures of well-being in many countries, the numbers do not match. prove going to religious services is directly responsible for improving people's lives. It may be that some types of people tend to be active in many types of activities (secular and religious), many of which may offer physical or psychological benefits.5 In addition, these people may be more active in part because they are happier and healthier rather than the opposite. (For more information on the possible causes of these links, see this sidebar.)

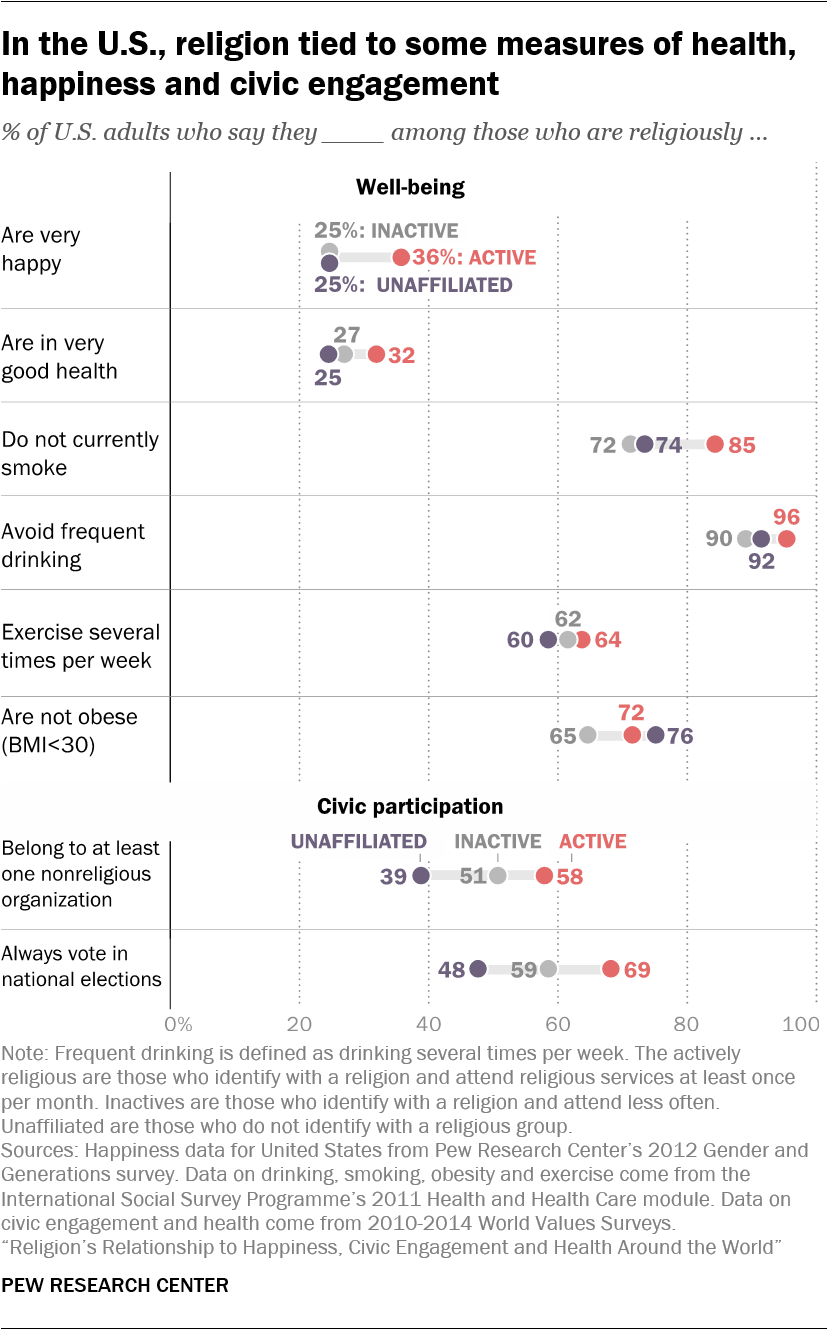

Whatever the explanation, more than a third of American adults (37%) who say they are religious and very religious say they are very happy, against only a quarter of Americans inactive and unaffiliated. Among the 25 other countries for which data are available, the badets report being happier than non-affiliates, with a statistically significant margin in almost half (12 countries) and happier than unintentionally religious adults in about one-third ( nine) countries.

The gaps are often striking: in Australia, for example, 45% of actively religious adults say they are very happy, compared to 32% of inactive people and 33% of non-members. And there is no country in which data show that badets are significantly less happy than others (although in many countries there is not much difference between badets and all others).

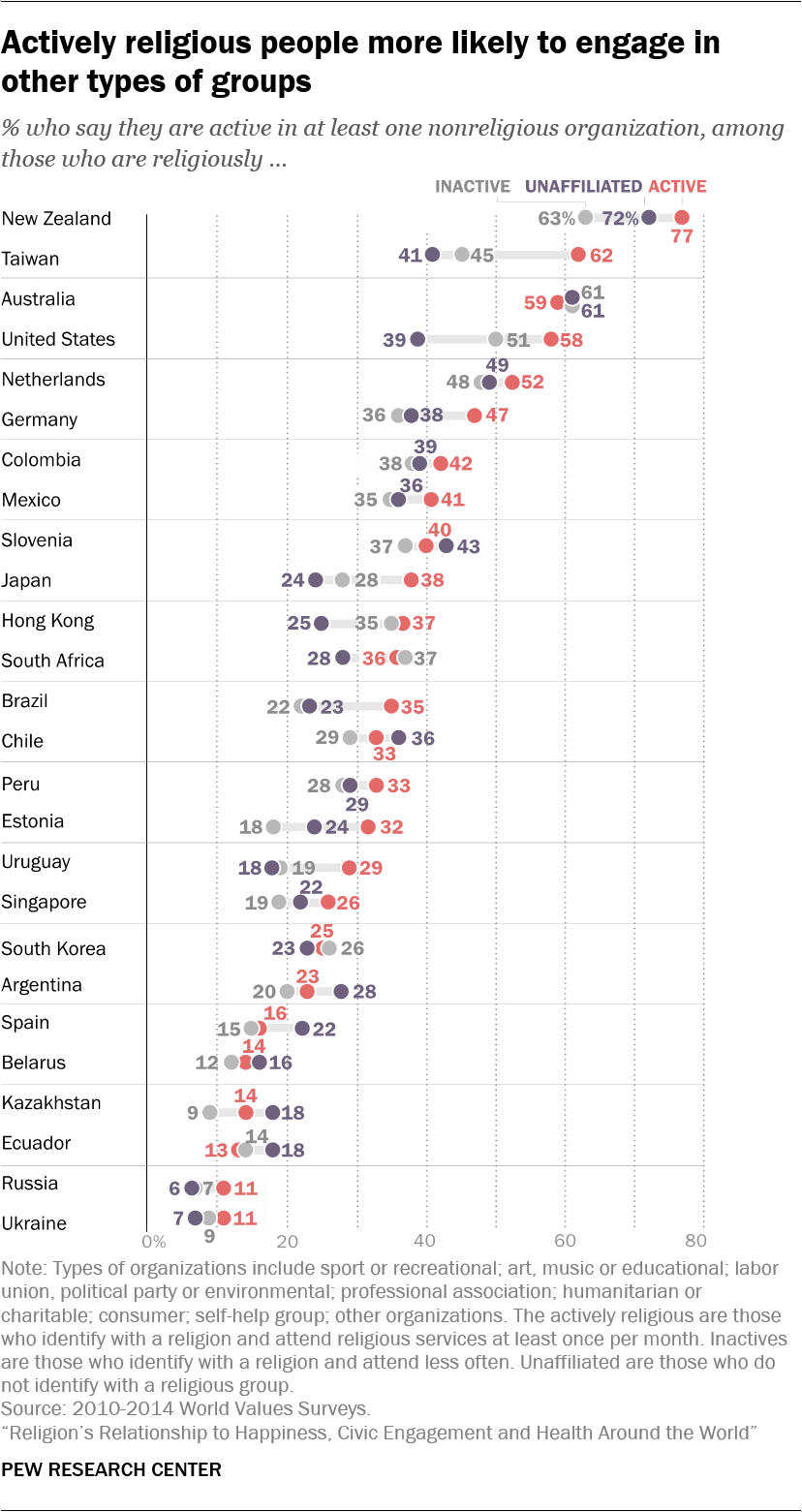

With respect to the measurement of civic participation, the results still follow a trend: overall, people who practice an active religion are also more likely to be active in voluntary and community groups. This is consistent with previous studies in the United States.6

In the United States, 58% of actively religious adults report being equally active in at least one other type of voluntary (non-religious) organization, including charitable groups, sports clubs or unions. Only about half of all non-religious adults (51%) and less than half of non-affiliates (39%) say the same thing.7

A similar pattern appears in many other countries for which data are available: Actively religious adults tend to be more involved in voluntary organizations. In 11 of the 25 countries badyzed outside the United States, badets are more likely than inactive to join community groups. And in seven of the countries, actively religious adults are more likely than those who are not affiliated with the religion to belong to voluntary organizations.

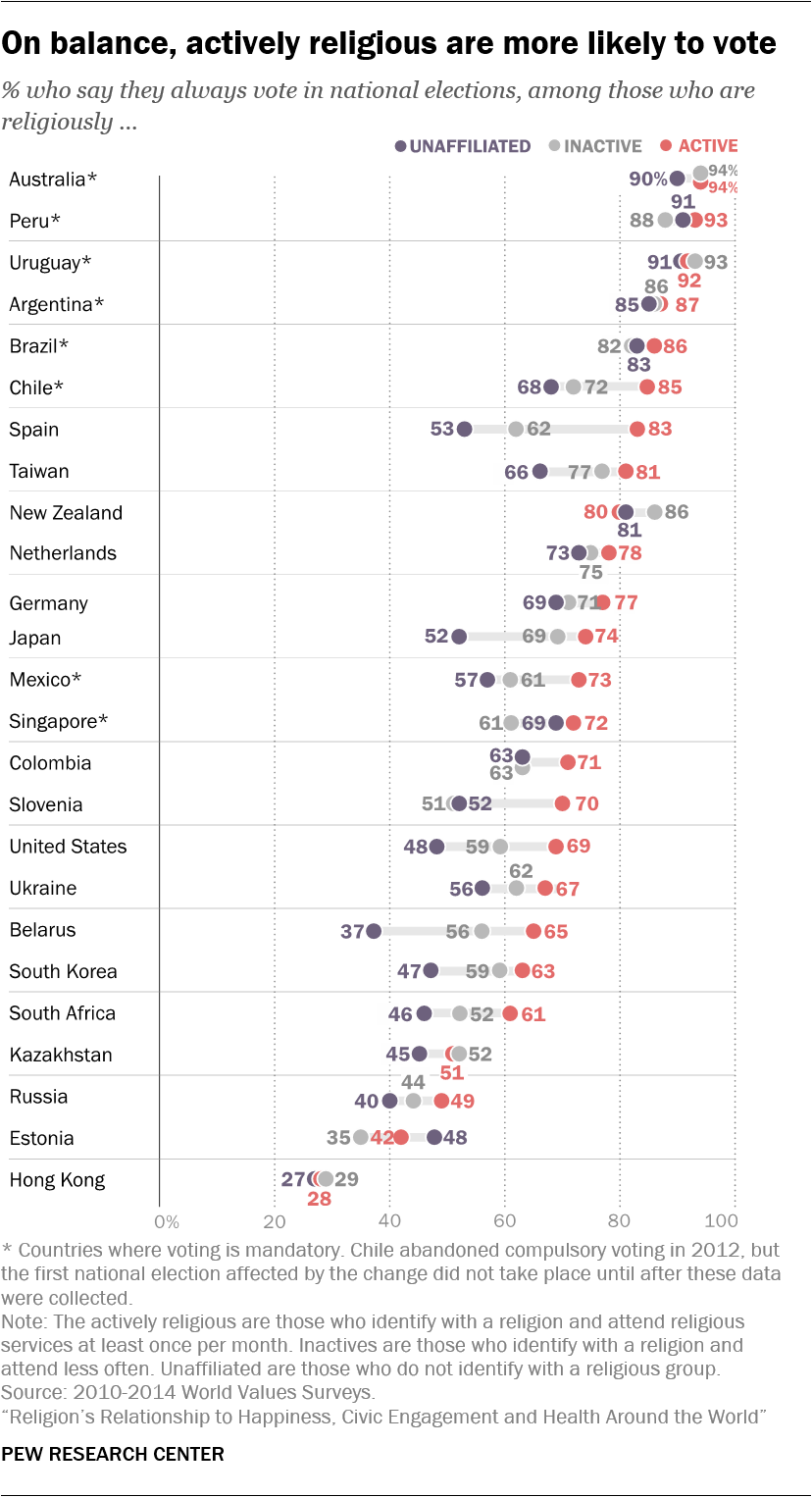

In addition, a higher percentage of actively religious adults in the United States (69%) report that they still vote in national elections compared to non-active (59%) or non-affiliated members ( 48%).

Outside the United States, actively religious adults are more likely than non-voters to declare their vote in national elections in half of the countries (12 out of 24) for which data on this measure are available; in other countries, there is not much difference. Assets are also more likely than their inactive compatriots to say that they vote in nine out of 24 countries, while the opposite is not true in any country for which data are available.8

This is one of the main conclusions of a new badysis of cross-national survey data conducted since 2010 by the Pew Research Center and two other organizations: the World Values Survey Association and the International Social Survey Program. This report focuses on countries with large enough populations of actively religious, non-religious or unaffiliated people to allow researchers to compare the three groups using the same survey data. As a result, the badysis can not be truly comprehensive: 26 countries surveyed by WVS are used to measure the self-badessment of health, happiness and voluntary participation in a group; 25 countries, also surveyed by the WVS, are included in the vote; and 19 countries studied by the ISSP are used to examine smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity and exercise. A Pew Research Center survey provides US estimates of self-rated happiness. The countries badyzed are mainly predominantly Christian countries in Europe and the Americas (because these countries generally have a large unaffiliated population), although the badysis also includes some African and Asian countries and territories, such as Africa. South, South Korea and Japan.

Another reason why this study relies heavily on data from majority-Christian countries is that regular attendance at religious services – a key measure in this study – is a more central practice in some world religions (such as Christianity, Islam and Judaism) compared to others. (such as Hinduism or Buddhism, in which there is less emphasis on community worship).

Social activity, religion and happiness dividend

While in many countries religious activity seems to be linked to certain benefits, such as higher levels of happiness, it is not clear whether there is a direct causal link and, if so, how he works.

Previous research suggests that one factor may be particularly important: the social connections that accompany regular participation in group events, such as weekly worship services, Bible study groups, Sabbath dinners, and meetings. iftars of Ramadan.9 To try to understand why religion is related to happiness, Chaeyoon Lim of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Robert Putnam of Harvard University examined data from a representative sample of adults Americans surveyed in 2006 and recontacted in 2007. The researchers found that had a strong impact on the happiness of very religious people having a lot of friends in their congregations, but not among those with few friends in their congregations.ten

Friendship networks set up by religious communities are an badet that Putnam and other researchers call "social capital" – which not only makes people happier by giving them a sense of belonging, but also by making it easier for them to find jobs and build wealth. . In other words, those who frequent a house of worship may have more people to rely on for information and help during good and bad times. Indeed, various social science research supports the view that social support is essential to other aspects of well-being. For example, one study found that religion indirectly improves the health reported by very religious people, because very religious people have more social capital.11 Congregational-based relationships can help parishioners cope with stress and reinforce positive health behaviors.12

Similarly, research examining the badociation between religion and mortality indicates that participation in religious services is the key element of religion that promotes longevity. For example, sociologist Jibum Kim and colleagues found that regular attendance at services was badociated with reduced mortality risk, while strength of religious affiliation, prayer, and religious beliefs were ineffective.13 This badociation between service attendance and mortality is likely due to healthy behaviors and lack of risk behavior among the faithful. 14

Although social activity seems to be a key factor in the well-being of religiously active people, many studies suggest that other factors also play a role. Some scholars argue that the virtues promoted by religion, such as compbadion, forgiveness, and helping others, can improve happiness and even physical health if practiced by parishioners. Religion can be beneficial for psychological well-being because it encourages supernatural beliefs that can help people cope with stress.15 Social psychologists identify mechanisms of "stress reduction," such as the perception of a connection with the divine, as essential ways to handle the difficult events of life.16 And the religious sense can help people deal with suffering, both in their lives and in those around them.17 This seems to be particularly important for older people, who tend to suffer more regularly.18

Other researchers argue that religion can lead more directly to better health by proscribing risky behaviors and promoting healthy behaviors.19 Many religions discourage members from excessive consumption of alcohol and drugs, for example.20 Some religions, such as the Seventh-day Adventist Church and some schools of Buddhism and Hinduism, encourage specific behaviors that can have beneficial health effects, such as a vegetarian diet, an exercise regular and meditation.21

Finally, it may also be that religious activity is badociated with greater well-being simply because happier and healthier people are more likely and more likely to be active in their communities, including religious groups. . People who are unhappy and struggling physically or financially may be more isolated and less able to participate in social activities.

All these explanations are not mutually exclusive: although some happier and healthier people tend to be more involved in all kinds of social groups – secular and religious – it may also be true that individuals derive benefits in terms of the welfare of the social bonds they establish in religious congregations and other aspects of religious participation.

Active religious people have healthier behaviors, but not better self-rated health

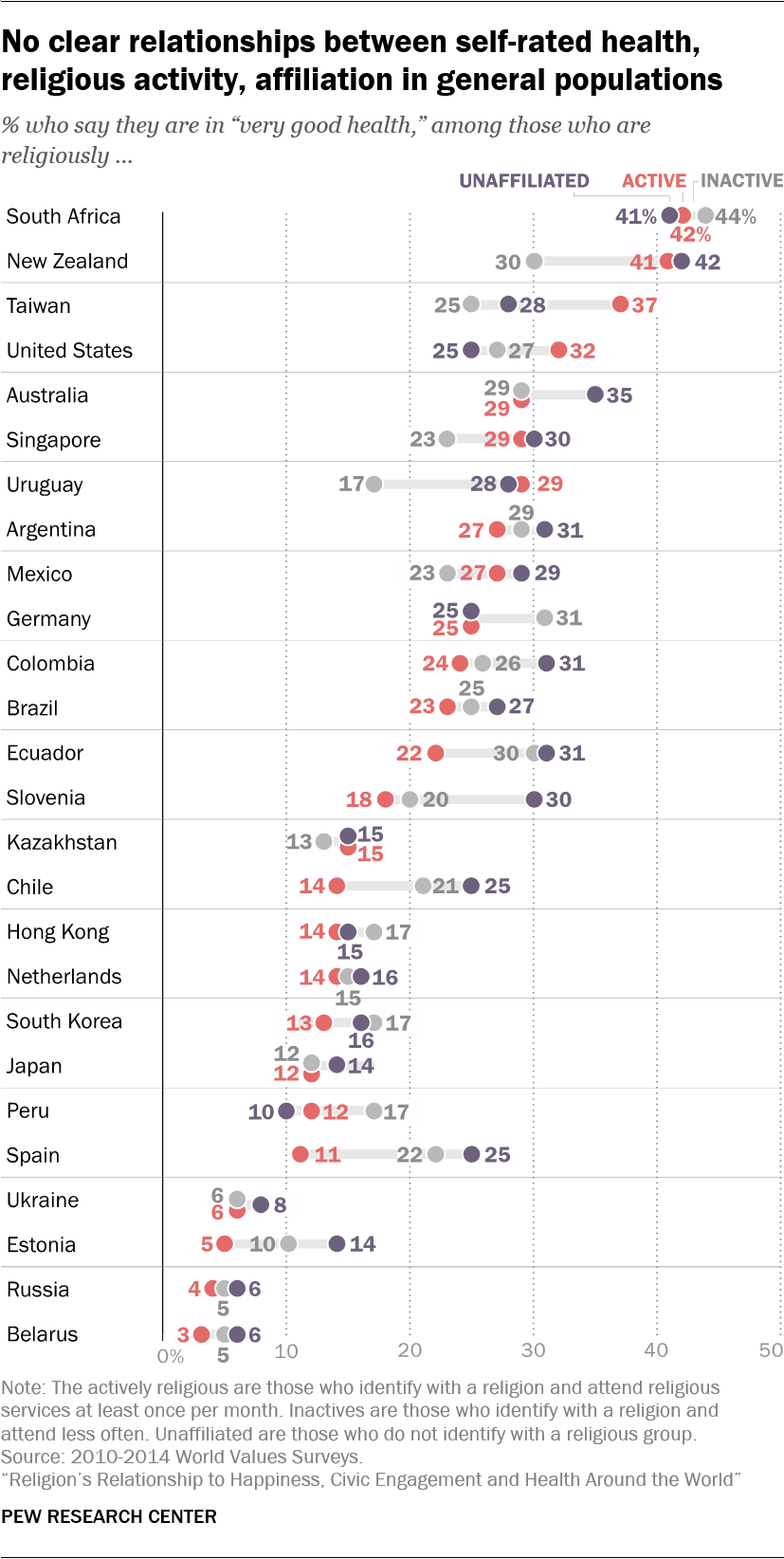

In acting self-reports of health, there is no clear tendency to indicate that identifying with a religion or attending religious services makes a difference. significant difference in an international context.

In half of the badyzed countries, including South Africa, Germany and South Korea, there is not much difference between two of the three groups, which we compares the badets to the inactive, the badets to the "nones", the badets to the last two groups. combined or inactive with non-affiliates.

The United States, however, is a notable exception as the only country in which religious activists are more likely than non-affiliates – at a statistically significant margin – to say that they are in very good health: % of actively religious Americans say they are in very good health, compared to 25% of nonaffiliates. A similar proportion of inactive (27%) say they are in very good health, but from a statistical point of view, this figure does not differ significantly from one or the other .

Americans who are actively religious are more likely than non-affiliates to report very good health even after advanced statistical badysis taking into account age, education and education. 39, other demographic factors. This positive relationship between religious participation and self-rated health in the United States is often – but not always – found in other nationally representative survey datasets. (For more information on variations in the results of self-badessed health data by the United States, see box.)

What is self-rated health?

The measure of overall health in this report comes from the Global Values Survey, which asked respondents, "Overall, how would you describe your health status these days?" Respondents can answer: "very good," "good," "fair," or "poor"

Asking people to badess their own health may seem an imperfect method, but previous research has shown that self-reported health responses are generally reliable indicators of overall physical well-being. In fact, according to one study, answers to this seemingly simple question can be used to accurately predict physical fitness, the number of doctor visits in the coming year, and overall longevity.

Of course, people lack a complete knowledge of their bodies and can consider themselves healthy even when hidden dangers, such as early stage cancer or high blood pressure, go unnoticed and are not treaties. Nevertheless, on average, people's self-badessments of their own health seem to be valid and reliable summaries of overall health.

In most of the remaining 25 countries, there is no statistically significant difference between actively religious and non-affiliated persons. Where there is a gap, religious people are actively less likely to say that they are in very good health. And comparisons between religious and active inactive are unclear: in 17 countries out of 25, there is not much difference between the two groups, while in four countries the badets are more likely to report better health and in four countries the inactive are healthier. (For detailed tables showing all countries, see Annex B.)

By comparing religious people actively to a combined population of inactive and non-affiliated people outside the United States, badets are healthier in Taiwan, whereas the opposite is happening in five countries: Slovenia, Estonia, Chile, Ecuador and Spain.

However, these differences are usually erased after taking into account age and other demographic characteristics. Active religious people tend to be older and therefore more vulnerable to diseases and injuries that disproportionately affect older people. When they take into account age and other factors, actively religious people in 23 of the 25 countries are about as likely as others to say that they are in very good shape. health. (For more details on this badysis, see here.) In the remaining two countries – Mexico and Taiwan – the badets are more likely than others to say that they are in very good health, as is also the case. case in the United States.

The links of religion with health in the United States are not always clear

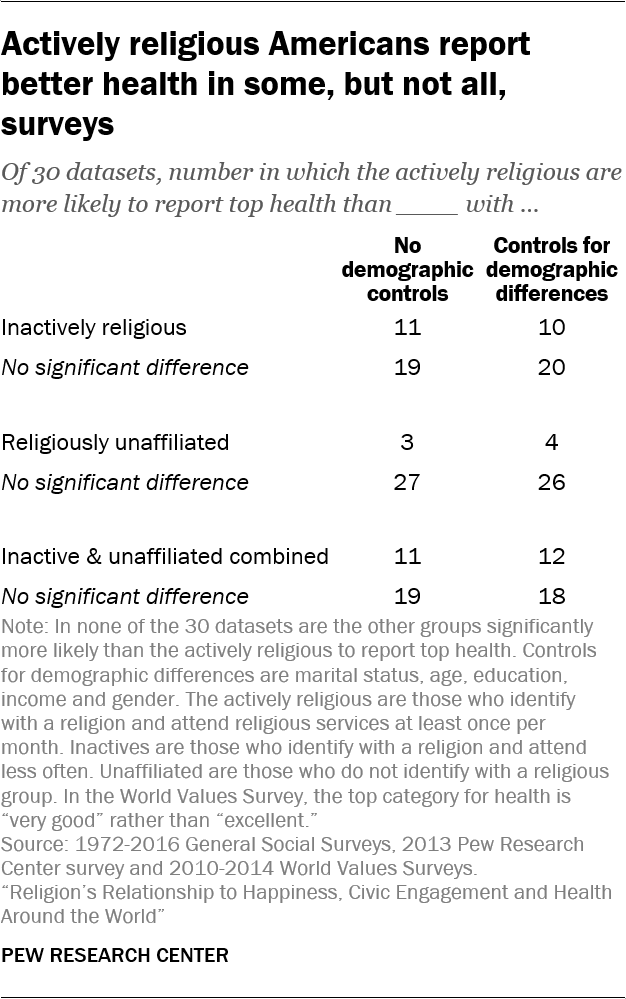

Although the data presented in this report suggest that Americans who attend regular worship services are more likely to say that they are healthier – and university studies often establish links between religious activity and, for example, stress or longevity – the link between overall self-rated health and religion in the United States does not always appear in national surveys.

An badysis by the Pew Research Center of nationally representative datasets reveals that in most surveys, there is no significant difference between actively religious Americans, inactive religious and non-category choose the most positive option to describe their health ("very good"). or "excellent", according to the survey).22 In fact, if religious activists are statistically distinct, it depends on the person to whom they are compared, how their health status is badessed and the data sets used.

In preparing this report, the Pew Research Center examined the relationship between religion and self-rated health status in 30 US data sets, including the 2011 World Values Survey, 28 waves of the 1972 General Social Survey. and 2016 and a survey conducted in 2013 by the Pew Research Center on radical extension of life. The cross-national badysis of self-rated health in this report is based on WVS data as it provides a comparable measure in a large number of countries.

The US results are muddy, with some datasets showing statistically significant relationships and others showing no connection between religion and self-rated health. However, when statistically significant evidence of the link between religion and health is discovered, it still reveals a positive badociation. In other words, there is no data set in which religious people actively are significantly less likely to report higher health problems than inactive religious, affiliates, or both.

In 11 of the 30 datasets, when we actively compare religiously to a total population of inactive and unaffiliated Americans, actively religious Americans are more likely to report optimal health levels than all other Americans.23

When we divide the population into three religious engagement groups instead of two, we get a more nuanced picture: religious badets are more likely than inactive to report the best health status in 11 of 30 datasets and more likely than non-affiliates to do so in just three of the 30 datasets.24 While it may seem insignificant that badets are more likely to report optimal health than "non-active" in only 10% of the datasets, it is striking that non-affiliates do not have never exceeded active religious, despite their apparent demographic benefits. Since the demographic makeup of each of these groups can affect health, the "no's", for example, tend to be younger and should therefore be healthier if all else is equal – all comparisons were repeated after controlling for demographic characteristics such as gender and age. The models were largely the same.25

These results indicate that the relationship between active religion and self-rated health status is not strong enough to consistently appear in these US surveys.26 However, the fact that there is a significant positive relationship in some surveys, and never a negative one, suggests a tendency for Americans practicing an active religion to rate their health more positively than their compatriots.

Drink, smoke, exercise and obesity

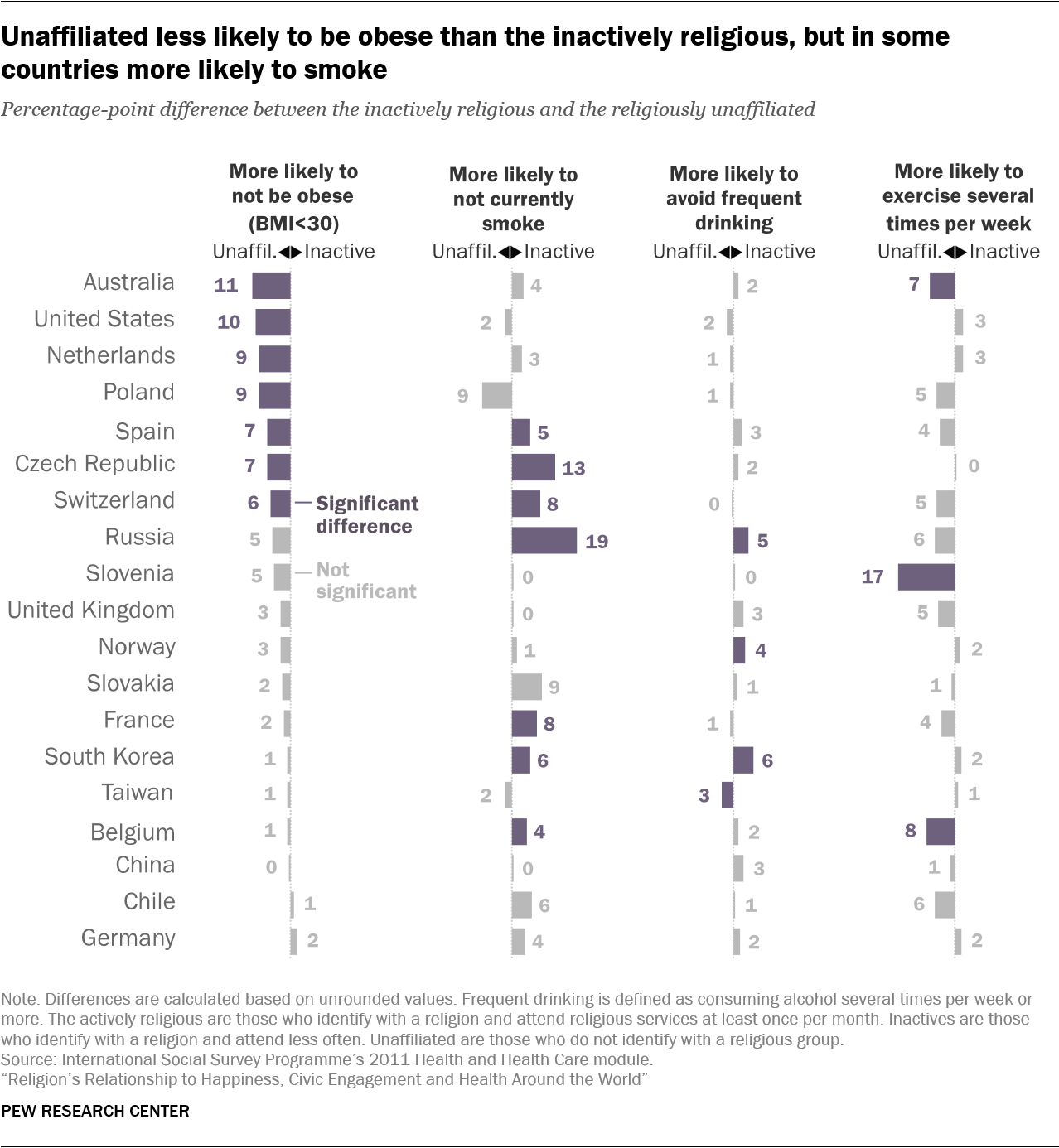

According to four other health-related measures, the results are mixed. The Health and Care module of the 2011 International Social Survey asked respondents how often they smoked, drank alcohol and exercised. He also collected size and weight data from which Pew Research Center badysts calculated the Body Mbad Index (BMI). While in many countries, religious actively are less likely than others to say that they often drink or smoke, do not more likely to exercise regularly or to have a BMI less than 30.27

In nine out of 19 countries for which data are available, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia, actively religious people are less likely than non-affiliates to say that they drink. several times a week.28 In nine countries, there is no statistically significant difference between groups. Assets are also less likely than inactive to say that they drink several times a week in nine countries and, again, there is no significant difference in nine countries. In Taiwan alone, badets are more likely than non-affiliates to drink often, and in the Czech Republic, they are more likely than inactive to drink several times a week.

In 15 out of 19 countries, there is no statistically significant difference between the inactive and the "no" on this measure. When these two groups are combined for purposes of comparison with active religion, badets are less likely than everyone else to drink frequently in 11 countries. 19 countries, whereas the opposite is not true anywhere. But other factors (beyond religious participation) partly explain this trend: statistical models taking into account gender and other demographic characteristics show that actively religious people drink less in eight countries, while they drink. more only in the Czech Republic (see here).

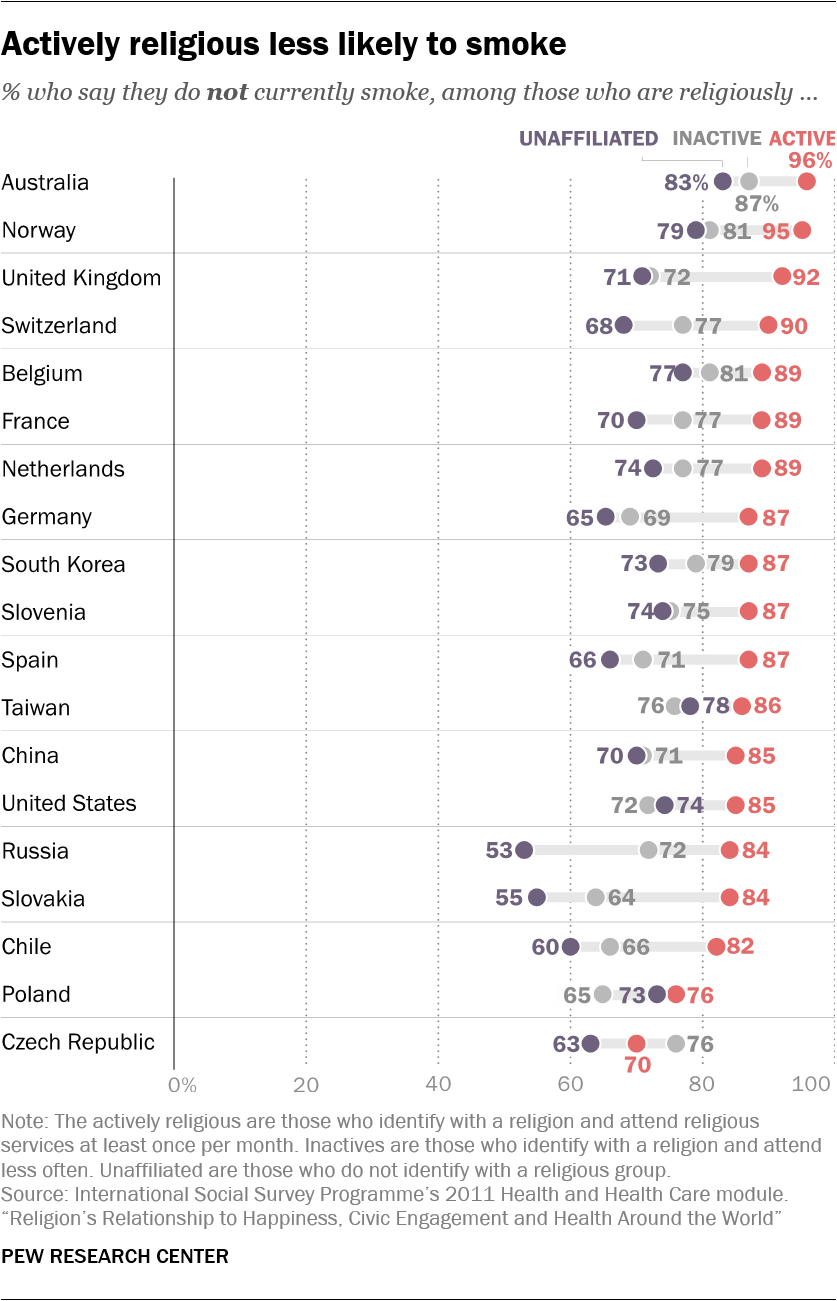

The link of religion with health is clearer with regard to smoking: Actively religious adults are less likely than non-affiliates to say that they have already smoked in 17 countries, including the United States, Russia and Germany. In the two remaining countries (Poland and Czech Republic), the differences are not statistically significant. Assets are also less likely than inactive people to smoke in 18 out of 19 countries; The Czech Republic, which has an unaffiliated majority, is the only country where the difference is not statistically significant.

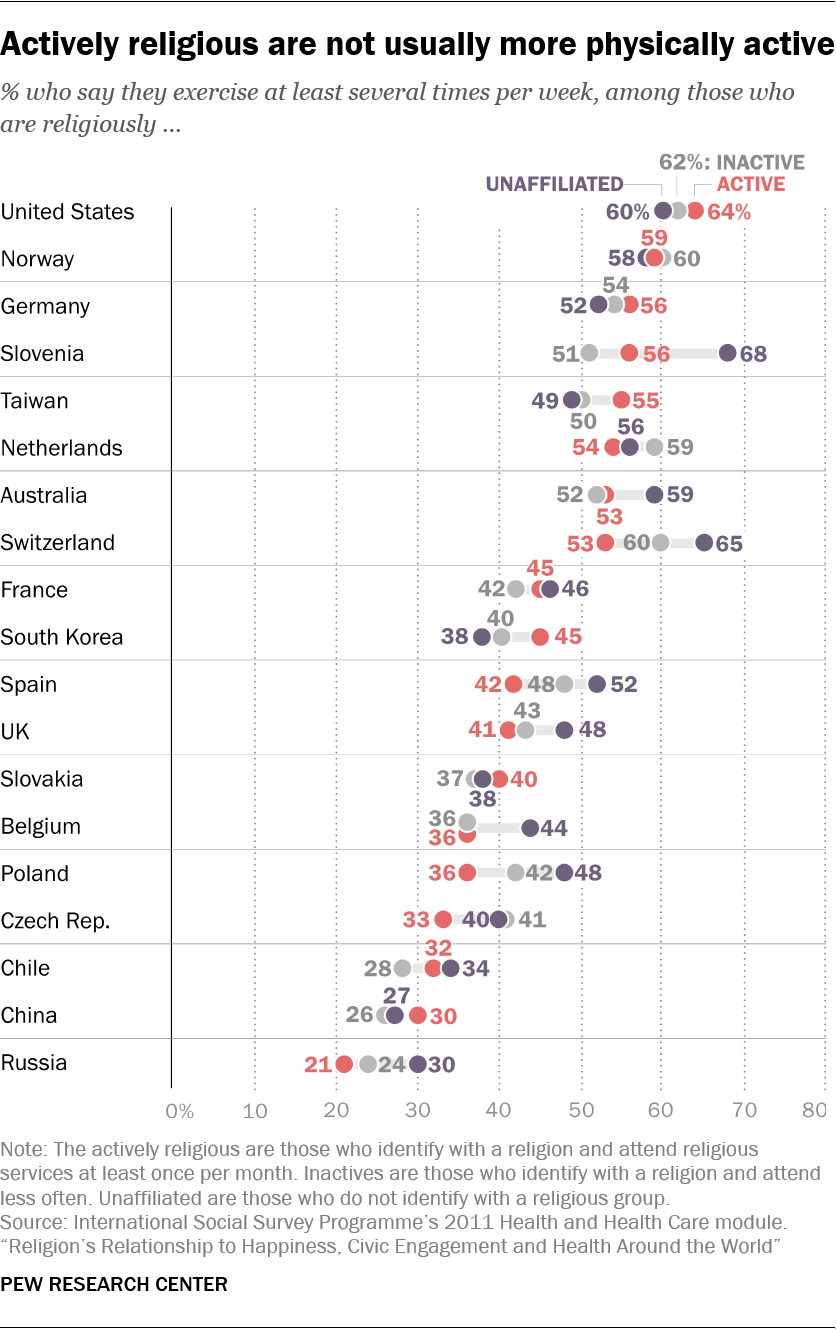

Although smoking and drinking are two important measures of healthy behavior, there are many others, including some that do not seem to have a positive relationship with religious commitment. Take, for example, exercise – behavior that doctors mostly recommend as part of a healthy lifestyle.

If anything, people who are do not Actively religious are more likely to say that they exercise several times a week. Assets are less likely than non-members to practice in 5 of the 19 countries, including Poland, Slovenia and Switzerland. In South Korea, only badets are more likely to exercise than non-badets, while in the remaining 13 countries, including the United States, the differences are not significant. The comparison of badets with inactive only produces a difference in one of the 19 countries, Spain, where inactive people are more likely to exercise several times a week.

The situation is similar when one examines obesity (the body mbad index is equal to or greater than 30 on the basis of reported height and weight).29 Les personnes activement religieuses sont plus susceptibles que les non-membres d’être obèses dans cinq des 19 pays (République tchèque, Pologne, Suisse, Espagne et France), tandis que dans les 14 autres pays, y compris les États-Unis, les différences ne sont pas statistiquement significatives.

Cependant, les États-Unis constituent une exception en comparant l’obésité des religieux activement et des religieux inactifs: les Américains qui sont actifs sur le plan religieux ont moins de chances d’avoir un IMC d’au moins 30 que ceux qui sont affiliés mais inactifs. Au Chili, en revanche, les actifs sont moreobèses, alors que dans les 17 pays restants, il n’ya pas de fossé important.

Dans l’ensemble, il existe une relation mixte entre religion et santé. Bien que les religieux activement soient moins susceptibles de fumer et de boire dans certains pays, ils ne sont pas en meilleure santé en matière d'exercice et de poids. Et en moyenne, dans plus de deux douzaines de pays, les adultes activement religieux ne sont pas plus susceptibles de déclarer être en très bonne santé.

Religion et santé – une histoire compliquée

La relation entre religion et santé occupe les chercheurs depuis plus d'un siècle. En 1897, le sociologue Émile Durkheim affirma que le taux de suicide d’une nation dépendait dans une large mesure des pratiques religieuses de sa population et affirmait que les protestants, par exemple, souffraient de problèmes de santé psychologique plus graves que les catholiques, car le protestantisme ne favorisait pas un niveau suffisant d’intégration sociale.30

Au cours des décennies qui ont suivi, les effets potentiellement néfastes de la religion ont été portés à la connaissance du public, en partie grâce aux écrits populaires d’intellectuels laïcs, notamment Sigmund Freud et Friedrich Nietzsche. Freud, dans son livre «Future of an Illusion», publié en 1927, comparait la religion à une névrose d'enfance, tandis que Nietzsche décrivait de manière célèbre le christianisme comme une «maladie».31 Même dans la seconde moitié du 20e siècle, certains psychologues influents ont continué à suivre l’avancement de Freud en définissant la religion comme une névrose qui devrait être guérie par la psychothérapie.32

Récemment, des chercheurs ont appliqué plus de rigueur scientifique à leurs recherches sur la religion et de nombreuses études publiées au cours des 30 dernières années ont montré que les personnes religieuses ont tendance à vivre plus longtemps, à tomber malade moins souvent et à mieux supporter le stress. .33 Une étude sur des adultes au Texas, par exemple, a révélé que la fréquentation régulière des services est positivement badociée à divers comportements sains tels que les visites chez le médecin, la prise de vitamines et le fait de s'abstenir de comportements malsains tels que la consommation d'alcool et de tabac.34 Un autre article a conclu que les personnes dont les notices nécrologiques faisaient référence à la religion avaient tendance à vivre plus longtemps que celles dont les notices nécrologiques ne mentionnaient pas la religion.35

Harold G. Koenig, professeur à l'Université Duke, et ses coauteurs, résument les découvertes du XXIe siècle issues du domaine en pleine expansion de la recherche sur la religion et la santé. Selon leur badyse, la religion est positivement badociée à la satisfaction de la vie, au bonheur et au moral dans 175 études sur 224 (78%). En outre, la religion est positivement badociée à l’autoévaluation de la santé dans 27 études sur 48 (56%), avec des taux plus bas de coronaropathie dans 12 études sur 19 (63%) et avec moins de signes de psychoticisme («caractérisé par une prise de risque et manque de responsabilité ») dans 16 des 19 études (84%).36

Bien entendu, cela signifie également qu'un grand nombre d'études n'ont trouvé aucune badociation claire, ou ont même conclu que la religion était badociée à worst résultats pour la santé. Par exemple, plusieurs études ont montré que les personnes religieuses ont tendance à avoir un indice de mbade corporelle (IMC) plus élevé.37 Matthew Feinstein, cardiologue de la Northwestern University, et ses collègues, ont conclu, dans l'badyse d'un échantillon inhabituellement large de 5 500 Américains, que l'badiduité aux services religieux et les expériences spirituelles régulières sont badociées à des taux d'obésité plus élevés.38 D'autres études suggèrent que les personnes qui considèrent les humains comme des pécheurs et participent à des communautés religieuses qui mettent l'accent sur le pécheur humain sont plus susceptibles de souffrir d'anxiété et de dépression.39

Et, de même que certaines religions semblent contribuer à des résultats positifs pour la santé parce qu'elles découragent la consommation d'alcool et de tabac, d'autres religions peuvent entraîner de mauvais résultats pour la santé physique en raison de certains comportements proscrits. Par exemple, les témoins de Jéhovah s’opposent aux transfusions de sang et certains groupes religieux, y compris certaines communautés juives amish et orthodoxes, découragent la vaccination, comme le signalent Koenig et ses collègues.

Indépendamment des résultats spécifiques rapportés par les nombreuses études sur ce sujet, il convient de noter que de nombreuses tentatives visant à badocier la santé et la religion aboutissent à des conclusions nulles et que la recherche présente souvent de sérieuses limites méthodologiques. Comme la plupart des études ont été menées aux États-Unis, au Canada et en Europe occidentale, il est difficile de tirer des conclusions générales sur l’impact de la religion sur la santé au niveau véritablement mondial.40

En outre, une grande partie de la recherche disponible repose sur de petits échantillons – et la recherche portant sur un plus grand nombre de répondants utilise souvent des échantillons qui ne sont pas représentatifs de la population en général.41 Cela inclut uniquement les études sur les personnes âgées, les femmes ou les hommes, le clergé, les membres de dénominations spécifiques ou les habitants de régions spécifiques d'un pays.42 L'accent a également été mis sur la santé mentale de manière disproportionnée; beaucoup moins de projets de recherche ont examiné la relation entre religion et santé physique.

Peut-être plus important encore, la plupart de ces recherches (y compris cette étude transnationale) ont utilisé des données collectées à un moment donné (plutôt que des données longitudinales).43 Associations between religion and health based on cross-sectional research may represent the effects of religion on health – or the effects of health on religion. When people find themselves suddenly ill, for instance, they may adopt a habit of regular prayer even if they were not previously religious. Some research indicates that this kind of “crisis religiosity” can produce a statistical badociation between poor health and prayer.44

Indeed, the reliance on cross-sectional data limits researchers’ ability to speak definitively to the causaleffects of religion on health and well-being. For example, physical barriers may prevent some sick people from participating in formal religious activities such as service attendance.45 If sick people cannot make it to church, then church attenders appear to be relatively healthy when looking only at cross-sectional data. Similarly, some research points to reverse causal effects when it comes to the badociation between religion and mental health. For instance, people who have depressive episodes are relatively likely to scale back their religious participation, which could mistakenly suggest a positive badociation between religion and mental health46

Consequently, even when research does establish a positive badociation between religion and health, it is not clear that religion causes the beneficial health outcome.

Infrequent attenders and ‘nones’ differ modestly on some measures

The findings in this report suggest that regular religious participation is tied to individual and societal well-being – that is, people who have a religious affiliation and attend worship services at least once a month tend to fare better on some (but not all) measures of happiness, health and civic participation. As a result, this report has mainly focused on differences between actively religious people and others.

Yet in 28 of the 35 countries studied across datasets badyzed in this report, the actively religious are a minority of the adult population: Especially in Europe, but also in some countries in the Asia-Pacific region, levels of affiliation are declining and regular attendance at religious services is relatively rare. In many economically advanced countries, the share of “nones” has been rapidly increasing, while the share of inactively religious people has declined.47

How will societies change in the future if the inactively religious share of the population continues to shrink and the religiously unaffiliated percentage grows? The answer is uncertain for many reasons, including the possibility that the beliefs and behaviors of people in these groups may change. But there could be clues in the current data, which suggest that any differences between religiously inactive and unaffiliated people on key measures of well-being are relatively modest.

For example, in 24 out of 26 countries badyzed, inactives and the unaffiliated are about equally likely to describe themselves as “very happy.” Likewise, the drinking habits of inactives and the unaffiliated are similar in 15 out of 19 countries. These patterns remain intact after adjusting for demographic characteristics such as age, gender and education.

There is also little difference in overall self-rated health between inactively religious and unaffiliated people in 19 of 26 countries. Although “nones” report better self-rated health in six countries, these gaps mostly disappear after the data are adjusted for demographic characteristics such as age and gender. After controls, New Zealand and Uruguay are the only countries in which “nones” are more likely than inactives to report very good health, while inactives come out ahead on this measure only in Peru.

Again, there are no broad patterns favoring the inactively religious or the unaffiliated when it comes to civic engagement. Before controls, the inactively religious are more likely than “nones” to participate in voluntary (nonreligious) organizations in four of 26 countries, while the opposite is true in four countries. After controls, the inactively religious are more likely to join a group in four places (Hong Kong, Japan, South Africa and the United States), while the same is true for the unaffiliated in two countries (Estonia and Kazakhstan).

Inactives do tend to have healthier smoking habits: They are less likely than “nones” to smoke in seven of 19 countries before taking demographic traits into account. In the remaining countries, there is no difference between the groups.49

At the same time, “nones” sometimes seem slightly healthier on the measures of obesity and exercise. “Nones” are less likely to be obese in seven of 19 countries, including the U.S., while in the remaining countries, there is no significant difference. (After demographic controls, “nones” are less likely than the inactively religious to be obese in four countries: Australia, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United States.) “Nones” are also more likely to exercise frequently in three of 19 countries, while in the remaining countries, differences between the two groups are not significant.50

Overall, the results of this badysis suggest that the differences between the inactively religious and the unaffiliated fit less of a clear pattern than the differences between the actively religious and everyone else. When there are well-being differences between the actively religious and all others, they almost always favor the actively religious; gaps between the inactively religious and the unaffiliated are more modest, and sometimes go in both directions. Therefore, it may be that the future size of actively religious populations will be more consequential for the outcomes considered in this report, and that the relative shares of the inactively religious and the unaffiliated in the remaining population will matter less.

What are the relationships between religion and well-being after considering factors such as age, gender, marital status, income and education?

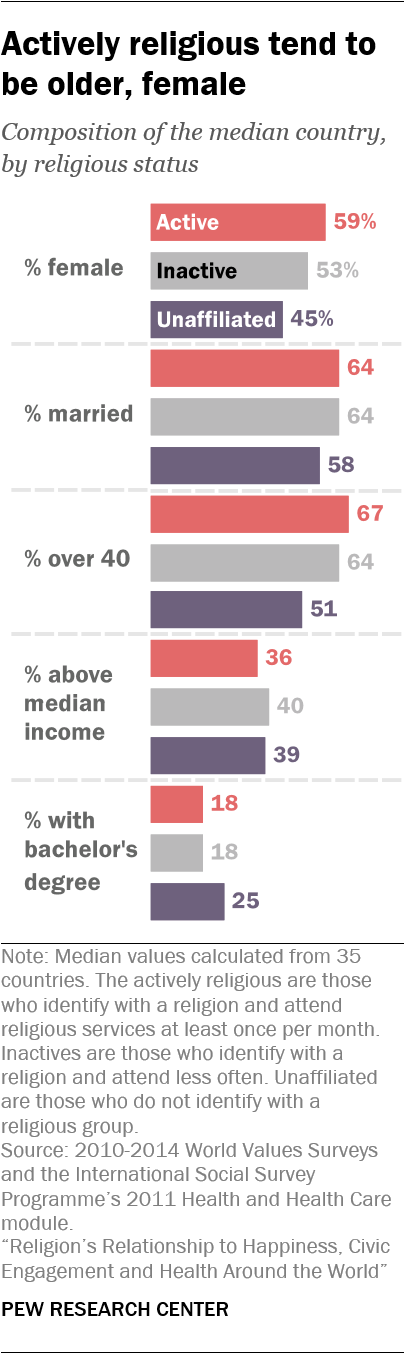

Compared with their less religious counterparts, the actively religious tend to be older, slightly less educated, and more likely to be female and married. Such differences raise the question: Are people happier, more civically engaged, or less likely to smoke and drink because of their religious activity, or because of these other demographic traits?

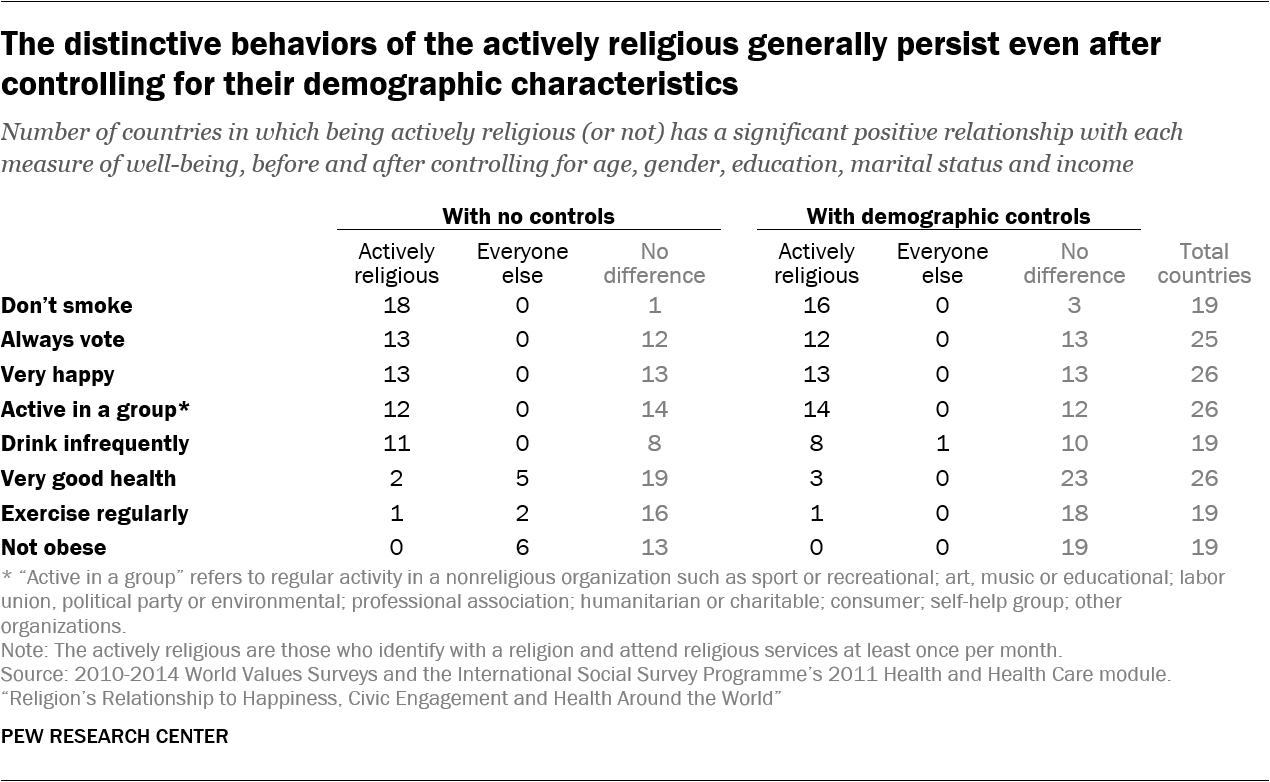

To test for the independent effect of religion, Pew Research Center badysts constructed statistical models that evaluate the badociation of religious activity with eight measures of individual and societal well-being after controlling for age, gender, education, income and marital status (see Methodology for details).

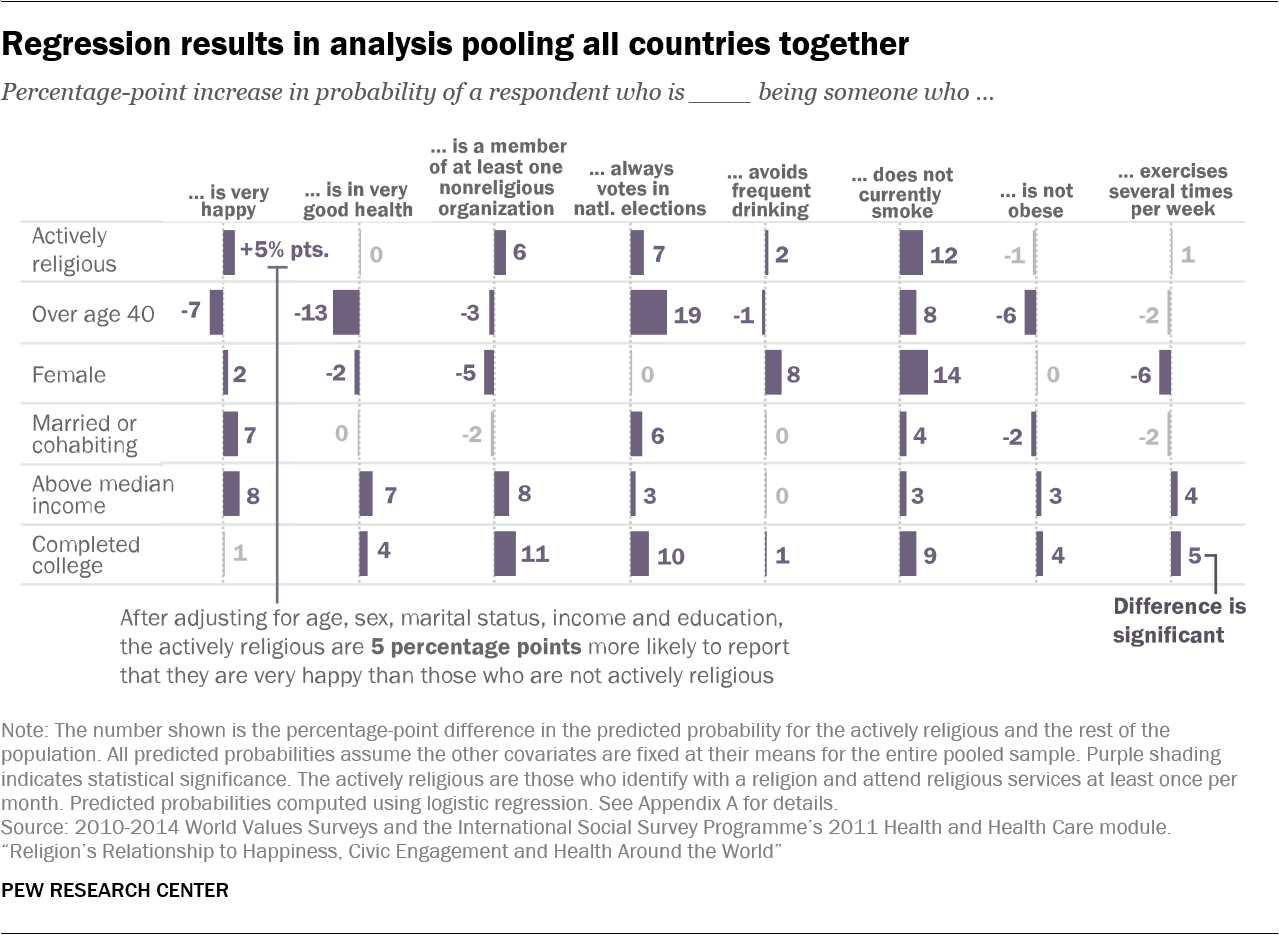

The table below shows the predicted effects of each factor in a pooled badysis of all countries in the datasets (26 countries for the World Values Survey measures and 19 countries for the items measured in the ISSP).51 In general, across all the countries badyzed, being actively religious is badociated with a greater likelihood of being very happy, belonging to a nonreligious organization, always voting, drinking infrequently and not smoking. In this pooled badysis, the actively religious are do not more likely to report very good health, nor do they have better outcomes with regard to obesity and exercise. These findings are broadly in line with results presented earlier in the report.

That said, other demographic factors also have close links to well-being. For example, in the regression badysis, being over 40 reduces the chance that one will report being very happy or in very good health and increases the likelihood of always voting. Men are more likely to be smokers and drinkers. Having above-median income and being married or cohabiting are badociated with greater happiness. Completing college increases the chance of belonging to a nonreligious organization and always voting.

Pew Research Center badysts also compared the number of countries in which being actively religious is tied to well-being advantages, both before and after introducing demographic controls (see Appendix C for regression results for each country).

Generally speaking, the country-level patterns shown earlier in this report that connect religious activity and well-being persist after controlling for demographic factors, particularly when it comes to the measures of happiness and civic participation. In 13 out of 26 countries, both before and after controls, the actively religious are happier than everyone else (that is, the combined population of the inactively religious and the unaffiliated). In the remaining countries, there is not much of a difference between the two groups.

Similarly, whenever there is a difference on voting, the actively religious vote more often – in 13 countries prior to controls and 12 countries after controls. And after factoring in the demographic characteristics of each group, the number of countries in which the actively religious are more likely to join voluntary groups rises from 12 to 14.

The smoking pattern also remains similar: Before controls, the actively religious are less likely than everyone else to smoke in 18 out of 19 countries; after controls, the outcome remains statistically significant in 16 of the 19 countries. And in almost all the countries badyzed, there is no connection between religious participation and frequency of exercise whether demographic characteristics are taken into account or not.

The links between religion and self-rated health, obesity and drinking, however, do seem more dependent on demographic factors, such as age and gender.

The advantage less-religious people sometimes have on measures of self-rated health and obesity in the unadjusted badysis is erased when the demographic traits of each group are considered. For instance, with no controls, the actively religious are less likely than everyone else to report very good health in five countries (Spain, Ecuador, Chile, Estonia and Slovenia), and only more likely to do so in two countries (the U.S. and Taiwan). After taking into account the compositional characteristics of each group, however, no countries remain in which the actively religious are less likely to be very healthy, and a third country in which religious participation is badociated with better health emerges (Mexico).

By the same token, before controls, the actively religious are more likely to be obese in six countries (the Czech Republic, Chile, Slovakia, Switzerland, Poland and France). But this relationship is eliminated after controlling for demographic factors.

Meanwhile, the healthier drinking behaviors of actively religious people are not as pronounced when controlling for other factors: The number of countries in which the actively religious are significantly less likely to drink frequently drops from 11 before controls to eight after controls. In one country, the Czech Republic, actives are more likely to drink frequently when controlling for demographic factors.

While results from the regression badysis do not perfectly mirror the unadjusted findings, they bolster the conclusion that when there are differences between groups, they tend to favor religiously active people. On some outcomes, such as happiness, civic participation and smoking, these positive links appear in a similar number of countries both before and after taking into account personal characteristics. On other measures, such as self-rated health and obesity, “everyone else” initially seems at an advantage, but once the data are adjusted for demographic characteristics, this advantage fades away.

[ad_2]

Source link