[ad_1]

In my childhood, I often remember many lazy summer days spent lugging my purple Huffy bike through the cement dunes of my suburban neighborhood. After the parade of my two older brothers and my neighbor, I often found myself facing hills that turned my palms into sweat. Looking gently at my brother then the steep slope, telling me, "Well, there's only one way to go," I would stubbornly proclaim "You're going first." He would take a look at the awesome hill, then look at Dylan, our neighbor. and suggests, "You go, so I'll go."

Dylan has always been there.

It almost always ended with great joy and a thumbs-up sign.

Then my brother left. Then I went, my previous scruples were soon replaced by "Hey, wait UP !!"

Years later, in a behavioral science clbad, I discovered an explanation for this. Humans are naturally reluctant to take risks, it takes X number of people who engage in a given activity to be able to engage in this activity. For the Dylan of the world, that number is 0. For some people, it is incredibly high, forcing a lot of people to do something before they participate, that is, they have very fear of risk. For some people, they may simply be risk neutral, sitting somewhere at the median.

This underlying principle governs almost all aspects of human behavior and interactions, from scabby-knee getaways to social upheaval. In economics and finance, the application is clear. During the uprisings of the 2010 Arab Spring, it was first necessary for Mohamed Bouazizi's self-immolation to stir up demonstrations in Tunisia, which provoked uprisings throughout the Middle East, while more and more people were revolting.

In the Moroccan province of Al Haouz, the community is waiting patiently to see the result of a farmer's decision to move from farming to the more lucrative (and sustainable) crop of hectares of carob, almond and organic pomegranate. If he harvests the fruit, literally, the rest of the community will follow his example, ignoring the farming practices that have been commonplace for generations.

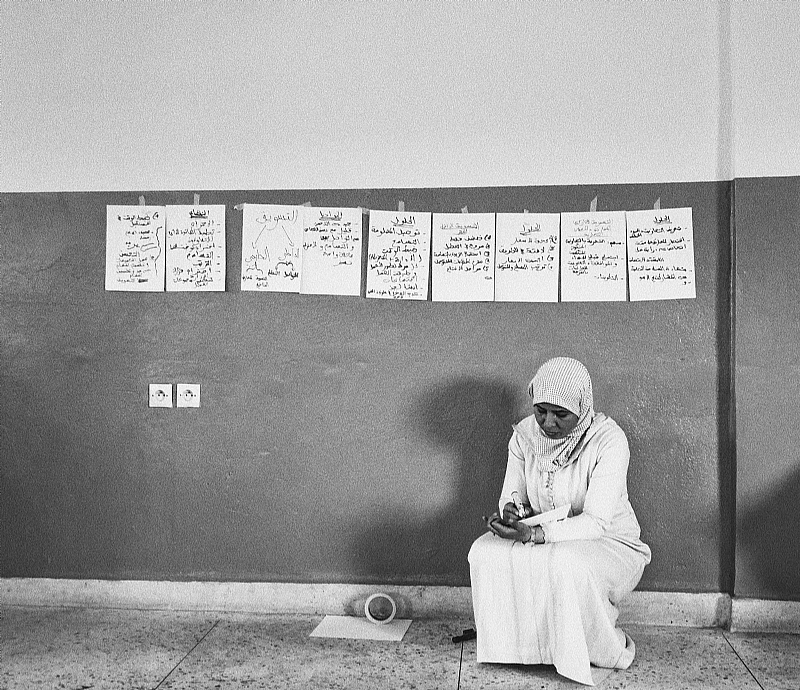

For Amina Al Hajjami, a women's empowerment trainer and High Atlas Foundation project leader, the course of her life was changed by her father's decision to send her to school. She was the first girl in her community to go to school. Some have called his father crazy. Yet, Amina was traveling four kilometers every day to get to school, never missing once. Today, her younger sisters and the majority of girls in her community go to school. Amina now runs workshops on women's empowerment and has trained more than 600 women in empowerment. None of this would have been possible if his father had not chosen to break the old traditional values of his community.

In underdeveloped communities, it's hard to understand why it's obviously not right to send your daughter to school or to go organic. But years and years of customs and cultural norms forge a rigid school of thought, long applied by the compliance of generation to generation. It is difficult for someone who is far from the place to understand this, and it is certainly much easier to write as a consequence of "impoverishment" or "rural" . But doing so would be inherently inaccurate.

The best way to realize the benefits of an action is to make it happen. The best way to really listen is to hear it from one of your own. It's one thing to preach about the great benefit of planting organic fruit trees, but it's another thing to see a community member follow the process and take advantage of it. Thanks to this snowball effect, deep and lasting changes can be made, new traditions can be forged and local development can be achieved.

We often tend to view cyclical endogenous development issues as religious or cultural, but there is an inevitable inaccuracy when we generalize people to the larger systems in place. Forgetting that a culture is made of millions of people, like you and me, filled with fears, hopes and worries. Being human means being opposed to change, being afraid. We are attracted by the familiar, the tried and trusted, it is often not a question of ignorance or oppression.

After all, sometimes we need Dylan's will before making an act of faith.

Sarita Mehta is a student in economics and politics at the University of Virginia. She is currently a development trainee at the High Atlas Foundation in Morocco, where she is studying women's empowerment and participatory development in the context of Islam.

Warning: "The views / contents expressed in this article only imply that the responsibility of the authors) and do not necessarily reflect those of modern Ghana. Modern Ghana can not be held responsible for inaccurate or incorrect statements contained in this article. "

Source link