[ad_1]

One of the basic myths of the modern economy is that central banks are independent and able to conduct monetary policy without suffering the pressures of politics. This makes monetary policy more efficient: it suggests that the economy will be maintained on a stable trajectory, unaffected by the demands of the electoral cycle.

President Donald Trump undermines the credibility of this precious myth. How far can he interfere in the US Federal Reserve before the myth is seriously devalued?

The subtlety of this problem has been demonstrated in recent months. The Fed raised interest rates in December despite the clear opposition of the president. The Fed's open market committee knew that its actions would offend Trump, but members had little choice. Throughout 2018, the Committee had indicated its intentions through "forward-looking forecasts", with a specific forecast of four rate increases during the year.

Independence, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder, or in this case, the skeptical judgment of unstable financial markets.

Thus, missing the fourth increase in December would be to announce a return to the Arthur Burns / Richard Nixon era, when Burns, then president of the Fed, had the task of carrying out all that Nixon would deem necessary to facilitate – election. The result was the inflation of the 1970s, interrupted only by the painful 1979 Volcker Shock (Can the Fed resist Trump's pressure?)

After December, Trump had been silent, at least on this subject. This gave the committee the opportunity to use its March meeting to restore the political environment. No change in the federal funds rate had been expected, too, leaving the key rate unchanged was not a surprise. But the guidance in front of the "dot chart" has been reset, the masterful inertia being the word of order this year. In addition, the slowdown in quantitative easing (QE) will be slowed down and then halted.

The immediate risk of a confrontation with the president that undermined the country's independence was postponed. At the same time, the risk of loss of credibility of the Fed through a too strict policy has been reduced. The Fed's independence is being maintained for the moment.

Now, Trump has reiterated his criticism, accusing the Fed of not having an even stronger economy. He calls for expansionist QE to be resumed. Two names of potential new members of the Committee are now circulating – both with very close links to the President and none with a thorough knowledge of monetary policy.

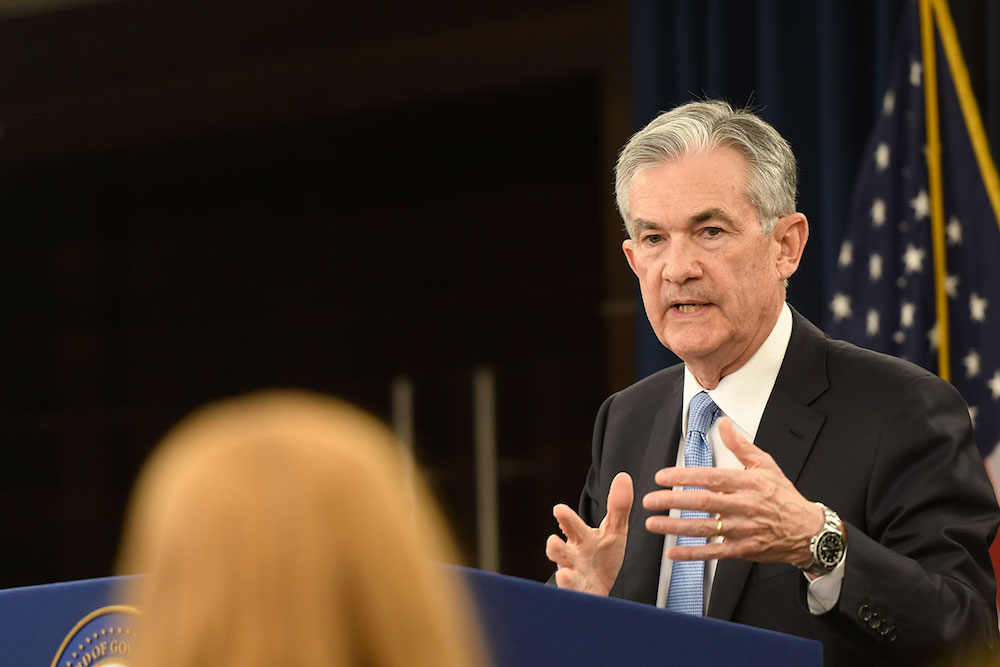

It is unlikely that Trump will expect Fed Chairman Jay Powell to succumb to and quickly lower the key rate or resume an expansionary QE: going into history like another Arthur Burns would be too humiliating. But if this kind of active criticism becomes the norm (as its economic adviser Larry Kudlow claims, this should be the case), then resignation could be a serious option for a besieged president at some point.

This would give Trump the opportunity to make a second attempt to appoint a flexible president. Depending on who was chosen, this could turn the Fed into another instrument of Trump's unique economic policy.

Independence, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder, or in this case, the skeptical judgment of unstable financial markets. Three key elements influence the judgment: the appointment of the main central bankers; the decision-making process for monetary policy; and the political skill of the president.

Central banks can not be independent in the sense of autonomous institutions, they are free to do what they want and to choose their own leaders. Governments always have the right to appoint the best central bankers. This is just an established precedent, a public review, and in the United States, the congressional confirmation process ensures that appointees will be technically competent and politically neutral, rather than flexible.

Although the US presidents have a policy of appointing people of their own political persuasion, they have almost always chosen a highly qualified economist as president. Jay Powell, the appointment of Trump, was an exception: he was a lawyer but had been part of the open market committee since 2012. The markets would not comfort the two new candidates, whose main qualification is perceived as a proximity with Trump.

An operational rule – such as targeting inflation – provides a decision-making framework that can withstand political pressures. The Fed has an inflation target, but its model is the most flexible, its mandate giving as much weight to unemployment as to inflation. This leaves more room for subjective judgment – enough to meet the political objectives.

This leaves the president with an essentially political task: to demonstrate his willingness to resist, if necessary, the wishes of politicians, without being provocative enough to lose his job. That's the task Powell is now facing.

Former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan provides the template. His reputation has been severely tarnished by the 2008 crisis, but his track record is second to none as an accomplished, cheerful and outspoken political operator of Washington's politicians and opinion makers. Greenspan dominated the Committee, debating politely but firmly with all the divergent points of view.

Powell will have a hard time baduming the role of "Maestro" by Greenspan, as it comes from decades spent looking at the insides of esoteric economic data. But let's hope Powell can pick up some of the political technique.

Source link