[ad_1]

It was well before noon, but Beyenesh Tekleyohannes’ house had already been buzzing for hours: more than 30 guests were singing, praying and sharing plates of shiro and lentil stew in honor of a great Orthodox Christian holiday.

The atmosphere on that November day was so lively that no one noticed Eritrean troops approaching on foot the winding dirt road leading to Dengolat, a village in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia, until it’s too late.

Dressed in military uniforms and speaking in an Eritrean dialect of the Tigrinya language, the soldiers forced all the guests in, tore off the men and boys, and led them to a patch of sunburned land down the hill. .

Beyenesh heard the first shots as she fled in the opposite direction to safety, and immediately feared the worst for her male relatives downstairs: her husband, two grown sons and two nephews.

When she emerged from her hiding place three days later, Beyenesh discovered that the five had perished in the massacre.

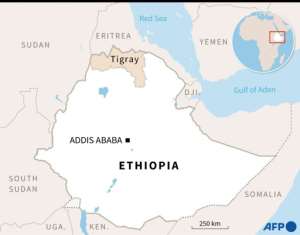

Map showing the Tigray region in Ethiopia. By Aude GENET (AFP / File)

Map showing the Tigray region in Ethiopia. By Aude GENET (AFP / File) The soldiers tied their hands with belts and ropes and shot them in the head.

“I’d rather die than have lived to see this,” Beyenesh told AFP, tears streaming down her face as she described how the annual St. Mary’s festival turned into a bloodbath.

Local church officials say 164 civilians were killed in Dengolat, with most of the deaths occurring on November 30, a day after the festival.

This makes it one of the worst atrocities known in the ongoing conflict in Tigray.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s government severely restricted humanitarian and media access to the region, and for nearly three months, the people of Dengolat despaired of sharing their story with the world.

AFP arrived in Dengolat last week, interviewing survivors and looking at mass graves that now dot the village, a cluster of stone houses surrounded by the steep rocky escarpments of Tigray.

Local church officials say 164 civilians were killed in Dengolat on the day of the attack on Beyenesh Tekleyohannes’ house. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP)

Local church officials say 164 civilians were killed in Dengolat on the day of the attack on Beyenesh Tekleyohannes’ house. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP) Human rights groups fear that instead of an extreme example of violence in Tigray, what happened in Dengolat could be worrying.

“There are so many places of violence and massacres in Tigray. The full extent remains to be known,” said Fisseha Tekle, Ethiopian researcher at Amnesty International.

“That is why we are calling for a UN-led investigation. Details of the atrocities must be disclosed and accountability must follow.”

So far, only Addis Ababa has said it is investigating “alleged crimes” in the region.

Make no mistake about Eritreans

Abiy – who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 – announced military operations in Tigray four weeks before the festival, saying they came in response to attacks by Tigray’s longtime ruling party on the camps of the federal army.

The powerful Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) has dominated Ethiopian politics for decades, and tensions soared with Abiy after taking office in 2018 and was accused of sidelining the party. .

As the war continues and reports of atrocities increase, soldiers in neighboring Eritrea, who largely support Ethiopian troops, are often seen as the culprits.

Addis Ababa and Asmara deny the presence of the Eritrean army in Tigray.

Last week, Amnesty released a report detailing how Eritrean troops “systematically killed hundreds of unarmed civilians” in the Tigray town of Axum, also in November 2020.

Tamrat Kidanu said he stood still after being shot when he heard Eritrean troops slaughter his son and other men in Dengolat. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP)

Tamrat Kidanu said he stood still after being shot when he heard Eritrean troops slaughter his son and other men in Dengolat. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP) Tigrayans from both places said there was no doubt about the nationality of the perpetrators: in addition to their accents, they cited facial scars specific to the Ben Amir ethnic group in Eritrea.

Tamrat Kidanu, a survivor of Dengolat, 66, told AFP he was walking to his corn fields the morning the Eritreans arrived and was shot in the right thigh.

Unable to move, he lay down on the ground and listened to soldiers mowing down other men, including his recently married 26-year-old son.

Two decades ago, when the TPLF dominated the central government, Eritrea and Ethiopia waged a brutal border war that left tens of thousands of people dead.

Many Tigrayans, including Tamrat, view the current conduct of Eritrean soldiers as a form of revenge.

“This kind of crime is to exterminate us, to humiliate us,” Tamrat said from his hospital bed in the regional capital Mekele, where he is unable to sit up without the help of a rope.

Church under fire

As Eritrean soldiers fired at men in central Dengolat, hundreds of other civilians huddled in terror in a centuries-old Orthodox church in the mountains.

However, the soldiers quickly warned that the church would be bombed if the men did not come out and surrender.

Some tried to flee higher into the mountains, but Eritrean soldiers shot them dead before they could get very far.

Dengolat men covered their faces to cry as the women beat the ground and showed pictures of their loved ones. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP)

Dengolat men covered their faces to cry as the women beat the ground and showed pictures of their loved ones. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP) Gebremariam, 30, who asked for his name to be changed for fear of reprisal, was among the few who surrendered to the Eritreans.

He was tasked with helping bury the dead, transporting the bodies – heads cut open by bullets – on a makeshift stretcher to mass graves.

Standing in front of one of the sites, located behind a cluster of cacti, Gebremariam scoffed at officials’ claims that the conflict had resulted in minimal civilian damage.

“What you see in front of you proves that it is a lie,” he said.

‘You need to talk’

The people of Dengolat had little opportunity to tell the story of the massacre.

After the Eritrean soldiers left, Gebremariam and other residents of Dengolat painted some of the stones marking the mass graves a bright sky blue.

“We thought maybe a satellite could see them that way,” Gebremariam said.

Ethiopian Orthodox priest Kahsu Gebrehiwot says the failure of church leaders to speak out may be a sign that they fear for their own lives. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP)

Ethiopian Orthodox priest Kahsu Gebrehiwot says the failure of church leaders to speak out may be a sign that they fear for their own lives. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP) When a team of AFP journalists arrived in the village, dozens of men and women rushed in, some holding framed photos of their deceased relatives.

As the women cried and pounded the ground, some shouted the names of their deceased sons, the men sobbed in scarves folded over their faces.

Kahsu Gebrehiwot, a priest at the Dengolat Orthodox Church, lamented the fact that even Ethiopian Orthodox leaders did not denounce the killings, let alone the federal government.

“When people die and they don’t say anything, it’s a sign that they fear for their lives,” Kahsu said, referring to church leaders.

“But as the Bible tells us, if you see something bad happening to people, you have to pray, but you have to speak also.”

Source link