[ad_1]

Coronaviruses are RNA viruses that infect both animals and humans. The current 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), has claimed more than 4 million lives worldwide.

This virus has been described as a zoonotic virus and could have originated from bats with an unknown intermediate host. Scientists have suggested a few potential intermediate hosts, such as pangolins, rodents, and bats. However, the transmission dynamics associated with the jump of the virus between different species, including humans, is unclear.

Determination of large species that can be infected with SARS-CoV-2

Several studies have been carried out to identify the wide range of species that can be infected with SARS-CoV-2. Researchers determined the affinity of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) from different animal species for the SARS-CoV-2 (S) spike protein. Previous research has shown that susceptibility to infection varies from species to species. A higher susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 has been found, in cats and members of the Felidae family, due to the virus’s strong affinity for the ACE2 ortholog. However, dogs are found to be less susceptible to the virus due to the lower expression of ACE2 in airway cells.

Previous studies have reported that different viruses from the Coronaviridae family can infect both domestic and wild cats. These viruses are classified as feline coronaviruses (FCoV). These studies have shown that felines infected with the coronavirus can develop mild enteric disease (feline enteric coronaviruses; FeCV) or that the viruses can mutate and create the feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV). FIPV is more contagious and can cause serious illness that can lead to death.

Importance of studying the clinical signs of SARS-CoV-2 infections in felines

Typically, pet cats share a close relationship with their owners. In addition, the felines in the zoo or the wildlife center are very close to their keeper. Therefore, an increasing number of reports of feline SARS-CoV-2 infection has created the need to understand the clinical implications of SARS-CoV-2 infections in felines.

Now a new systematic review has been published in the journal Animals which focuses on clinical symptoms in felines diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 around the world.

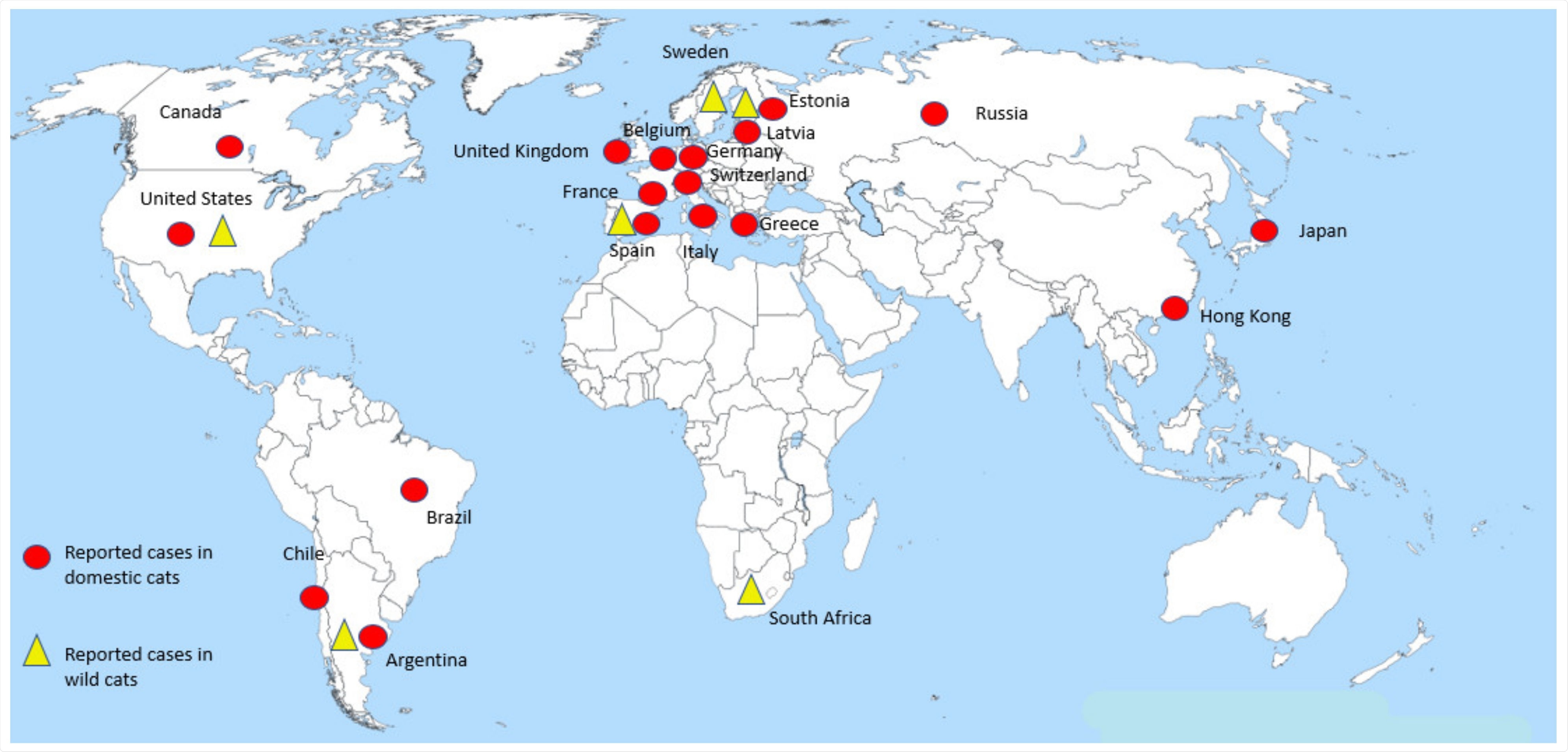

Distribution of reported SARS-CoV-2 cases in domestic and feral cats worldwide. Red circles indicate cases in domestic cats reported by country. The virus has been detected in at least three different continents (the Americas, Europe and Asia) in these animals. Yellow triangles indicate cases in captive wild cats that have been reported in the Americas, Europe and Africa.

Scientists performing this review implemented different search strategies to obtain searches associated with felids diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infections from existing databases and found 19 articles and 65 detailed reports from official sources. .

The main official source of information was the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) website. Here, the authors found evidence of 76 domestic cats in the United States with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, only 22 documented relevant information regarding the appearance or absence of clinical signs among these cases.

A worldwide distribution pattern has been observed in felids infected with SARS-CoV-2. However, most of the cases have been reported in the Americas and Europe. Such an observation corresponds to the fact that these regions have been massively affected by the COVID-19 infection. Limited studies are available on infection of felids in other severely affected regions, such as India and Brazil.

Clinical symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection in felines

Both domestic and wild cats have been reported to be infected with SARS-CoV-2. The following section describes the clinical symptoms associated with the disease.

Domestic cats

In 54% of the cases, the cats were asymptomatic. They were identified because their owners were diagnosed with COVID-19. So the researchers, out of curiosity, screened the cats for the disease and interestingly discovered that they were positive for COVID-19.

In the remaining 46% of cases, cats exhibited clinical symptoms associated with COVID-19 infection. Of these infected felines, 26 survived and six died from the infection.

One of the reports indicated that the cats developed shortness of breath and tachypnea. They were also diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and Mycoplasma haemofelis infection.

One of the cats who died from the disease had clinical symptoms such as a runny nose and neurological signs such as pressure on the head. Autopsy symptoms indicated that the cat developed bacterial meningoencephalitis.

Cats infected with COVID-19 have also been diagnosed with anemia, thrombocytopenia, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Ultrasound examination showed a broncho-interstitial pattern in the lung.

In addition, tissue analysis revealed signs of severe pulmonary edema, hemorrhage and congestion in the infected cats. Some of the other symptoms, such as vomiting, mouth ulcers, and diarrhea, have also been reported.

Wild cats

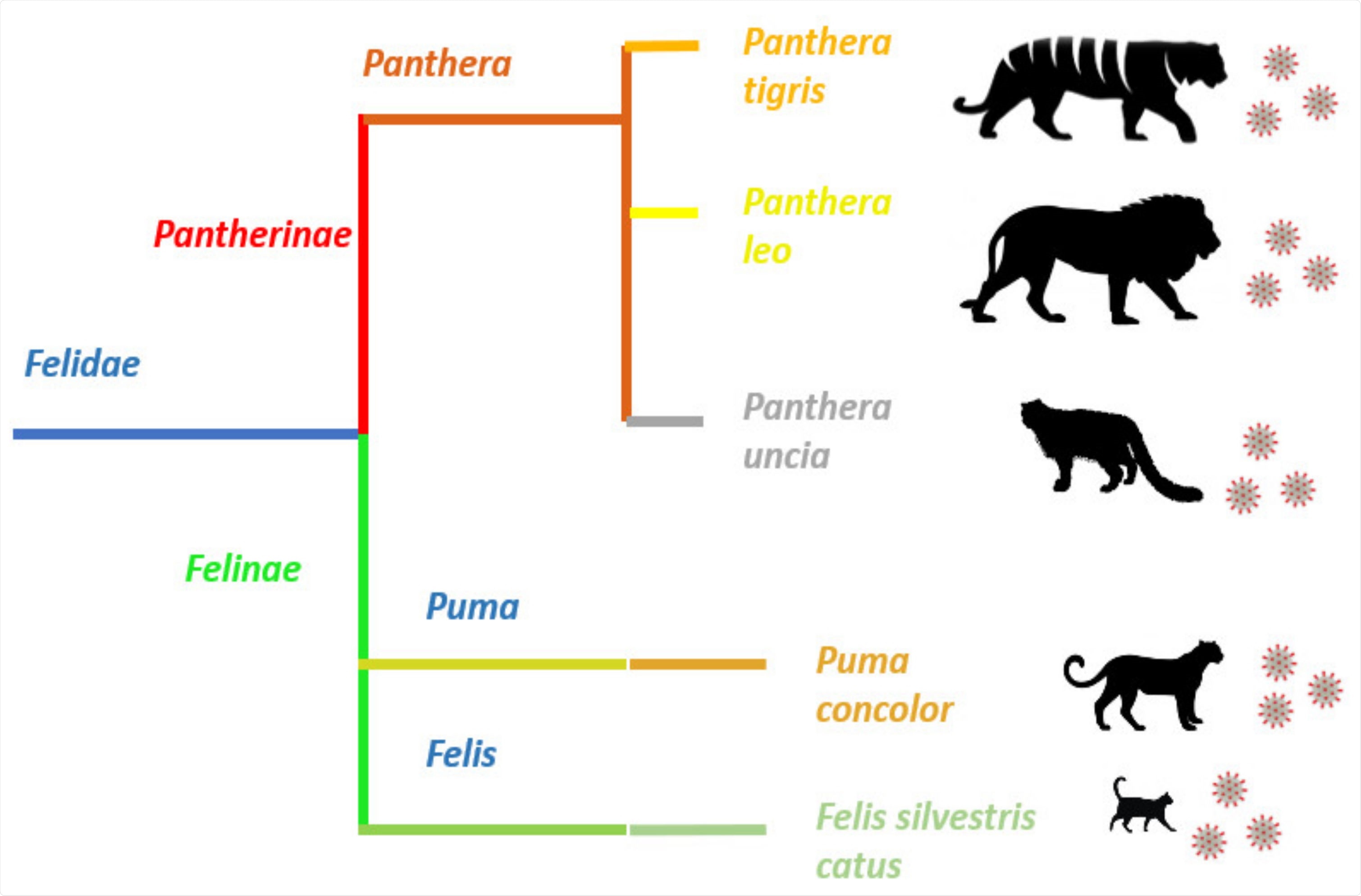

Several cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in wild cats have been reported worldwide. Scientists have revealed that members of the genus Panthera (e.g. tigers, lions, and snow leopards) and the genus Puma (e.g., Puma concolor) have been infected with the virus.

Infection of wild cats with SARS-CoV-2 is associated with human-animal transmission, where staff responsible for caring for these animals tested positive for COVID-19 and could have transmitted the disease to animals.

All animals that tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (except one asymptomatic tiger) showed clinical signs such as coughing and wheezing. In addition to respiratory symptoms, other symptoms such as lack of appetite and lethargy have also been reported.

Felidae species reported with SARS-CoV-2 infection. SARS-CoV-2 infection has been reported in members of two subfamilies, Pantherinae and Felinae, belonging to the Felidae family. Despite the obvious morphological differences between pantherids and felines, the virus is able to infect members of these two dissimilar families and cause very similar clinical signs.

Conclusion

Experimental studies have shown that cats previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 can be re-infected with the virus. However, infected cats could not pass the infection on to another healthy cat.

Histopathological studies have shown that infection with SARS-CoV-2 can cause damage to the nasal and tracheal mucosa and lung parenchyma. This may be because virus replication occurs in these tissues. Histopathological lesions showed suppurative lymphoplasmacytic rhinitis of the nasal turbinates and lymphoplasmacytic tracheitis and alveolar histiocytosis.

The authors conclude: “Given the current complex situation resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of viruses with zoonotic potential, it is of paramount importance to establish national and international surveillance systems to monitor up close the development and appearance of SARS-CoV-2 and other agents of public health importance in animals and its possible “spillover” into humans and its possible “spillover” – causing problems with public health – stressing that all efforts should be focused on the concept and implementation of “One Health / One Medicine” to understand how aspects involving the environment, animals and humans could substantially contribute to control epidemics in the near future.

Source link