[ad_1]

Joshua Burke is a policy fellow and Rebecca Byrnes is a policy badyst, both at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

The UK government has set itself an unprecedented challenge in legislating to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, the first major economy to do so. It now faces the task of actually reaching that goal.

Yet the UK is also in the process of leaving the European Union, putting the country's main carbon pricing mechanism at risk. The EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), which is starting to drive significant CO2 emissions.

This adds pressure on the UK to reconsider its options for carbon pricing, given the important role it can have in giving incentives to move away from polluting business models.

As the UK plays a leading role in the market, it is important to draw from the experiences of other economies. We set out to do just that in research published today, which we have summarized in the article, below.

Pricing schemes

As the UK leaves the EU it has several options for replacing its membership of the EU. It could potentially negotiate to remain apart from the scheme; it could create a new ETS, which is either linked to the EU ETS or which operates only within the UK; it could implement a new carbon tax.

While the government has a carbon tax of 16 cents per tonne of CO2 in the box of a no-deal Brexit – roughly half of the EU ETS price – it has yet to decide on its longer-term approach. This question is the subject of an ongoing consultation and the reason for our new research.

There are currently 56 carbon pricing schemes in operation worldwide that can offer the UK chooses its preferred option. These 56 schemes are split between 28 and 28 based on carbon trading and 28 national and subnational jurisdictions using a carbon tax. The 28 tax schemes cover just 5.6% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

This number might seem small, but the adoption of carbon pricing is on the rise. No fewer than five new tax regimes on January 2018 and July 2019, and further initiatives are planned.

Three dimensions

Our research finds that carbon taxation schemes vary greatly, particularly along three dimensions: the level of the tax, the share of emissions covered, and the use of tax revenues.

The variation between the high and low end of these dimensions can be extreme. Poland has a carbon price of just 0.06 (PLN 0.3) per ton of CO2 (tCO2) covering all fossil fuels, while Sweden's tax is set at £ 100.30 (Kr 1,180) per tonne. This applies to CO2 emissions from the transport and buildings sectors.

The overall average across all jurisdictions is £ 18.07 / tCO2. In the UK, we have recently found that we are in the United Kingdom with more than 40% of our net sales.

On the share of emissions covered, there are also big differences according to the type of carbon tax, among the taxes currently in force.

For example, in Sweden, the share of the covered market is 40%, including those covered by the EU ETS. In the Canadian province of British Columbia – which is not participating in the EU ETS – it is 70%, being applied uniformly to all fossil fuels within its borders. The only major exemptions are inter-jurisdictional shipping and flights (Journeys Between BC and the Rest of Canada).

In the UK, the Carbon Price Support (CPS) – an upstream tax paid by fossil fuel power stations – covers 23% of emissions. In addition, a wider swathe of the UK industry faces a separate share of the Climate Change Levy (CCL). In total, our calculations suggest that 35% of UK greenhouse gas emissions are covered by one of the various carbon pricing schemes.

There are also significant differences in the way governments use revenue from carbon pricing. The UK's Carbon Price Support is the least prescriptive, with all of them as general income tax. This allows the exchequer to decide how to spend it.

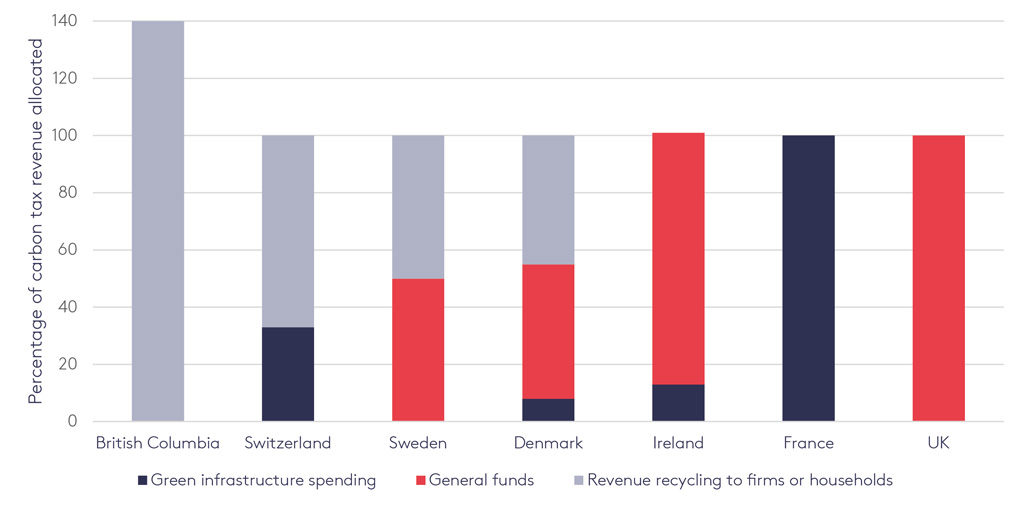

Raising money in the money (red flags on the chart, below), most other schemes include rules on earmarking (or "hypothecation") or revenue recycling (blue bars) .

Allocations of income from seven examples of carbon taxes between general funds (red), green spending (gray) and rebates for households and firms (blue). Source: Burke et al. (2019) using data from Carl and Fedor (2016)

Interestingly, British Columbia's carbon tax makes it easier than ever, as the chart above shows. In 2015, 120% of carbon tax revenues were given to firms and households. This grew to 140% in 2018, achieved by decreasing income taxes beyond what would be needed to achieve revenue neutrality.

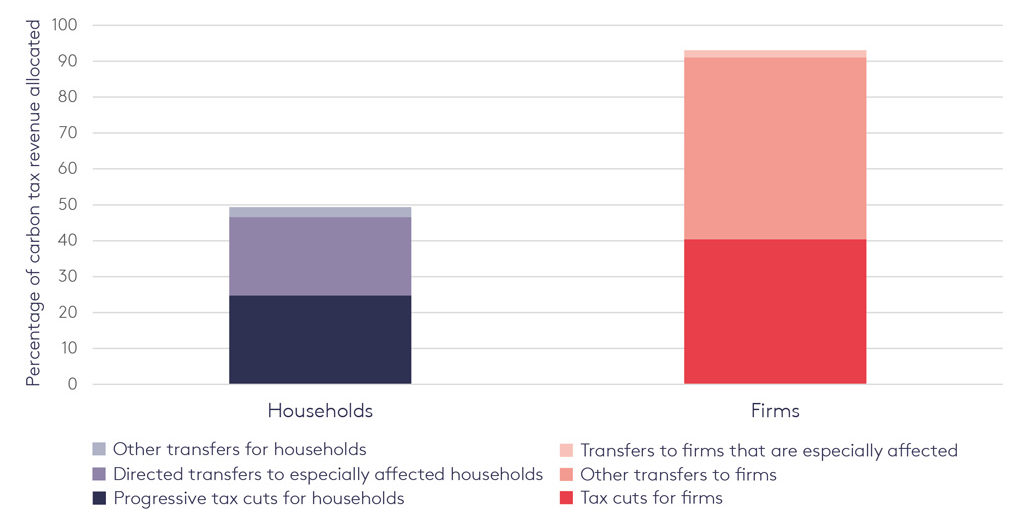

This revenue is divided between general tax cuts for households (dark blue in the chart, below) and firms (dark red) versus directed or more general transfers (lighter shades).

Allocation of British Columbia carbon tax revenue between households (shades of blue) and firms (shades of red and pink). Source: Burke et al. (2019) using data from British Columbia Budget and Fiscal Plan 2018/19

Lessons from abroad

Our research founds these examples from around the world provide three important lessons for the design of a possible new carbon tax for the UK.

First, taxing carbon can present significant political challenges, both before and after implementation. Second, the design and communication of the scheme can improve public acceptability. Third, ounce in place, carbon taxes do bring down emissions – as explained below.

Taxing carbon tends to be more difficult politically than other climate policies such as subsidies and regulation. In some countries, "escalators" have often been introduced, or other schemes have survived – as happened in Australia, for example – because of political difficulty.

Most obviously, challenges around the political feasibility of a carbon tax have been visible in the backlash in France by the "yellow vests" movement against the "Climate Energy Contribution". It is worth noting, though, that this is the importance of scheme design – with some of the opposition fired by the fact that it is followed by tax cuts for high-income households.

There are several reasons for public resistance to carbon taxes, explored in a recent piece published by Nature. Often, the article suggests, people suspect that the government's main motivation is to raise revenue rather than reducing emissions. Therefore, they consider their personal burden too high, even if they agree with the environmental objective. More broadly, people feel that carbon taxes fall disproportionately on low-income households.

However, public acceptance can be increased through smart design and clear communication. British Columbia is a good example of an innovative tax design that achieves public acceptance.

Progressive outcomes

One way to achieve a progressive outcome is by recycling carbon tax in the form of a "citizen dividend".

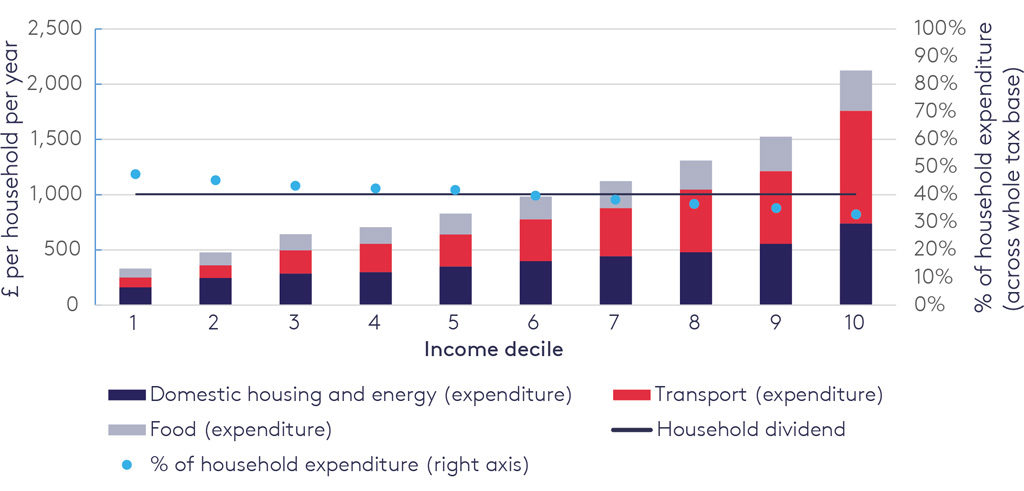

The chart below illustrates how the UK could be said to be recycling a £ 40 / tCO2 tax into a uniform lump-sum dividend of around £ 1,000 per year to each household (the black line). This payment could be greater than that of the other countries, leaving those with the higher incomes paying more tax-rate (right hand side).

Illustrative tax payment and income (£) by income decile. Source: Burke et al. (2019) using data from Gough et al. (2012).

(In the chart above, household greenhouse gas emissions for household income include both direct emissions, such as gas consumption for heating, and and not all indirect emissions may be taxed.

The hypothetical UK carbon tax illustrated in the chart would affect the income of households (income decile 1), but only 33% of household expenditure for the richest 10% (income decile 10). (These percentages are illustrated by the dots on the chart.) However, the dividend of £ 1,000 per year, the lowest income income – half of all households – better off overall.

Looking at political acceptability in the process of designing a carbon tax could help governments such as the United States.

Cutting emissions

Long-established schemes in the Nordic countries, which have received less opposition, show that they have been successful in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. However, the emissions cuts are not necessary as they would be required under a net-zero trajectory. In part, this has to do with relatively low tax levels and widespread tax exemptions.

In the UK, carbon taxation through the Carbon Price Support has been linked to the fall in coal generation by 73% between 2013 and 2017.

How much weight is given to each of these lessons depends on the political context. If the greatest obstacle to carbon pricing is building a broad coalition of citizens, then the evidence shows that it can be overcome by using direct transfers in the form of a dividend.

Where can I get the best price, compensating firms through tax rebates may be preferable.

As the UK prepares to leave the ETS, it has an opportunity to draw lessons from the best examples of carbon pricing from around the world as it strives to achieve net-zero. Whichever approach is important, a price on CO2 is likely to play an important role in reaching its target.

Sharelines from this story

[ad_2]

Source link