[ad_1]

A new Australian study, published overnight in Nature Communications, provides insight into how children’s immune systems respond to infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

This is the first study, to my knowledge, that directly compares children and adults with mild COVID.

Children are less likely to be infected, and when they are, they are more likely to be asymptomatic. This contrasts with other viral and respiratory infections that are more common in young people.

This new research helps explain how children’s immune systems work when confronted with coronavirus – and gives us clues as to why they generally seem to fare better than adults.

Read more: Worried your child might contract coronavirus? Here’s what you need to know

Children (the immune system) are fine

Researchers studied 48 children, mostly in primary school, in 28 households during Melbourne’s second wave. All children have been exposed to the coronavirus in their homes by infected parents.

This study focused on the “innate” immune response in children, which is the first part of the immune system’s attack against a virus (or bacteria, or other pathogens). The innate immune system plays an important role in viral protection before the body produces antibodies.

The study found that there were dynamic changes in the early immune responses of children, compared to adults infected with the coronavirus.

Learn more: Explainer: what is the immune system?

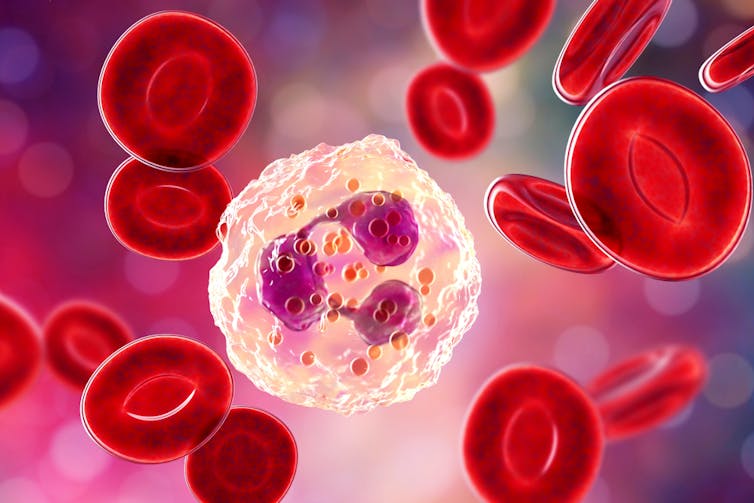

A key innate immune cell that was elevated in children exposed to the virus was a type of white blood cell called “neutrophils”. These cells patrol the body for infections. When they discover a pathogen, they have a unique ability to respond by trapping and killing the invading pathogen (in this case, the coronavirus).

This role can ensure that the virus cannot infect more cells. This potentially lowers the “viral load”, essentially the amount of virus in your body.

on www.shutterstock.com

For some of the children in the study, the early immune responses kept the viral load so low that they never returned a positive test, although they were tested throughout the study and they have been exposed to the coronavirus.

One of the strengths of this study is that it was “longitudinal”, that is, it looked at families over time, rather than just at one point in time. Researchers looked at families’ immune responses right after exposure to the virus and returned more than 30 days later to see what had changed. This enabled them to identify the main changes induced by exposure to the virus.

Children vs adults

A key question emerging from this research is: why did children show such strong immune responses, resulting in few or no symptoms, when their parents were very sick?

It’s a difficult question to answer, at least so far. But the main differences in responses probably lie in the early responses of the immune system.

Some previous research might give clues.

One theory surrounds the fact that children have fewer receptors called “ACE2” in their airways. These receptors are the entry route for the virus into our cells. In theory, fewer ACE2 receptors mean less of a chance for the virus to enter and infect our cells. The virus does not survive very long outside of a cell. With fewer ACE2 receptors, it can give innate immune cells more time to control the virus as much as they can while waiting for other immune cells to come in and help.

Read more: ACE2: the molecule that helps the coronavirus to invade your cells

Another possibility is ‘interferons’, which are warning signals emitted by cells to tell the body that there is a virus around. Researchers believe that higher levels of interferons during the early phase of an infection are very important in controlling the coronavirus. Potentially, interferons may help promote the increase in neutrophils seen in children, compared to the lower numbers seen in adults.

The wide range of symptoms of COVID are both intriguing and frustrating. The conventional wisdom was that children are more susceptible to respiratory illnesses than adults – ask any parent! But with COVID, it seems to be the opposite.

Often times when we think we have defined a specific mechanism for how this new virus works and how our body responds to it, it turns out that such a mechanism is different in different people. We can see this in the wide range of symptoms that different people have – some have a runny nose, others have a cough, and others suffer from extreme exhaustion and respiratory distress or develop a ‘long COVID’, in which symptoms persist for months.

The coronavirus is still keeping immunologists on their toes. Studies like this help solve part of the puzzle of understanding who is most at risk for serious illness and why.

Read more: Five Life Lessons From Your Immune System

Source link