[ad_1]

Photo: Robert Fairer / Robert Fairer

The Fendi showroom in Milan spans an old industrial building on Via Solari which also includes a track large enough to accommodate around 20 Roman-sized columns. The columns remind us that the Fendis come from Rome. But when I arrived at Via Solari on Tuesday afternoon – the day before the show and the start of the Milanese spring 2022 collections – it was a whole different family that I met in the showroom. At one end, chatting to each other as the models came and went for fittings, were Amanda Harlech, who was Karl Lagerfeld’s longtime muse at Chanel and Fendi; London artistic director Ronnie Newhouse; and well-known stylist Melanie Ward. Sitting nearby, conversing, were Silvia Venturini Fendi and director Luca Guadagnino. And in the midst of it all, instructing the models on their movements, was choreographer Les Child, who worked with the late dancer and choreographer Michael Clark, who worked with Alexander McQueen and John Galliano.

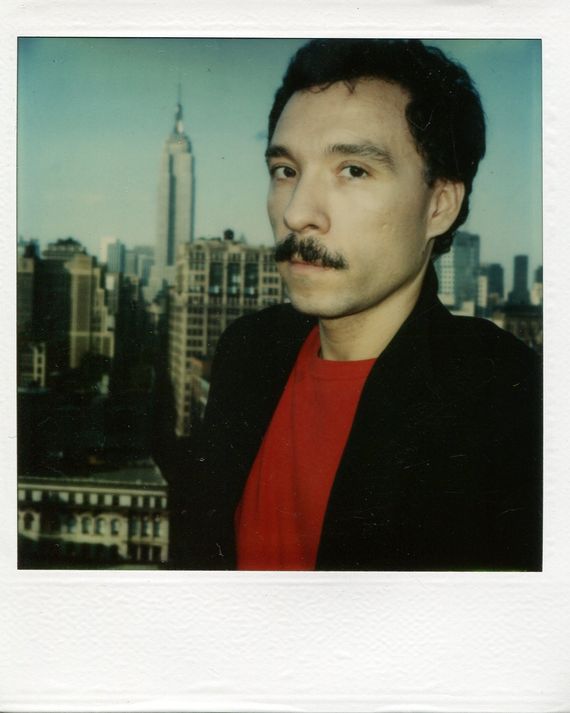

Kim Jones, the group’s catalyst and the brand’s creative director, was in the middle of the room, chatting with Paul Caranicas and his niece, Devon Caranicas. They manage the archives of legendary illustrator Antonio Lopez and his creative partner Juan Ramos. Late last year, Jones asked the Caranicases if he could use some of Lopez’s designs for Fendi. The results will be displayed on the track, amidst the columns of disco lighting, on Wednesday.

Antonio Lopez on the roof of his 31 Union Square West Studio, New York City. vs. 1978

Photo: The estate and archives of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos

The timing of a Lopez-inspired collection is more than a little symbolic. First of all, Lopez himself was famous for bringing together a sort of fashion and art family, made up of models like Donna Jordan, Jerry Hall, and Jessica Lange, who went from modeling to acting, as well as ‘a new group of stylish Latino boys from the Bronx, where Lopez grew up after his parents moved from Puerto Rico. As writer Alicia Drake pointed out in The beautiful fall, her book from the 1970s and 1980s, Lopez was one of the first to show that blacks, brunettes, gays, trans and the working class could be glamorous. In his illustrations, and later his photographs, he captured the energy and sexuality of the era – on the dance floor and in the streets. It also had a huge impact on Lagerfeld, whom he met in Paris around 1969, when Lagerfeld was at Chloe’s. Although Lopez and Ramos did not work for him in an official capacity, it is generally believed that the two brought ideas and also released him during their six years in Paris. You can see the effect in photos of Lagerfeld in his favorite Parisian haunts or in Saint-Tropez. It’s Karl without glasses or ponytail.

This season marks the return of live shows to Europe on a large scale, although everyone will be masked and spaced out. For Jones, this show will be especially important. A widely admired menswear designer who is the creative director of Dior Homme, Jones made his womenswear debut at Fendi weeks before much of Europe was blocked by COVID-19. Her subsequent collections, including haute couture, were presented digitally, and some critics, including myself, felt her feminine forms, while elegant, were as imposing as Roman marble. Anyway, he needed to relax.

The estate and archives of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos.

The estate and archives of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos.

Lopez certainly helped in this process. “I realize I’m learning on the job,” Jones told me last week when we spoke by phone, adding, “It’s not about me, it’s about the house. that’s how I think. And Antonio has a hand in the house, and it’s a hand that I admire, so I wanted to talk about it.

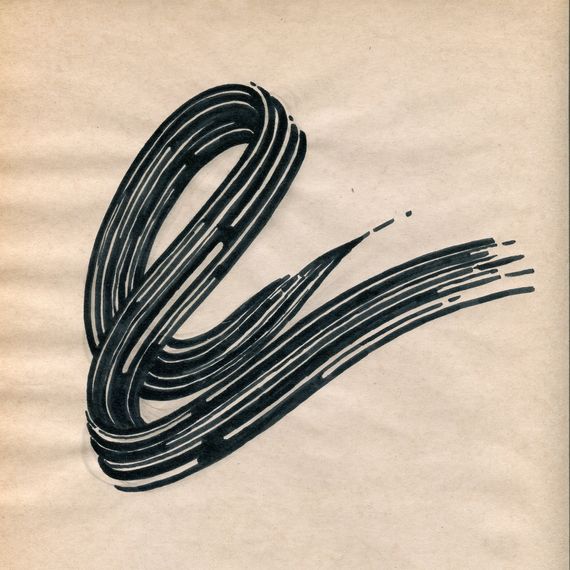

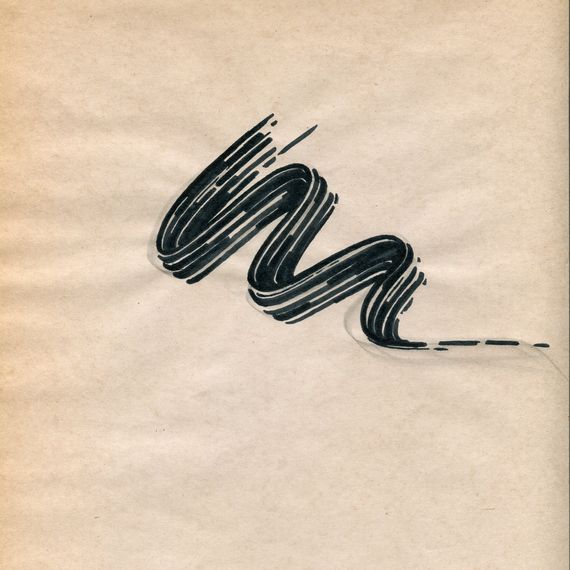

Along with her “right hand” of many years, Lucy Beeden, Fendi’s Design Director, Jones toured the Antonio Archives in Jersey City. The Caranicases estimate that as many as 600 works, ranging from fashion illustrations and packaging designs to stylized brushstrokes, have been shared with Jones and Beeden.

Brush Studies, c. 1978 The estate and archives of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos.

Brush Studies, c. 1978 The estate and archives of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos.

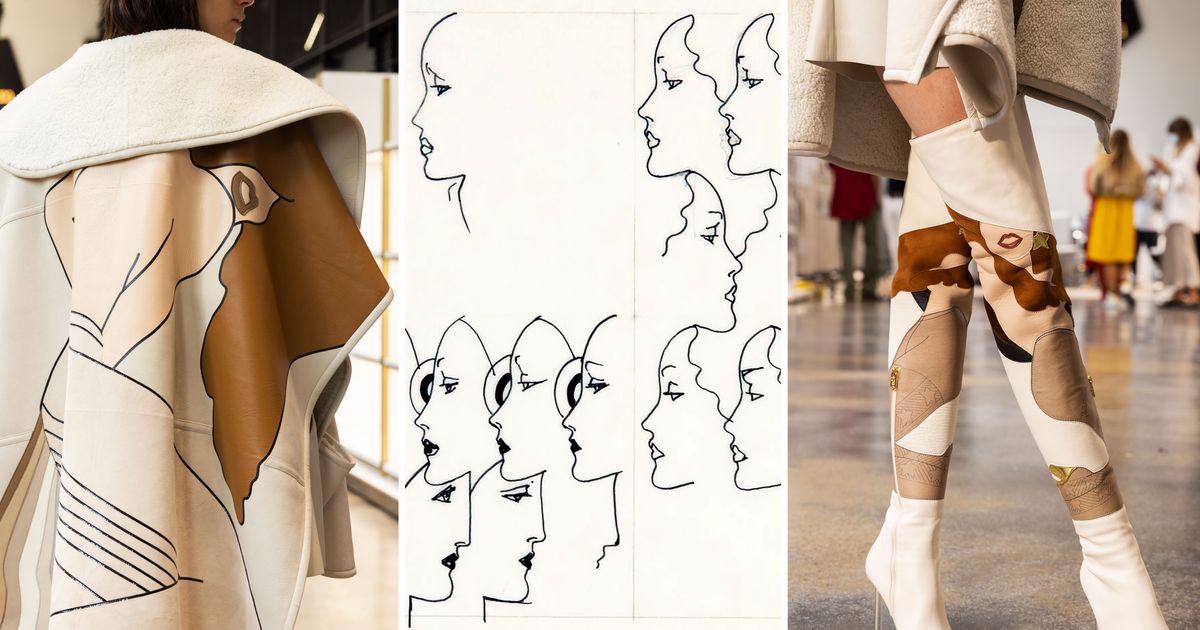

What amazes me is how much the collection has evolved since Jones first showed me pictures in June. Lopez’s hand was clearly evident in the short silk dresses, handbags and boots that featured Lopez’s exaggerated and richly colored female designs. Yet last week when Jones shared new images and when I saw the clothes in the Via Solari showroom, Lopez had become a more invisible presence.

It was because Jones had refined and refined his ideas. If this collection is about anything, it’s about how to exert a powerful influence and direct it to your own vision. Other designers have used Lopez’s work – notably Carol Lim and Humberto Leon for a 2017 Kenzo collection – but this often involves reproducing an image on a dress or t-shirt. (Of course, designer-artist collaborations are not new. In 1966, Yves Saint Laurent produced a series of dresses, depicting figures and heads of women, based on Pop Art by Tom Wesselmann.)

“What’s so exciting about Fendi is that they haven’t so literally translated the artwork,” Devon Caranicas said last week on a Zoom call.

“They reinvented it,” added Paul.

From left to right : Photo: Robert Fairer / Courtesy of FendiPhoto: The estate and archives of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos

From above: Photo: Robert Fairer / Courtesy of FendiPhoto: The estate and archives of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos

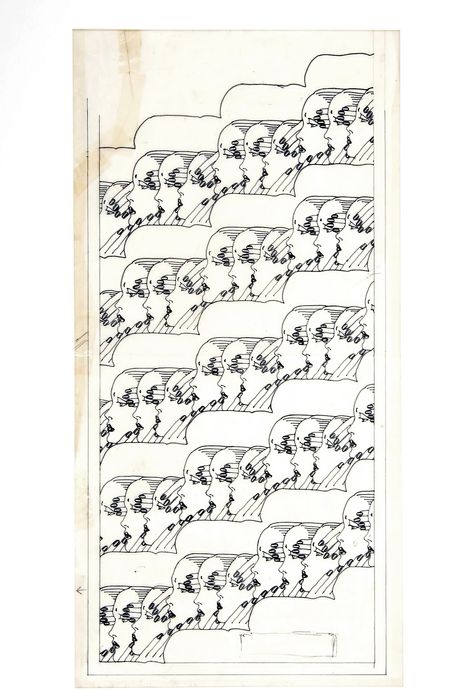

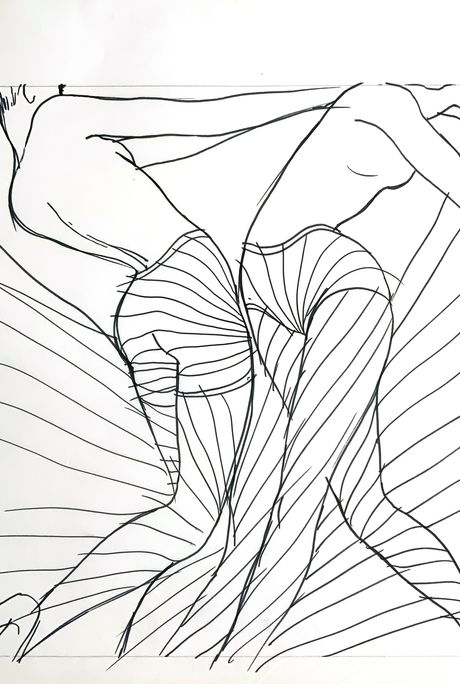

Indeed, Jones brought three-dimensional life to the artwork, especially black brushstrokes that appear over a flowing white kaftan as well as a white mini dress. (The original illustration was roughly the size of a person’s hand.) A series of alternate line drawings of a woman’s head in profile – which Lopez originally made for a packaging project – became a repeated zigzag stripe in gray, red and white for a belted coat. There were also gorgeous pieces in a silk jacquard stripe, with a Fendi logo – apparently designed by Lopez – suddenly incorporated into the design. Back in the mid 60s for The New York Times Magazine, Lopez did a series of fashion illustrations with bold stripes. What’s great about the collection is that you have to be a Lopez fan to recognize the source. It is not that obvious.

From left to right : Photo: Robert Fairer / Robert FairerPhoto: The estate and archives of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos

From above: Photo: Robert Fairer / Robert FairerPhoto: The estate and archives of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos

“It gives it youth,” Jones says of the artwork.

But Jones is perhaps modest on his own hand in this collection and, too, Fendi’s transformation of the Lagerfeld decades. In the ’80s and’ 90s, a Fendi show was really about fur – and Lagerfeld was doing revolutionary things, like shaving mink and getting rid of liners. But, as Silvia Fendi reminded me yesterday, ready-to-wear at Fendi was something that hardly existed. It was fur and bags.

Jones, on the other hand, brought tailoring to Fendi from his years as a men’s designer. And this new collection brings a playful side. “It’s bold for Kim,” Fendi said. “It’s something very different for him. She also pointed out that Jones is not ransacking the Fendi archives for his ideas. Instead, she said, “he thinks about the world around Fendi and Karl.”

Hence the link with Lopez. Of course, as many people know – and as a recent documentary made clear – Lagerfeld ultimately ditched Lopez and Ramos as friends, and he didn’t answer Lopez’s call for the job when the artist died of AIDS in 1987. So you cannot marvel at the curious synchronism of things, of a Fendi show now based on Lopez’s work.

The estate and archives of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos.

The estate and archives of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos.

Silvia Fendi speculates that Lagerfeld let people down because he wanted his complete freedom. “The moment he felt too attached to someone,” she said, “he would let it go.” Jones wondered if he refused to help Lopez in the end because he was afraid of death himself.

Jones paused. “It’s funny. I’m quite like Karl in the way I work but I don’t let people down. My inner circle is very close and always has been.

Paul Caranicas, who lived with Lopez and Ramos in Paris in the 1970s and knew Lagerfeld at the time, naturally has his own take on the matter.

“Things come full circle and there’s not really an explanation as to why these things are happening,” he said. “Kim is obviously a very talented person and recognizes Antonio’s genius. I think Karl was a little jealous of Antonio’s genius, and maybe that way it’s poetic justice that things come full circle. loop.

Source link