[ad_1]

Sam Droege really loves bees. He thinks they are cute, on the one hand. (Just look at this little probe, these moving antennas, and those compound eyes, wider and more open than those of a doe.) He can not get enough of it, and sometimes his enthusiasm wins. "I would say, like many other apologists," he says, "that most bees are probably nicer than most kids."

It's hard to tell if he's joking. But Droege's work at the United States Geological Survey (USGS) is both scientific and public. His clients are bees and his mission is to persuade humans to love them as much as he does.

Droege is a wildlife biologist at Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Maryland, where he is developing a program to inventory and monitor North American anthophils. Some of his tasks involve field work, which he appreciates so much that he describes his trip as a "vacation" to analyze the bee fauna of Kruger National Park, South Africa. "I can not think of anything that feeds my mind anymore." says, "that to make an uninterrupted natural history in one part of the world warm, sunny and filled with bees, while others endure the snow in the north". Even if you're never going to walk with him, Droege will do everything possible to convince you that bees that stop over the flowers of the dry landscape are worth as much the fainting as the pride of the past of the lions.

For this, he turns to Flickr, where he mastered the subtle art of hype. Droege shared thousands of photos from the USGS 'inventory and surveillance laboratory of bees, mostly portraits of specimens resting on black ink grounds. The insects' characteristics are thus easy to observe and document, but they also look harsh, evoking glamorous portraits of brutal rock stars or a still life of luxury handbags in a glossy magazine. Each photo is accompanied by writings of information on the appearance and habits of the subject, as well as, often, some bucolic verses of Emily Dickinson and an emoji of the old school looking a little like the head of a bee. Nearly 800 of Droege's favorite photos are collected in an album he calls "Eye Candy".

Even when the images and legends are playful, they are all at the service of science – or describe its limits. Take the case of a small male bee of the genus Mourectotelles. "What an attractive bee," writes Droege in the legend. "Unfortunately, it is almost all we can say about this species, except that it is found in the western temperate regions of South America" (this individual is native to # 39; Argentina). As the insect has not yet been classified in a specific species, Droege has dubbed it "The pretty hairy face of the bee". This name, along with other idiots of this kind, are internal spaces reserved for Droege and his colleagues, but sometimes used to indicate the essence of the species we represent, "he says. "It's mainly an accident that anyone is bumping into our hidden nomenclature."

If someone falls in love with these charms, this could pay off. As might be expected, research has shown that the more friendly a species seems, the more enthusiastic people are in the idea of keeping it. Overall, people seem to be feeling pretty good with bees, according to a 2017 study in PLOS One. For this work, German researchers interviewed 499 students and 153 beekeepers. They found that novices and amateurs were on board with protective bees, but that does not necessarily mean they know a lot about them. In another study conducted in 2017, ecologists from Utah State University found that even people who wanted to preserve bee habitats, limit the use of pesticides and protect the settlements against the collapse were finally a little afraid of insects. "In our recent survey, 99% of those surveyed said that bees were essential or important, but only 14% could guess the actual number of bee species in the United States out of 1,000," said senior author, Joseph Wilson, of the state of Utah. biologist, in a press release. "Most people have estimated about 50 species of bees, while the exact number is about 4,000 known species."

This bee of the genus Lipotriches was collected in Australia. USGS Beekeeping Inventory and Surveillance Laboratory / Public Domain

This bee of the genus Lipotriches was collected in Australia. USGS Beekeeping Inventory and Surveillance Laboratory / Public DomainThe glamorous shots "touched an audience that would never read any of my papers," says Droege. The photos show the dazzling diversity of bees – tiny, fuzzy, wide, long-nosed, emerald, eggplant. The photos flew over the Internet, even going as far as landing on the subreddit r / woahdude, a house for images and sound that "makes a sober person feel stoned or that that- This trip is stronger. , legends remind us that bees and other familiar pollinators are just the tip of the iceberg of biodiversity.

Laurence Packer, a melittologist (that is, a bee expert) from York University in Toronto, who collected this "Bee cute furry face" specimen, notes that experts are also struggling to keep them straight. When he gives identification tests to students and professors, he often sees that even people who have been working in the field for years are fooled by other insects that look like bees and bees that look like other insects. "There are 20,355 species of bees described and no one on the planet can recognize them all, for pretty obvious reasons," said Packer. There are too many for one brain to remember – and they will surely be joined by more bees that will be documented in the future.

Laurence Packer found this long language Geodiscelis longiceps in the Atacama desert in Chile. USGS Beekeeping Inventory and Surveillance Laboratory / Public Domain

Laurence Packer found this long language Geodiscelis longiceps in the Atacama desert in Chile. USGS Beekeeping Inventory and Surveillance Laboratory / Public DomainPacker travels the world collecting cash and making frequent trips to Argentina and Chile. (Droege occasionally follows.) Sometimes a region will be far enough apart that Packer is confident enough that almost all the species he finds will not be listed in the scientific literature. He collected some while descending a mountain in the Atacama desert, for example, in what he called a "spectacularly strange" scenery, where a few bouquets of flowers gave way to a sea of sand and a tuft of pale bees have swarmed. Sometimes he does not know if anything has been recorded before comparing the specimen with the identification keys or performing a DNA analysis. The Packer laboratory has already found about 200 species and 150 more manuscripts are in preparation.

There is still a lot of academic work to do: Packer suspects that several thousand species still need to be collected and described. "Justin[[[[Mourectotelles]only dozens of graduate degrees exist, in the expectation that someone is exploring the life story of this group, "writes Droege on Flickr. Public relations campaigns like Droege's could spark curiosity and inspire the will to help them where they are struggling. "If you do not know something," says Packer, "you can not love him."

"Bees do not have a voice," says Droege. "I'm happy to speak partially for them."

Melitta hemorrhoidalis is commonly found in Europe. USGS Beekeeping Inventory and Surveillance Laboratory / Public Domain

Melitta hemorrhoidalis is commonly found in Europe. USGS Beekeeping Inventory and Surveillance Laboratory / Public Domain

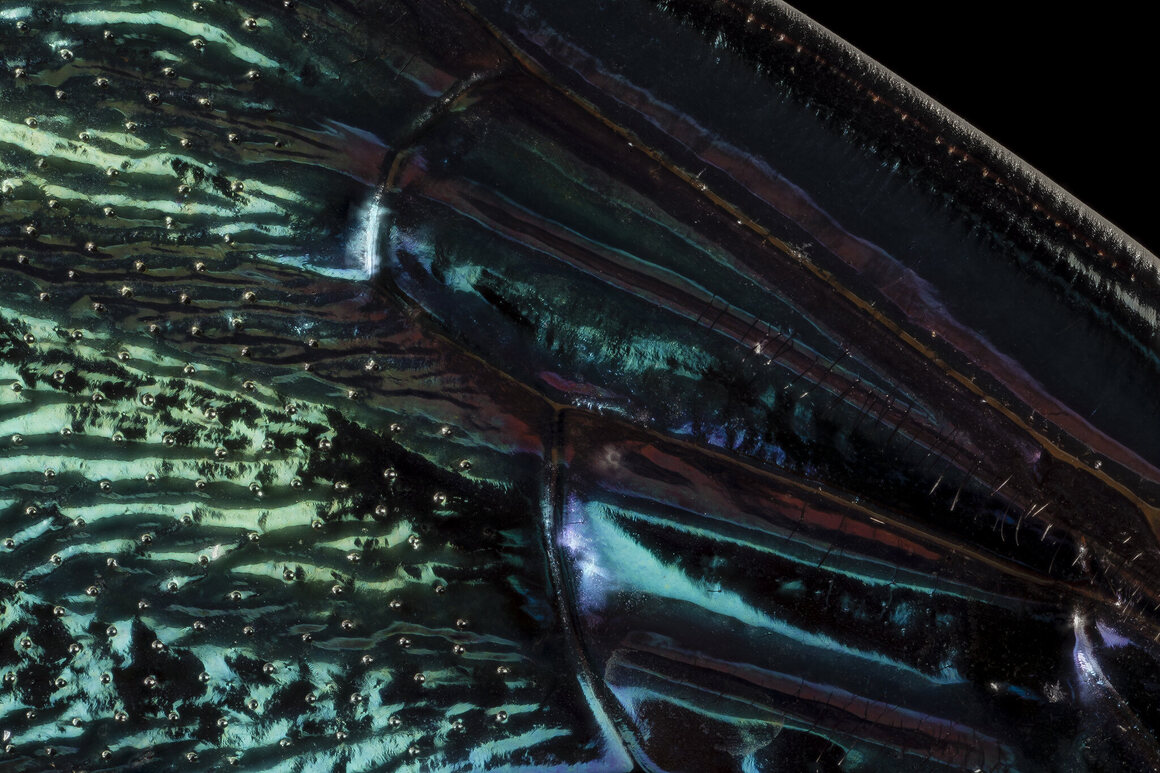

Droege has entered tightly on the abdomen and the wing of this bee of the genus Xylocopa. USGS Beekeeping Inventory and Surveillance Laboratory / Public Domain

Droege has entered tightly on the abdomen and the wing of this bee of the genus Xylocopa. USGS Beekeeping Inventory and Surveillance Laboratory / Public Domain

[ad_2]

Source link