[ad_1]

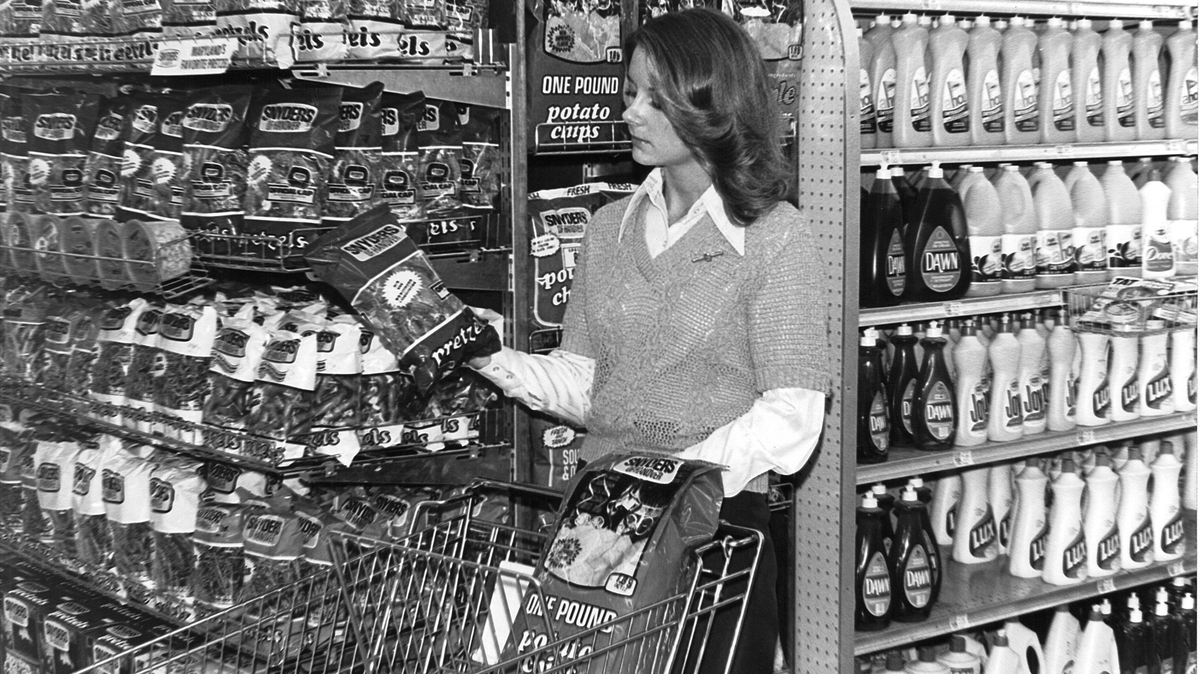

A woman shopping in the 1970s picks up a bag of Snyder pretzels. Today, Hanover remains a center for making snack food, even though the food industry is evolving all around.

Courtesy of Snyder from Hanover

hide legend

activate the legend

Courtesy of Snyder from Hanover

A woman shopping in the 1970s picks up a bag of Snyder pretzels. Today, Hanover remains a center for making snack food, even though the food industry is evolving all around.

Courtesy of Snyder from Hanover

Nestled near the Pennsylvania-Maryland border, Hanover District, Pennsylvania, has a population of 16,000 and is at a great distance from Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

Agricultural center with an industrial core, this rural town was known before the beginning of the twentieth century as the place of the last skirmish before the confrontation of the armies of the Union and Confederation at the Battle of Gettysburg, in the summer of 1863. But a providential combination of heritage and modernization, York County, where Hanover is located, has traded its identity from the Civil War for a more savory image: "World Capital of Fast Food. "

Over the past century, no less than four snack food companies have been established in Hanover, including Utz Quality Foods, which has gained cult status among potato aficionados; and Snyder & # 39; s of Hanover, which in 2016 was the best-selling pretzel brand in the country, generating more than $ 216 million annually. Despite the acquisition of Snyder & # 39; s by the Campbell Soup Company in March 2018, these companies, along with two other companies, Revonah Pretzels and Wege of Hanover Pretzels, are domiciled in Hanover. Several other snack food suppliers, including the York Pretzel Company, Martin Potato Chips, Good Potato Chips, Tom Sturgis Ham and HK Anderson are located elsewhere in York County and in the neighboring county. of Lancaster.

In a food landscape dominated by multinational conglomerates such as Frito-Lay and PepsiCo, the century-old survival of Hanover's fast food companies is quite remarkable. Why has the local snack food industry been so successful while other emerging industries, such as Ohio and Southern California, have not taken off? Two unique factors in southern Pennsylvania: the Pennsylvania Dutch and a strategic location just outside the major metropolises on the east coast.

Dutch influence of Pennsylvania

The Pennsylvania Dutch, descendants of German-speaking European immigrants, are among the most identifiable American-made communities. Established in southern and central Pennsylvania in the 18th century, the Pennsylvania Dutch (including sub-ensembles such as the Amish and Mennonites) have earned a reputation for hardworking, inventive and religious people, says Marvin Muhlhausen, archivist at the Yelland Research Library of the Hanover Historical Society.

According to food historian William Woys Weaver, they also had complex culinary traditions combining Old World traditions and American innovations. Hard pretzels are one of the most recognizable Dutch dishes in Pennsylvania. Hailing from German-speaking Europe in the medieval era, once in Pennsylvania, they became a very popular snack sold in regional markets and fairs – easy to prepare and later easy to produce in large amount.

During the visit of the Utz factory, you will discover a set of products and equipment of the company in the thirties.

Shoshi Parks for NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Shoshi Parks for NPR

During the visit of the Utz factory, you will discover a set of products and equipment of the company in the thirties.

Shoshi Parks for NPR

Although the relationship between the Pennsylvania Dutch and chips was more recent than the pretzel, the community has left its unique mark on the snack bar. The potato chips exploded on the American culinary scene in 1853 thanks to George Crum, a cook from Saratoga Springs, New York, of American and American descent. The popular "Saratoga Chips" quickly spread on the east coast until Pennsylvania, a Dutch country before the turn of the century.

Potato chips – potato varieties like Maris Piper, King Edwards and Rooster – that grow particularly well in York and Lancaster counties, have made snack raw materials readily available. But lard was the real reason that potato chips flourished in southern Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Dutch cuisine is full of pork products: beef, sausages, stuffed sow belly and, of course, lard. Pastries and other lean dishes are, in fact, so common in the Dutch country of Pennsylvania that Dirk Burhans, author of Crunch: A story of the American big crust, refers to him as the "bacon belt".

The potato chips also received the lard treatment. Fries in pork fat, the potatoes became hard and crunchy, with a flavor that vegetable oil could not match. According to Burhans, people have become crazy about bacon fries made by companies like Original Good, King's and Zerbe. Even the largest potato chip company in Hanover, Utz, still produces a brand of bacon fries called "hand-fried fries" from Grandma Utz.

Build an empire of snacks

If the Dutch heritage of Pennsylvania is the reason for the "capital of fast food", Hanover is in itself the how. Unlike the more traditional Amish and Mennonite subspecies that populated nearby Lancaster County, the small farming town of Hanover was populated by resident industrialists from Dutch Pennsylvania, who enthusiastically embraced mechanization and factory production, according to Muhlhausen. At the turn of the twentieth century, despite a population of just over 5,000 inhabitants, the main industrial activities evolved from a constellation of local businesses producing everything from leather to furniture, passing by the bricks. Like Hanover, bakeries and food businesses in the 19th century were developing in the same way. In the 1940s and 1950s, the first companies like Olde Tyme Pretzels (the current Snyder of Hanover) modernized their production.

Snyder's mid-century modernization was well planned, closely mirroring a major innovation in local transportation: the Pennsylvania Turnpike. According to Weaver, until the construction of Turnpike, "almost all small towns in Pennsylvania had their pretzel baker". But once completed, the shipment of food products to metropolitan areas such as Baltimore, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh has become more efficient. Hanover's fast food companies were well positioned to capitalize not only on the low cost of rural labor, but also on the fact that workers outside city centers were less likely to join a union, explains Weaver.

While the American manufacturing industry began to decline in the late twentieth century, innovative strategies and a deep understanding of its loyal consumers in the mid-Atlantic, who remain the main consumers of most snacks in Hanover, have allowed these businesses to flourish. Even Snyder's, who sells his pretzels around the world, is largely motivated by understanding the needs of his consumers, according to Chris Foley, director of marketing at Campbell Foods.

"The expansion of snack food industries coincided with the decline of some of the other manufacturing centers during the latter part of the twentieth century," Muhlhausen said. "The happy effect for Hannover has been maintained and has resulted in an increase in employment for its industrious workforce."

Today, Hanover remains a center for making snack food, even though the food industry is evolving all around. And while some of its companies have been grouped into larger companies, others, including Utz, still belong to families and are operated from the city. "We are making adjustments," says Kevin Bidelspach, owner of Revonah Pretzels. The company has found a niche for making pretzels by hand that can not be duplicated by machines. "This has certainly been a big evolution from the beginning, with people like us, but the handcrafted concept allows us to make a very specialized product.We do not try to have our pretzels everywhere; our footprint is more defined. "

Despite competition from global conglomerates, companies such as Revonah and Utz are "essential components" of Hanover, Muhlhausen said. Indeed, confirms Jane Kindon, who has always lived in Hanover, the companies are so intertwined in the fabric of the city that she and her daughter went to school with two generations of snack food families and one of her sons worked at the Snyder factory. A box of "broken" pretzels bought at low prices at the Wege factory was always at hand when his children were young.

"Because of the personal connection, it's just something we grew up with and … our kids grew up with them," recalls Kindon. "But these are well paying jobs, I think people are happy that they are here."

Shoshi Parks is specialized in writing about travel, history and gastronomy. His work has been published in Smithsonian Magazine, Fodor's Travel, Atlas Obscura, Adventure.com, Munchies, Civil Eats and YES! Magazine. Find more of his work at http://www.shoshiparks.net.

[ad_2]

Source link