[ad_1]

“He was looking up and he could see smoke. The smoke… was just covering the sky,” Young Yu said.

The arson that destroyed the neighborhood was just one of a shocking list of wrongs for which the city of San José formally apologized in late September, marking the first time in roughly 130 years that the city has documented its historical role in the adoption of anti-Chinese policies. .

The apology and resolution, read by San José Mayor Sam Liccardo, came as the city searched for ways to respond to the rise in anti-Asian hatred over the past year.

Hate crimes reported against Asians in 16 of the country’s largest cities and counties rose 164% in May 2021, compared to May of the previous year, according to a study by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism of the United States. Cal State University-San Bernardino. .

Through listening sessions in San José, community members raised the idea of considering the city’s past.

“It’s a great, great sense of justice,” said Young Yu.

Smoldering racism leads to arson

The apology and resolution describe a time when San José’s critical agricultural and rail industries depended heavily on Chinese immigrant labor, while anti-China conventions were held in the city.

He goes on to list the ways in which San José played a role in anti-China violence: the city had condemned all Chinese laundries, declared its Chinatown of Market Street as a public nuisance and, when arsonists set it on fire. , refused permission for the Chinese to rebuild in another location.

Young Yu’s grandfather, Young Wah Gok, was part of the community. She told CNN he immigrated to San Jose when he was 11 from a village in southern China, joining Market Street Chinatown, a base for Chinese immigrants.

His grandfather had told him about his fun adventures, like when a player called him to the table and said, “You pick these numbers for me.” Here he is, a kid who just arrived from China after a few weeks, and he picks the winning numbers. “

But the stories of racism and harassment Young Yu later learned from his father: how his grandfather was chased by white boys in the neighborhood where he worked as a house boy, how stones were thrown at him.

An atmosphere of hatred reigned when San Jose City Council condemned Chinatown on Market Street.

Young Yu said there were “people coming into Chinatown with, I guess, orders, saying you know you have two weeks. And there was this feeling already that Chinatown … . that they should go, but they always had the hope that they could fight it. But I don’t think they expected a fire. “

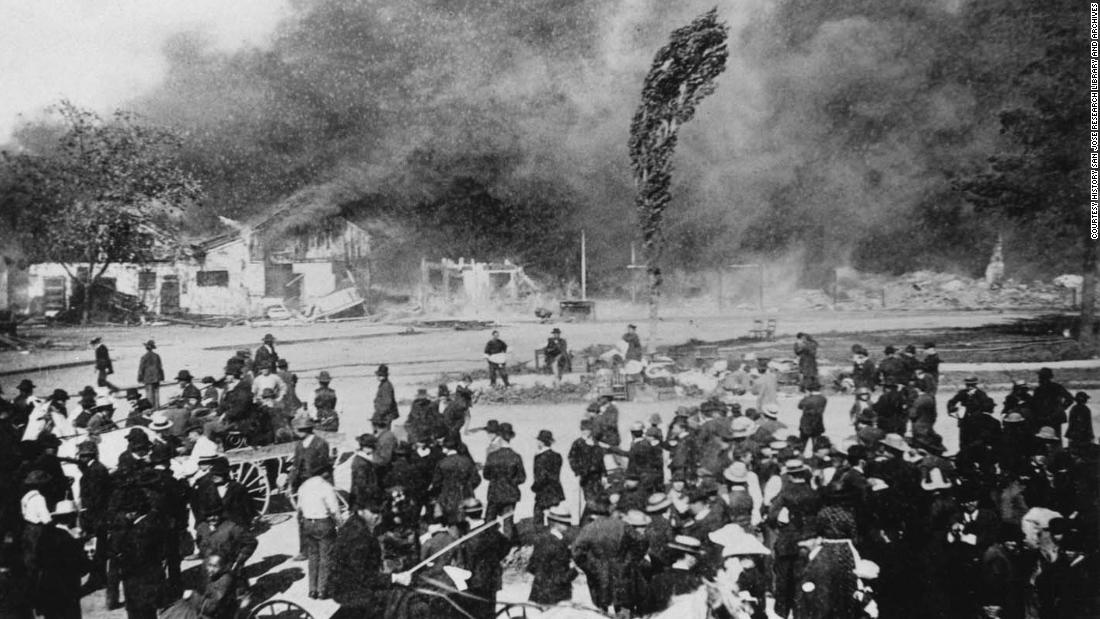

A San Francisco Daily Examiner article on the arson called it “The Joy of San Jose” and a “Gala Day in San Jose”.

A photograph of the blaze shows crowds gathered to watch. Another shows the after-effects of collapsed buildings as spectators pass by. Young Yu said the water tower, which was always full, had somehow been emptied, making it almost impossible to fight the fire.

“It was really a feeling of doom. Because after the fire, so what? Will they come after the individual?” said young Yu.

Rebuilding in the Age of Anti-Chinese Politics

The Chinese immigrants in San José had an ally in John Heinlen, a German immigrant. Shortly after the fire, Heinlen helped the Chinese community rebuild their property, a neighborhood that is now Japantown in San Jose.

But it met resistance from the city, which declared the requested permits “out of order”.

In fact, a demonstration broke out near his property, where a resolution drafted by the mayor and city council stated that a Chinatown would be “a public nuisance, detrimental to adjacent private property, dangerous to health and welfare. to be of all citizens who live and have homes in its vicinity, and a permanent threat to public and private morals, peace, tranquility and good order, etc. ”

Despite vehement opposition, Heinlen completed construction of “Heinlenville”, San José’s last Chinatown, which lasted until 1931.

The events in San José were not isolated. During the 1870s, an economic depression in the United States prompted Chinese immigrants to become scapegoats. In October 1871, a mob of rioters in Los Angeles hanged 18 Chinese immigrants after one allegedly killed a popular saloon owner. In September 1885, white miners in Wyoming, led by the Knights of Labor, killed 28 Chinese and injured at least 15. And in November 1885, a mob of whites in Tacoma, WA, led by the mayor and supported by the police town, invaded Tacoma’s Chinatown and ordered its residents to leave town.

All of these events occurred in the context of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first and only federal law to prevent a specific nationality of people from becoming U.S. citizens for more than half a century.

Due to the law, Young Yu’s grandfather never became a naturalized US citizen. He was not allowed to do so until 1943, just a few years before his death.

Artifacts found a century later

About 100 years after the Market Street Chinatown arson, people who were starting construction on the new Fairmont hotel in San Jose discovered artifacts underground.

When toothbrushes, ceramic kitchen utensils, and whiskey bottles surfaced, the Chinese Historical and Cultural Project was formed to house the objects in a new museum.

Gerrye Wong, one of the organization’s co-founders, taught at a public school in California for 30 years, but never found any mention of the anti-Chinese events in any text or program on California history. .

“I grew up in the city of San Jose, but I didn’t know anything about the five Chinatowns that were here,” Wong said. “So finding pieces like this was like opening up a horizon on the lives of these people.”

In 1991, the Chinese American Historical Museum opened in a building designed to be a replica of the last existing structure in Heinlenville called Ng Shing Gung. The original building was a school, temple, gathering place, and even a hotel for Chinese visitors who weren’t allowed to rent a hotel room elsewhere.

Ng Shing Gung is also mentioned in San Jose’s apology, as the city recognizes its role in destroying the structure and damaging its ornate altar, as it has been stored outside under the municipal stadium for decades. decades.

Wong’s father tried to save the building in the 1930s.

But she said the city of San José “took it by eminent domain and destroyed the building, which was very overwhelming for my father,” Wong said. “But it was also a revelation for me, because how did I start to think about building a replica of this building, not knowing that he had tried to save it 30 years ago?”

After careful restoration, the original altar is now on the second floor of the museum. Wong said she enjoys showing the story to school children on field trips, which she has never been able to do as a teacher in a classroom.

Leadership sets the tone, yesterday and today

Council member Raul Peralez, whose district includes former Heinlenville, was also unaware of the gruesome details of the town’s past prior to this resolution.

As the city tried to fight the surge in emerging anti-Asian hatred with the coronavirus, “one of the things we wanted to do was just bring the community together and find out what more we could do to be in. able to provide some support, and specifically to make statements as a city as a local government here, ”Peralez said.

And statements matter.

Peralez said former President Trump’s rhetoric during the pandemic encouraged people to engage in vicious anti-Asian attacks, both verbal and physical. Likewise, the leadership of San José in the 1880s, he said, set the tone for racist acts.

“We have to learn our history, right? Or we are doomed to repeat it,” Peralez said.

With the apology officially on the city record, attention now turns to a development under construction on the land where Heinlenville once stood. In the center, will be a new Heinlenville park.

Young Yu will be involved in the development of medallions and plaques there, to explain what happened centuries ago.

“It’s a feeling of overcoming,” she said.

[ad_2]

Source link