[ad_1]

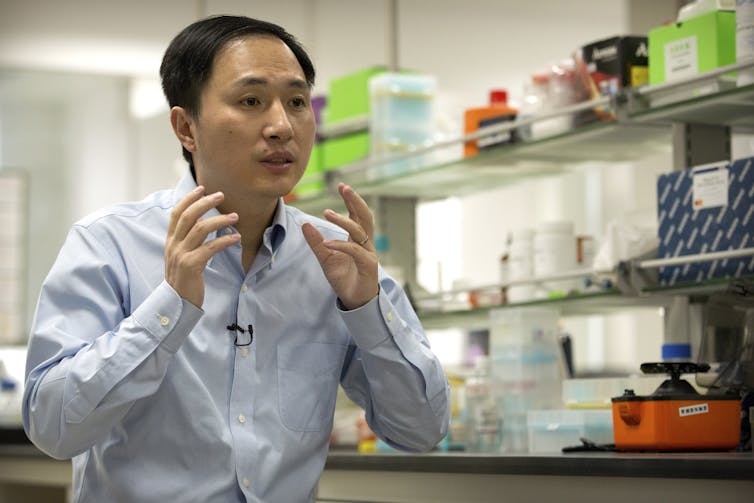

The idea of scientists tinkering with the genes of babies was once the origin of science fiction, but it is now entering the realm of reality: On November 26, Chinese scientist He Jiankui recounted live births binoculars whose genes he had edited. The goal may have been noble: to use CRISPR to modify their genes to include a variant of protection against HIV transmission. But the announcement – which remains to be verified – quickly became entangled in a deluge of scientific and ethical criticism of him as a reckless researcher who oversteped well-established boundaries.

Professional Indignation

The response of the professional community of scientists and ethicists has been rapid and essentially universal, including by more than 100 of its colleagues in China.

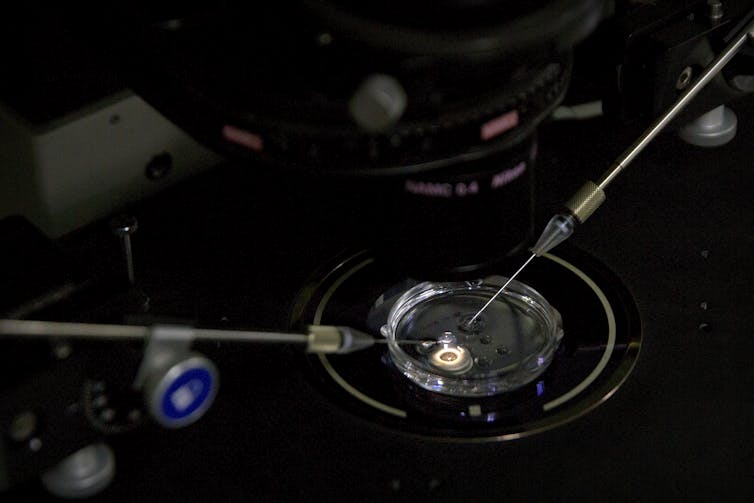

A central objection is that the study was simply too risky. The researchers pointed out that the risk of untargeted effects (involuntary modification of other genes) and mosaicism (modification of the target gene in some cells of the child rather than in the whole of these) could have unexpected and harmful effects on health, such as cancer at a later date. life. It is generally accepted that at present, these risks outweigh the potential benefits and that more fundamental research is needed before proceeding.

It is interesting to note that some of the strongest ethical objections to the experiment were emitted by ethicists who defended gene editing. Julian Savulescu, for example, went so far as to say that if it were safe and not too expensive, we would even have the obligation to change the genes of our children. Yet, he described the reported experience as "monstrous", in light of the serious risks and the lack of necessity. The twins have never risked inheriting a deadly genetic disease and there are far less risky ways to prevent HIV transmission.

Perception of Public Opinion

He may have been surprised by his reaction. According to a report, he would have ordered a large-scale opinion poll in China a few months before the announcement. The survey found that more than 70% of the Chinese population was supportive of the use of gene editing for HIV prevention. That's roughly consistent with a recent Pew poll in the United States that found that 60% of Americans support the use of genetic modification on babies to reduce the risk of contracting certain diseases in their lifetime .

But polls reveal only part of the story. The same Chinese poll also revealed that the public misunderstood gene editing and did not mention the details of He's study. The abstract questions of the polls ignore the risks and the state of science, which were essential to most of the objections to He's experience. This also obscures the involvement of embryos in gene editing. In the US Pew poll, despite support for gene editing, 65% opposed embryo testing – a necessary step in the process of gene editing for treat diseases.

In addition, polls are a crude and simplistic way to participate in a public debate. deliberation on the controversial issue of gene editing.

Various organizations, such as the National Academies of Science, Medicine and Engineering in the United States and the Nuffield Council on Bioethics in the United Kingdom, have pointed out that for gene editing can be subjected to human trials, a thorough public debate is first necessary. to establish its legitimacy.

However, he decided to proceed as transparently as possible, hiding his study from the public, his colleagues, and his institution, even going so far as to prohibit participants from sharing with anyone it is their participation in the trial. under penalty of pecuniary sanction.

His imprudence, therefore, was not limited to risk, but also lacked public confidence and badent before proceeding.

Consent and Incitement

The consent process was another failure of his experience. The study recruited couples with an HIV-positive husband and an HIV-negative woman. On the surface, couples had a special interest in ensuring that their children never get HIV, in light of the father's experience. But a little closer reveals other more problematic motivations.

For such couples, it is possible to conceive HIV-negative children using robust IVF procedures. Such therapy is expensive, prohibitive for many couples. But her study offered a particularly attractive carrot-free IVF treatment, supportive care, per diem and insurance coverage during treatment and during pregnancy. According to the consent form, the total value of salaries and payments amounted to about $ 40,000, four times the average annual salary in urban China.

This raises a serious problem of undue inducement: to pay research participants such an important sum that it distorts their badessment of the risks and benefits. In this context of gene editing, where the risks are incredibly uncertain and where the general understanding of genetics and gene editing is greatly limited, the company should be particularly concerned about the effect distortion of such an important reward on the provision of free and informed consent of participants.

Aftermath

In a video announcing the birth of the twins, he announced that he was ready to badume full personal responsibility for the conduct and results of the l & # 39; 39; experience. And indeed, the consequences of this unethical experience are already accumulating. His own university disavowed him, after having suspended him before, while many investigations were ongoing on him, his American collaborator and the hospital ethics committee who approved the experiment. .

The result of these surveys remains to be seen, but it remains part of a disturbing pattern in reproduction: rogue scientists forcing international standards to engage in ethically and scientifically questionable research. In fact, over the past two years, another group of renegade scientists has been flaunting established standards to create the first three-parent IVF babies; there has been an outcry, but the procedure seems to continue in the relatively lax regulatory framework of Ukraine.

Scientists, ethicists, policymakers and the general public are now struggling to find a way to reverse this trend. bring reproductive medicine back to the path of responsible research and innovation

G. Owen Schaefer, Assistant Professor of Biomedical Ethics at the National University of Singapore

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link