[ad_1]

Metal shrapnel flying faster than bullets; the space shuttle shattered into pieces; astronauts killed or ejected in space. Guilty party? Space debris – debris from a Russian satellite destroyed by a Russian missile. The only survivor, Ryan Stone, must find his way back to Earth with a failed oxygen supply and the nearest viable spacecraft hundreds of miles away.

On Mars, 20 years later, a mission of 39, exploration of the Earth. An epic dust storm forces the crew to abandon the planet, leaving behind an astronaut, Mark Watney, presumed dead. He must find how to grow food while waiting to be saved.

Hollywood knows how to terrify and inspire us about space. Movies like Gravity (2013) and The Martian (2015), present the space as hostile and unpredictable, danger of spelling for any intrepid human who dares s & d To venture out of the hospitable limits of the Earth. Matt Damon in The Martian. Credit: Pe3k

This is only part of the story, however, the little with the people at the center of the scene. Of course, no one wants to see astronauts killed or stranded in space. And we all want to enjoy the fruits of a successful planetary science, like determining which planets could host human life or simply if we are alone in the universe.

Valuing the Space

But Should We Care? about the universe beyond how it affects us as human beings? That's the big question – call question # 1 of extraterrestrial environmental ethics, a field too many people have ignored for too long. I am part of a group of researchers from the University of St Andrews who is trying to change that. The way in which we must evaluate the universe depends on two other intriguing philosophical questions:

Question # 2: The kind of life that we are most likely to discover elsewhere is microbial – so how should we see this form of life? Most people would accept that all human beings have intrinsic value, and are not only related to their utility for someone else. Accept that and it follows that ethics imposes limits on how we can treat them and their living spaces.

People are beginning to accept that the same goes for mammals, birds and other animals. So what about microbial beings? Some philosophers like Albert Schweitzer and Paul Taylor have already argued that all living things have intrinsic value, which obviously includes microbes. However, philosophy as a whole has not yet reached a consensus on its agreement with this so-called biocentrism.

"What do we want, rights for microbes?" Credit: Who is Danny

Question # 3: For planets and other non-hospitable places to life, what value should we give to their environment? We can say that we care about our environment on Earth mainly because it supports the species that live here. If so, we could extend the same thought to other planets and moons that can sustain life.

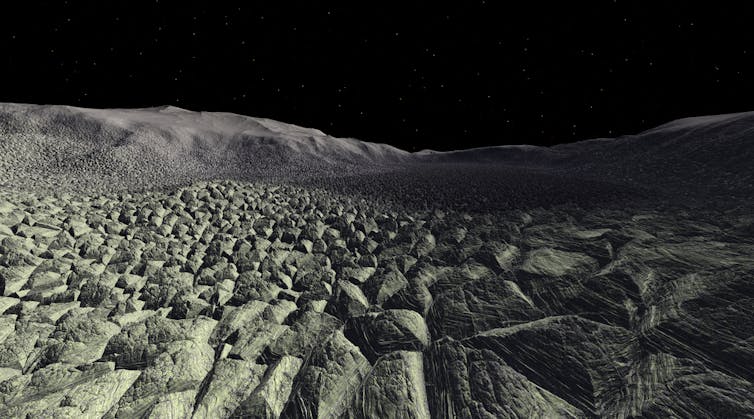

But that does not work for "dead" planets. Some have come up with an idea called aesthetic value, namely that certain things should be appreciated not because they are useful, but because they are aesthetically wonderful. They applied it not only to great works of art such as Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa and Beethoven's Fifth, but also to parts of the Earth's environment, such as the Grand Canyon. Assuming that we can answer these theoretical questions, we could move on to four important practical questions on space exploration:

Question 4: Is there a duty to protect the environment on the ground? Other planets? When it comes to sending astronauts, instruments or robots to other worlds, there are obvious scientific reasons to make sure that they do not carry d & rsquo; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; & nbsp; Terrestrial organisms and end up laying them there.

Otherwise, if we discover life, we do not know if it was indigenous – not to mention the risk of completely annihilating it. But is scientific clarity all that matters, or should we start thinking about protecting the galactic environment?

Question 5: What is the violation of such an obligation to treat the environment of the planet? Drill carrots, perhaps, or leave behind instruments, or put tire tracks in the ground?

Question # 6: What about asteroids? The race is well underway to develop a technology to harvest the innumerable billions of pounds of mineral wealth believed to exist on asteroids, as already reported in The Conversation . This helps that no one seems to regard asteroids as environments that we must protect.

Gold in the craters. Credit: Jan Kaliciak

The same goes for empty space. The film Gravity gave us some human-centered reasons for worrying about the accumulation of debris in the space, but could there be any problems? 39, other reasons to object? If so, would our obligation simply be to create less debris, or something stronger – such as not producing new debris or even cleaning up what we left behind?

Question 7: What considerations could offset arguments in favor of ethically behavior in space? Among the various reasons to go there – intellectual / scientific, utilitarian, profit oriented – are they strong enough to exceed our obligations?

We must also take into account the risks and uncertainties that are inevitable here. We can not know what space missions will serve. We can not be sure of not biologically contaminating the planets we visit. What trade-offs between risk and reward should we be willing to undertake?

Terra-ism

The discussions on the space have the advantage that we have very little attachment to anything. These ethical questions could be the only ones that humans can approach with a great emotional distance. Answering these questions could help us move forward on Earth-related issues like global warming, mbad extinction and the disposal of nuclear waste.

Space exploration also raises questions about our relationship to the Earth. terraforming a planet like Mars, or finding ways to reach habitable exoplanets. I leave you with an extremely important for the future:

![]() Question # 8: Since the Earth is not the only potential home for human beings, what reasons to protect his environment would be to stay once we can reasonably go elsewhere

Question # 8: Since the Earth is not the only potential home for human beings, what reasons to protect his environment would be to stay once we can reasonably go elsewhere

B Jamin Sachs is Lecturer in Philosophy, University of St Andrews.

This article was originally published on The Conversation . Read the original article.

![]()