[ad_1]

During my career as a zoo keeper, I had the privilege of working with the tigers of Sumatra and Love. If they did not both have stripes, one would think that they are totally different species.

The Sumatran tiger is the smallest living in the world. At around 100 kg, it's "only" about the weight of a tall adult man. It is suitable for the hot and humid forests of the Indonesian island of Sumatra, which is reflected in its smaller size and its short, dark rust-orange coat which features many thin black bands to conceal it in the dense vegetation of their prey.

The Love Tiger, or Siberian, is much larger and weighs an average of 170 kg (although historical reports indicate that males reach 300 kg or more) and are now found mainly in the wild. one of the corners of the far east of Russia. It has a thicker but relatively pale coat, with thin dark brown stripes, allowing it to survive in icy and snowy winters.

Tiger experts have long debated the scientific significance of such differences. Should the biggest cat be divided into several subspecies, or are all tigers just "tigers"?

This is a problem that has serious consequences for conservation. About 3,500 tigers remain in the wild, in only 7% of their former range. And if these tigers are all identical, or if most of them are identical, saving a little less each population matters less – and tigers can be moved to facilitate breeding in the wild.

tom177 / shutterstock

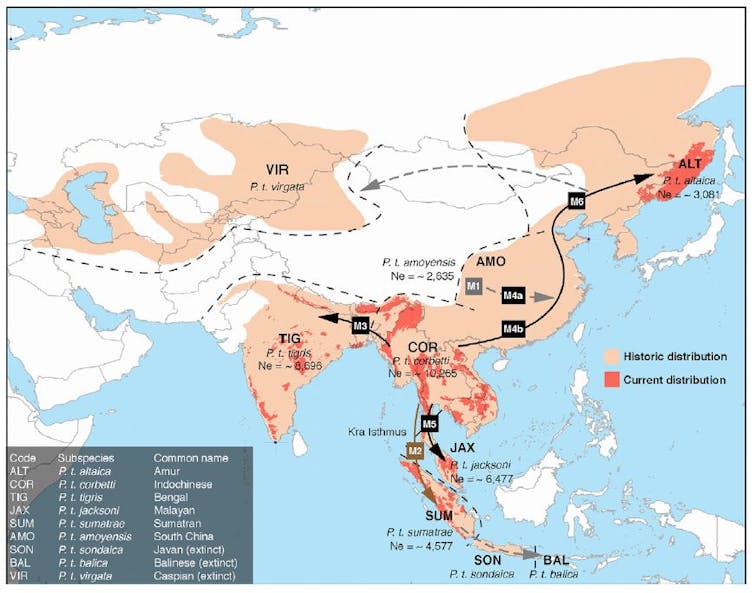

Traditionally, eight subspecies were considered extant. These are the two already mentioned, plus the Bengal tiger, which is found mainly in India, the Indochinese, the South China tiger, then three extinct subspecies: Bali (extinct in the 1940s) and Javan ( 80 years old), both closely related to surviving tigers. in Sumatra and the Central Asian Caspian Tiger, which died in the 1970s.

As genetic techniques evolved, a 2004 study found that genetic diversity in tigers was low, but sufficient to support the separation of subspecies. He also suggested that the Indochinese tigers living on the Malay Peninsula were sufficiently different from those living further north to justify the creation of a ninth subspecies: the Malayan tiger.

These ideas were challenged by a group of researchers in 2015, who argued that the relative lack of variation among the continental Asian subspecies and the large overlaps in shape, size, and ecology meant that all the tigers from India to Siberia or Thailand were to be considered the same subspecies. Researchers have named only two recognized subspecies: the continental tiger and the Sunda tiger, found on various Indonesian islands.

However, the different subspecies are clbadified. One of the constant results is that tigers follow the Bergmann rule: a zoological principle that states that animals belonging to the same species will tend to be larger in colder environments and vice versa. The Love Tiger, for example, takes advantage of the fact that larger animals retain heat better because they have a smaller surface area than their total mbad.

Six Genetically Separate Groups

It is at this point that a new study published in the journal Current Biology incorporates it. Chinese and American researchers examined the entire genome of 32 representative tigers and found that there were actually nine subspecies of tigers. – six survive today. But their work also shows that the various adaptations to temperature – tall and hairy Amur, small and elegant Sumatra – were triggered by important prehistoric events that altered global and local temperatures.

Liu et al. / Current Biology, CC BY-SA

The results support previous hypotheses that the low genetic diversity of tigers was caused by a population decline during an ice age 110,000 years ago. Thousands of years later, the first separation between a single ancestor species occurred between insular and continental subspecies, the former becoming smaller through natural selection. The super eruption of the Sumatra Toba volcano 75,000 years ago, followed by a period of extreme cooling was the probable cause. Subsequent divisions of more specialized tigers reflect other important extreme climatic changes.

This Affects Conservation Tactics

So why is it important in terms of tiger conservation? As previous research has shown, the lack of genetic and morphological differences between tigers on the mainland could allow them to be managed as a single subspecies. Theoretically, individuals from any region, wild or captive, could be relocated to repopulate old areas or increase the number of failed local populations. This could help to increase the overall number of tigers and local genetic diversity.

Vaclav Sebek / shutterstock

But the recent study suggests that adaptations of the tiger might be more subtle and more complex than before. If tigers are allowed to hybridize in captive or wild populations, the most vulnerable subspecies may disappear before we fully understand how they adapted to their area.

It is disadvantageous to regard tigers as a distinct subspecies and to attempt to protect them on this basis, without mixing them with other tigers. The number of each subspecies is very small – there are only about 500 wild Amurs – and smaller populations are more vulnerable to extinction. This could be caused by regular threats of habitat loss and poaching or simply by the reduction of genetic diversity making a small population vulnerable to diseases and other selective pressures.

Genetic diversity is essential for adaptation and ultimately for species survival. As our understanding grows, more informed decisions can be made about the best way to conserve the tiger. We may not have enough time to solve all the puzzles, but it may be a step further to ensure that one of the most iconic animals in the world does not disappear forever.

Source link