[ad_1]

In cities, air, surface and ground temperatures are almost always warmer than in rural areas, writes Gerald Mills – Lecturer in Geography, University College Dublin . Urban Heat Island – a term that came into effect in the mid-20th century. Until the 1980s, this effect was considered to have relatively little practical significance. In fact, since most studies were conducted in cities with cold winter weather, higher temperatures were considered a potential benefit because they reduced the need for heat. But since then, we have found a number of reasons to worry.

On the one hand, it became clear that the effect of urban cities on heat islands influences the air temperature readings used to badess climate change. . In other words, it became important to remove urban "contamination" from weather station records to ensure accuracy.

What's more, populations in warm, hot cities have increased, as has the demand for indoor cooling. This applies even in colder climates, where the changing uses of the building has increased the demand for cooling; for example, in office buildings, to offset the heat generated by computers.

In these situations, the ICU adds to the heating load: Ironically, cooling buildings with air conditioners increases outside air temperatures. kill; for example, during the 2003 heat wave in Europe, additional deaths were recorded, making it one of the most deadly natural disasters in the region over the past 100 years. The UHI makes city dwellers more vulnerable to the dangerous effects of extreme weather events like this one.

The potential medical impact is perhaps the most important problem related to ICU, especially in the context of climate change and global warming. For all these reasons, it is crucial to understand the operation of the UHI, in order to find ways to mitigate and adapt to its effects.

Understanding the UHI

The UHI is the strongest during dry periods, when the weather is calm and the sky is clear. These conditions accentuate the differences between urban and rural landscapes. Cities are distinguished from natural landscapes by their form: that is, the extent of urban land cover, the building materials used and the geometry of buildings and streets. All of these factors affect the exchange of natural energy at ground level.

Much of the urban landscape is paved and devoid of vegetation. This means that there is usually little water available for evaporation, so most of the available natural energy is used to warm the surfaces. Building materials are dense and a lot – especially dark colored surfaces like asphalt – absorb and store solar radiation well.

There are however different types of ICU, with different leading causes.

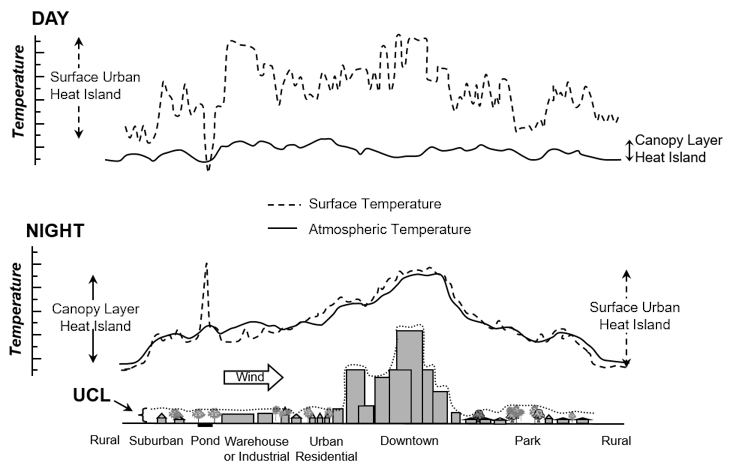

] "Surface UHI" refers, unsurprisingly, to warmer urban temperatures on the surface of the Earth. Typically, this type of UHI is measured using satellites with a plan view of the city, so the temperature of the roofs and roads (but not the walls) can be measured. From this point of view, the UHI surface is highest during the day, when hard urban surfaces receive solar radiation and warm up quickly.

Another type of UHI is based on observations of the temperature of the air. in the city, it means placing the instruments under the roof. This UHI is usually the strongest at night, as street surfaces and adjacent air cool slowly. Above the roof level, the contributions of the streets and roofs of buildings warm the overlying urban atmosphere. Under certain conditions, this warming can be detected up to 1km to 2km above the surface.

The Geography of the Island of Urban Heat. Jamie Voogt, University of Western Ontario, Author Provided

The geography of the ICU is relatively simple – its magnitude generally increases from the urban periphery to the city center. However, it also contains many microclimates – for example, parks and green spaces appear as cool spaces.

The ISU is an inevitable result of the changes in the landscape that accompany urbanization. But its scale and impacts can be managed by modifying some physical aspects of our cities. This can include increasing the vegetation cover and reducing the impervious cover; use lighter colored materials, design urban developments to allow better ventilation across streets and buildings, and manage urban energy consumption.

Of course, these solutions must be adapted to the type of ICU. For example, the emphasis on building fresh or green roofs will impact the overlying air and the top floor of the buildings, but could have little impact on the building. UHI at the street level. Similarly, trees can be an effective way of providing shade to the street, but if the canopy surrounds the street, it can trap traffic emissions, resulting in poor air quality.

"hot spots", where design interventions might have the greatest effect. But most cities need a coherent climate plan, which addresses interdependent environmental issues, including floods and air quality, as well as surface and air temperatures. .

Conversation

Read the original article here.

Source link