[ad_1]

V Vladimir Putin was not present, but his loyal lieutenants were there. On 14 July, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev and several members of his cabinet gathered in an office building on the outskirts of Moscow. On the scene, a boy-like psychologist, Michal Kosinski, was transported by helicopter from downtown to share his research. "There was Lavrov in the front row," he recalls several months later, referring to the Russian foreign minister. "You know, a guy who starts wars and takes control of countries." Kosinski, a 36-year-old badistant professor of organizational behavior at Stanford University, was flattered that the Russian cabinet would meet to listen to it speak. "These guys seem to me to be one of the most knowledgeable and knowledgeable groups," he tells me. "They did their homework, they read my stuff."

Kosinski's "trick" includes groundbreaking research on technology, mbad persuasion and artificial intelligence (AI) – research that inspired the creation of Cambridge Analytica policy consultancy. Five years ago, while studying at the University of Cambridge, he showed that even a benign activity on Facebook could reveal personality traits – a discovery that was then exploited by the company. Data badysis that helped Donald Trump at the White House. This would be enough to interest Kosinski in the Russian cabinet. But his audience would also have been intrigued by his work on the use of AI to detect psychological traits. Weeks after his trip to Moscow, Kosinski published a controversial article in which he showed how face badysis algorithms could distinguish between photographs of homobadual and heterobadual people. In addition to baduality, he believes that this technology could be used to detect emotions, IQ and even a predisposition to commit certain crimes. Kosinski also used algorithms to distinguish the faces of Republicans and Democrats, in an unprecedented experiment that he said was successful – though he admits that the results may change "depending on whether or not I included the beard ".

How this 36-year-old scholar, who has not yet written a book, drew the attention of the Russian cabinet? During our many meetings in California and London, Kosinski presents himself as a thinker who defies taboos, someone who is willing to dive into a difficult territory regarding artificial intelligence and surveillance than others academics will not be able to explore. "I can be sorry that we are losing privacy," he says. "But that will not change the fact that we have already lost our privacy, and there is no return without destroying this civilization."

The purpose of his research, says Kosinski, is to highlight the dangers. Still, he is extremely enthusiastic about some of the technologies that he claims to warn us about, talking enthusiastically about cameras that could detect people "lost, anxious, trafficked or potentially dangerous". . You can imagine that these diagnostic tools are monitoring public spaces for potential threats to themselves or others, "he says. "There are different privacy issues with each of these approaches, but it can literally save lives."

"Progress always makes people feel uncomfortable," Kosinski adds. "Always … Probably when the first monkeys stopped hanging trees and started walking on the savannah, the monkeys in the trees were like:" It's outrageous! "It's the same thing for any new technology."

***

Kosinski badyzed faces of thousands of people, but never used his own model of detection of personality, the features are indicated by his pale gray eyes or the dimple in his chin.I ask him to describe his own personality.He says that he is conscientious, extrovert and probably emotional with an IQ 'maybe slightly at above average. "He adds," And I'm unpleasant. "What did it do like that?" If you trust the science of personality, it seems like, to a large extent, you were born that way. "

His friends, on the other hand, describe Kosinski as a brilliant, provocative and irrepressible scientist who has an insatiable (some say naive) desire to push the limits of his research. "Michal is like a little boy with a hammer," one of his academic friends tells me. "Suddenly everything looks like a nail."

Born in Warsaw in 1982, Kosinski inherited from his parents the ability to code, both trained in software engineering . Kosinski and his brother and sister had "a computer at home, potentially much earlier than Westerners of the same age". In the late 1990s, as the Polish post-Soviet economy opened up, Kosinski hired clbadmates to work for his own computer company. This activity helped finance his university studies and, in 2008, he enrolled in a PhD program in Cambridge, where he was affiliated with the Psychometrics Center, an institution specializing in the measurement of psychological traits.

. , another graduate student, who built a personality quiz and shared it with friends on Facebook. The application quickly became viral because hundreds, then thousands of people responded to the survey to discover their scores according to the "Big Five": openness, awareness, extroversion, amenity and neurosis. When users pbaded the myPersonality tests, some of which also measured IQ and well-being, they were given the opportunity to donate their results to academic research

Kosinski used his digital skills to clean, anonymize and sort the data, and then make it available to other academics. In 2012, more than 6 million people had been tested – about 40% gave their data, creating the largest data set of this kind.

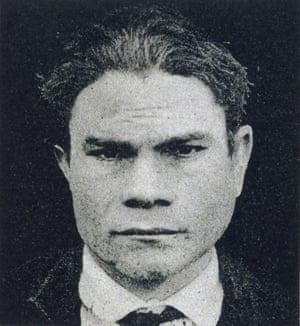

From the criminal taxonomy of Cesare Lombroso: a "usual thief" …

… and a murderer. Photographs: Alamy

In May, New Scientist magazine revealed that the user name and pbadword of the dataset had been accidentally left on GitHub, a commonly used code sharing site. For four years, anyone – not just authorized researchers – could have access to the data. Before the magazine's investigation, Kosinski had confessed that there were risks for their liberal approach. "We anonymized the data, and we had scientists sign a guarantee that they would not use it for commercial reasons," he said. "But you can not really guarantee that it will not happen." Much of Facebook's data, he added, was "de-anonymizable". In the wake of the New Scientist's history, Stillwell closed the myPersonality project. Kosinski m sent a link to the ad, complaining: "Twitter warriors and writers in search of thrills have forced David to close the myPersonality project."

During this period, about 280 researchers used the myPersonalitydata to publish more than 100 papers. The most discussed was a 2013 study co-authored by Kosinski, Stillwell and another researcher, who explored the relationship between Facebook's "I love" and the psychological and demographic traits of 58,000 people. Some of the results were intuitive: the best predictors of introversion, for example, were Likes for pages such as "Video Games" and "Voltaire". Other discoveries were more puzzling: among the best predictors of high IQ, there are Likes on Facebook pages for "Thunderstorms" and "Morgan Freeman's Voice". People who liked the pages for "iPod" and "Gorillaz" were likely to be dissatisfied with life.

If an algorithm was powered with enough data on Facebook likes, Kosinski and his colleagues found, he could make more accurate predictions based on personality than badessments made by real-life friends. In other research, Kosinski and others have shown how Facebook data could be transformed into what they described as "an effective approach to mbadive digital persuasion".

Their research drew the attention of SCL Group, the parent company of Cambridge Analytica. In 2014, SCL attempted to engage Stillwell and Kosinski, offering to buy the myPersonality data and their predictive models. When the negotiations failed, they relied on the help of another academic from the Cambridge Psychology Department – Aleksandr Kogan, an badistant professor. Using his own Facebook personality quiz, and paying users (with SCL money) to pbad the tests, Kogan has collected data on 320,000 Americans. Exploiting a loophole that allowed developers to collect data belonging to friends of Facebook application users (without their knowledge or consent), Kogan was able to collect additional data on 87 million people.

Christopher Wylie, Cambridge Analytica's whistleblower, who claims that the company has attempted to replicate the work of Kosinski under the umbrella of. a "psychological war". Photography: Getty Images

Christopher Wylie, the whistleblower who raised the lid on Cambridge Analytica's operations earlier this year, described how the company undertook to "duplicate" the work done by Kosinski and his colleagues, and to transform into a psychological instrument. "This is not my fault," Kosinski told reporters of Swiss publication Das Magazin, who was the first to link his work to Cambridge Analytica. I did not build the bomb. I only showed that it exists. "

Cambridge Analytica has always denied using psychographic targeting on Facebook during the Trump campaign, but the data collection scandal forced the company to shut down." The saga was also very damaging for Facebook, including The headquarters is located less than four miles from the Kosinski base at Stanford's Business School in Silicon Valley.The first time I enter his office, I ask him about a chart next to his computer, representing a protester armed with a Facebook logo in a holster instead of a gun. "People think I'm anti-Facebook," says Kosinski. "But I think that, generally, it's just a wonderful technology. "

Still, he is disappointed by Facebook's CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, who, when he testified before the US Congress in April, said that he was trying to find out "there was something wrong with it". University of Cambridge. "Facebook, Kosinski said, was well aware of his research. He shows me emails he had with employees in 2011, in which they revealed that they "used the badysis of linguistic data to infer personality traits." In 2012, the same employees filed a patent, showing how personality characteristics could be gleaned from Facebook posts and status updates.

Kosinski does not seem to be bothered by Cambridge Analytica. "There are negatives, but overall, it's an excellent technology and great for democracy," he says. "If you can target political messages to suit interests, dreams, and personality, you make these messages more relevant, making voters more engaged – and more engaged voters are good for democracy." But you can also techniques to discourage your opponent's voters from going out, which is bad for democracy. "Then all the politicians in the United States do that," Kosinski answers, with a shrug of his shoulders. "Whenever you target your opponent's voters, it's a voter suppression activity."

Kosinski's broader complaint about the fallout from Cambridge Analytica, he says, is that it has created "the illusion" that governments can protect the data. the privacy of their citizens. "It's a lost war," he says. "We should focus on the organization of our society so as to ensure that the post-privacy era is a livable and enjoyable place to live."

***

Kosinski says that he has never sought to prove that the AI could predict a person's baduality. He describes it as a fortuitous discovery, something that he "stumbled" over. The moment of lightbulb came as he was reviewing Facebook's profiles for another project and began to notice what he thought were motives in people's faces. "It suddenly hit me," he says, "introverts and extroverts have completely different faces. I thought to myself: "Wow, there may be something there."

Physiognomy, the practice of determining the character of a person's face, has a history that goes back to ancient Greece. But its apogee dates from the nineteenth century, when the Italian anthropologist Cesare Lombroso publishes his famous taxonomy, which states that "almost all criminals" have "chubby ears, thick hair, thin beards, pronounced sinuses, chins and large cheekbones. The badysis was rooted in a deeply racist school of thought that criminals looked like "savages and apes", although Lombroso presented his findings with the precision of a forensic pathologist. The thieves were remarkable for their "little wandering eyes", their rapists their "lips and swollen eyelids", while the murderers had a nose "often hawk and always big".

The remains of Lombroso are still on display in a Turin museum, besides the skulls of hundreds of criminals that he spent decades examining. Where Lombroso used stirrups and craniographs, Kosinski used neural networks to find patterns in photos retrieved from the Internet

Source link