[ad_1]

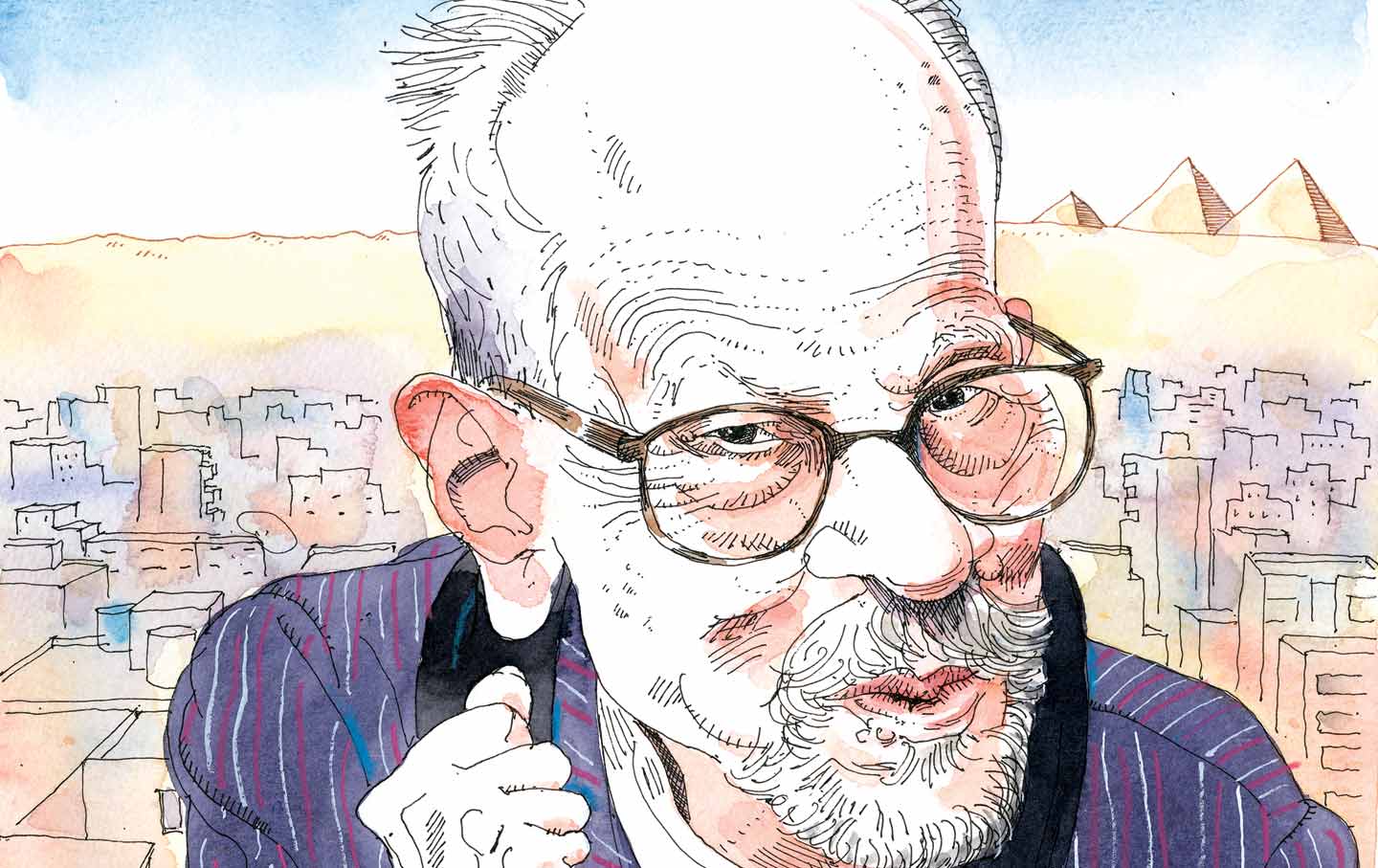

I put Naguib Mahfouz ounce. It was in the winter of 2006, and I'd been living in Cairo for three and a half years. The writer Gamal Al-Ghitani, an old friend of Mahfouz's, provided me with an introduction to one of his weekly gatherings. I went to a Holiday Inn in the suburb of Maadi. The hotel faced the Nile across four lanes of traffic. There was a metal detector at the front door. Ever since he was a victim of a fundamentalist in 1994, Mahfouz no longer frequented the downtown cafes where he had met friends and fellow writers for half a century.1

It was a small group; I can not remember any names. There must have been a few of Mahfouz's old friends and a few new admirers such as myself. Also in attendance was a well-known Cairo character, a middle-aged man.2

Mahfouz was 94 then. He was wrapped in an overcoat that was too big for him and made him look like a small, wizened, sympathetic turtle. He was still blind and deaf, and one of his companions sat right next to him and yelled into his ear. His right hand was contracted into a claw, a consequence of the attack 12 years before, when a young man approached while he was sitting in a car, reached in, and stabbed his throat. Because of the way Mahfouz, already elderly, was sitting hunched forward, the would-be murderer just missed his carotid artery.3

That evening at Holiday Inn, Mahfouz had a Turkish coffee and a single cigarette. His pleasure in these rituals, and in the give-and-take of conversation, was obvious. He was surrounded by those who respected him; everyone strived to amuse him, and when he laughed, long and hoarsely, his small, bony face reads up and turned boyish. I think he asked me who my favorite writers were, and told me he admired Shakespeare and Proust. At one point he asked me if I thought his novel Children of the Alley was "against religion"? This was the book whose allegorical retelling of the Bible and the Quran had been deemed blasphemous and had led to the murder attempt.4

Flustered, I answered no, I did not think the book was against religion. I will not forget his wry, slightly disappointed smile. I wish I had said something more honest or more interesting, such as "Even if it is, I do not care."5

Mahfouz signed my copy of The Cairo Trilogy in a labored, gnarled hand. How to write again, but after a few years' reprieve, the atrophy had returned. He died that summer.6

NOTAguib Mahfouz lived for almost a century, and he wrote for most of that time: short stories, plays, scripts for Egypt's booming movie industry, and novels that, serialized in Egypt's leading magazine and newspaper, became clbadics. In 1988, he won the Nobel Prize for Literature; today, he remains the only Arab author to have received that honor.7

It is no exaggeration to say that Mahfouz is one of the artists who helped Egypt's modern consciousness. So much so that when his writing and his temperament is quintessentially Egyptian-his extreme attachment to the country, to Cairo, and to the neighborhood of his birth; his cynicism, caution, and cheerfulness; his love of shisha and Oum Kalthoum and the art of chatting with friends-one is unsure if that is because it has such a hand in this quintessence. It has been said that it has given rise to many Egyptian writers the gift of an entire modern literary legacy, ranging from social realism to existentialism, stream of consciousness, allegory, and black. Yet despite all his experiences in form, he was concerned with his themes: He was concerned with Egypt's national identity and development, with social change, and with what Egypt was and could have been. in Children of the Alley (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb. The coffeehouse, an all-male space where stories are told, gossip and jokes shared, egos ruffled and smoothed. And above all else, the alley, a place he knew from his childhood, his preferred stage for the performance of family, and national dramas-which, for Mahfouz, were all one and the same.8

Yet the Mahfouz who conjured these spaces Essays of the Sadat Era, 1974-1981, the second volume in a series of his nonfiction writing, out of the Gingko Library, which features newspapers published in the flagship state newspaper, Al Ahram, Under the boilerplate title "A Point of View." From his own account, Mahfouz was always engaged in politics: "In everything I write you will find politics," he told Al-Ghitani, who collected their conversations into a book, Majalis Mahfouzia (Meetings With Mahfouz). And in his columns, his politics come through: He is a liberal advocate of personal liberty, almost always a moderate, an advocate of progress and rationalism, and a nationalist.9

What he is not, in these columns, is a writer. The columns are shockingly bbad, almost as if Mahfouz were saving every speck of his gift for his novels. The book's introduction, by Rasheed El-Enany, makes this clear: "One thing the reader misses in reading these collections of Mahfouz's journalism is the beauty of language, the elegance of style, the imagination … "In fact, what the columns largely do is deepen the mystery of Mahfouz 's writing and life, the seeming contradiction between his everyday backing and reticence and his daring literary ambition.10

Mahfouz skillfully navigated censorship throughout his career, and even worked in his own way, and managed to write about Egypt in ways that were bold and true. He was a lifelong government employee, a national icon whose work was serialized in the state of the press, and yet he had a great deal of interest in his country's hopes.11

MAhmadou was born in 1911 and grew up in Al Gamaliya, a historic neighborhood in Cairo, home to thousand-year-old mosques, monumental gates, and tight alleyways. His family supported the Wafd, Egypt's liberal nationalist party, which led to an early struggle for independence from the British; the Wafdist leader Saad Zaghloul was venerated in his home. His father, a government bureaucrat, spoke of family affairs and national affairs "as if they were the same thing," and of Zaghloul, the Egyptian monarchy, and the British as they were "his personal friends and enemies."12

In 1919, the British exiled Zaghloul, and the country erupted in months of prolonged protest. Mahfouz watched from the face of great british demonstrations pbaded through the neighborhood by British troops. Several years later, when Mahfouz was around 12, his family left Gamaliya, relocating to the up-and-coming Abbasiya district. But he returned to his childhood neighborhood, literally and figuratively, for the rest of his life. The world of the alley-a social space, a human stage, and a political allegory would inspire much of his writing.13

In 1922, Egypt was granted nominal independence, and the next year Zaghloul was allowed to return; The British continued to rule the country behind the scenes, propping up Egypt's increasingly weak and unpopular monarchy. Then, in 1952, frustrated by the ongoing English presence and the dissolute lifestyle of King Farouk, a group of young Egyptian officers overthrew the monarchy and declared Egypt a socialist republic. One of these officers, Gamal Abdel Nbader, soon became the country's president. Two years later he was nationalized by the Suez Cbad and became a standard bearer for Arab nationalism throughout the Middle East. Nbader would also institute a single-party system, monopolize the media, and crack down on Islamist and Communist dissenters.14

Mahfouz was 40 at the time of the coup and an established author. It is also very much in the nature of the socialist redistribution policies, but it was also suspicious of military rule and regretted that the liberal politics and democratic aspirations of the 1920s and the Wafd party had not been realized. In fact, he would always view the 1920s as the high point of Egypt's struggle for independence, a time of feverish nationalism and romantic optimism. His famous family saga The Cairo Trilogy in the background of the World War II. Palace WalkThe first book in the trilogy, concludes with Fahmy-the family's golden boy, a promising young man of abilities and principled-cut down by British bullets while marching in a pro-independence protest. His death is a loss from which his family never recovers. The hope for an independent democratic goal Egypt is cut down as well.15

Mahfouz grew up in a home with no literary culture, and he borrowed his first book from a childhood friend. Like other boys in his life, he loved crime and adventure stories, and he began writing in his own life with his favorite paperbacks, inserting a few details from his own life and prominently appending his signature at the end.16

In a sense, many of Mahfouz's novels were a continuation of his childhood hobby of "writing" by copying. He admired the great thinkers of the 1920s and '30s, intellectuals like Taha Hussein and Tawfiq Al-Hakim, and thing to study philosophy at Cairo University under Hussein. After graduating, however, he had a change of heart; he approached his decision to become a novelist with typical determination and discipline, reading nearly all of the West's great novelists and playwrights. His favorites were Shakespeare, Proust, and Tolstoy; he also liked Ibsen, Chekhov, Thomas Mann, and Eugene O'Neill. Hemingway, he thought, was overrated, and Faulkner "more complicated than necessary."17

All art is imitation, but as Mahfouz later noted, the subject is a matter of art.18

The European writer who started when I did, could search for himself from the first day …. [W]e writers who belong to the so-called developing or undeveloped world, we thought that we should establish a true literary self. I mean the European novel form was sacred, to go against it was sacrilegious. That is why I think of the role of the author of the book, because it is a proper and improper way of writing a novel.19

By the 1930s, Mahfouz began to publish stories in magazines and embarked upon an ambitious series of novels set in Egypt's pharaonic times. These books were used in the British occupation, but it was abandoned in the 1940s and turned to contemporary Egypt. It was the right decision. By 1947, when he published the novel Midaq Alley, the key elements of his fiction have been there, starting with the alley of the title. Much of the power of Mahfouz's work-besides the beauty of his prose-comes from the multiple levels of his stories. The alley depicted in them is a dense, socially diverse microcosm in which personal destinies, political conflicts, and social transformations are played out. It is both a recognizable place and a resident of the United States.20

Mahfouz believed that writers and intellectuals should confront and portray reality. In his view, he commented: "The delusion of a number of right-minded people is that of portraying negative sides of life, which is an offense against the reputation of society, and that it is our priority to portray what is aiming to reduce the incidence of violence in the workplace and to reputation."21

Midaq Alley ignores no one: Zaita, who would be beggar the deformities they need to make a living; Kirsha the cafe owner, who refuses to be chastised for his trysts with young men; and above all the headstrong Hamida, a Cairene Moll Flanders, who runs away from home and becomes a prostitute. Mahfouz is also careful to tell their stories from their points of view. "Her nature craved something more," he wrote of Hamida, "than waiting in humble silence."22

Midaq Alley was an badured and vivid work, but it was not until almost a decade later, with the publication of his Cairo Trilogy, that Mahfouz made his reputation. That work, which Mahfouz subdivided into volumes named afterPalace Walk, Palace of Desire, and Sugar Street-begins in 1917, as Amina, the mother of a mid-clbad Cairo family, wakes up at midnight. Awaiting her husband's return, she "entered the closed cage" by the latticework of the latticework of the latticework panels. "From this blinkered point of view, our vision of Cairo gradually expands until we can take in all of Mahfouz's sweeping, intricately plotted panorama. Through hundreds of pages, to new neighborhoods, new generations of Amina's family, new ideas and expectations. Momentous historical, political, and social changes are all refracted through the lives of her children.23

in Palace Walk'S opening, Amina's Husband, Al-Sayyid Ahmad, is returning home after carousing with his friends. He's a successful merchant and a lover of drinking, women, and music. "Mahfouz's portrait of patriarchy-in all" its hypocrisy, cruelty, and charisma-is so vivid that to this day "Al-Sayyid" is shorthand in the Arab world for a ridiculously dominating man. And just as Mahfouz exposes the excesses of a previous generation, he deals with the agonies of his own. The youngest son of the family, Kamal, is the writer's most autobiographical character. We see him in a browbeaten child in the first book, stifled by the fear of his father's disapproval. By the end of the trilogy, he is a teacher haunted by an unrequited love. He is educated and free, yet unhappy-an atheist and an alienated intellectual who feels that his life has not amounted to much. Mahfouz later told Al-Ghitani that "Kamal's crisis was my crisis, and his suffering was my suffering."24

Kamal's nephews, the youngest generation in the trilogy, are far more confident about what needs to be done in the country. One of them is a communist, in an equal marriage with a female comrade. The other is a member of the Muslim Brotherhood. Through them, anticipate Mahfouz the two strongest strands of political opposition that the country will witness in the decades to come. He also anticipates the way that the state will meet this opposition. The trilogy's last novel, Sugar Street, concludes with both young men- "the one who worships God and the one who does not" -under arrest in the last days of World War II. "You must love the government first and foremost if you wish your life to be free of problems," Kamal observes.25

The Cairo Trilogy catches the startling pace and often changes in the world of consumption in the world in the mid-20th century, particularly in those countries undergoing decolonization. Children of the Alley, Mahfouz's next work, is a bit different from that of reality.26

The novel begins with the expulsion of one of their father's enchanted house and garden. (As usual, the bad brother is much more interesting than the good one.) Their multiplying descendants live in misery alongside the gated palace of their ancestor, Gabalawi, who dwells unseen behind the walls. He is beloved, awesome, terrifying, and inscrutable. His estate is monopolized by a greedy overseer; thugs rule and rob the people in his name. The inhabitants of the novel are following different leaders who, over the years, reclaim their inheritance. These leaders evoke Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad (a final, fourth leader represents modern science). Even if the uprisings are successful and establish a new, more just diet, by the beginning of the next chapter it is: the overseer, the thugs, the misery.27

Mahfouz has described the novel as "metaphysical." It moves through cycles of revelation and rebellion, collapse and oppression. "Why is forgetfulness the plague of our alley?" The narrator asks. And the story has a mythical quality to it, its characters are human. The most important moments of their lives-their loves, grievances, and deaths-are etched in sharp relief. Mahfouz writes: "A profound and absolute sadness seized him, eclipsing even his fears. It's going to be in the dark. "Another man, who is deeply in love with his wife, approaches her on their wedding night. "She seemed stately, soft-skinned and radiantly beautiful; the walls gazed down on her with a pearly light. "28

The novel was serialized in Al Ahram in 1959. It attracted the attention of the country's highest religious authority, Al Azhar, which condemned it as blasphemous. Al Ahram'S editor, Mohamed Hbadanein Heikal, to Nbader confidant, saw the serialization through, but thereafter Mahfouz never attempted to publish the novel in Egypt. After he won the Nobel Prize, he was denounced by radical Islamists, who in the 1990s were violently challenging the state and targeting members of the intelligentsia.29

The book raised a question that continues to hang over Arab and Muslim countries: What is the relationship between religion and politics? in Children of the Alley, religion is both a rallying cry against injustice and a cover for it. Mahfouz's impiety consisted of every single faith-he does not only discuss Islam-is used to mask and further earthly interests. The novel is also particularly good at capturing a group of people in the world of cruelty, fear, anger, or bravery. For example, when a crowd impulsively intercedes between a gangster and the young man he is intent on beating, their courage is inversely proportional to their chance of being identified:30

"Our protector, the crown on our head," said a man in the front row of the crowd, "we have come to your forgiveness for this good man."31

"You are our protector and we obey you," shouted a man from the middle of the demonstration, emboldened by the size of the crowd and its location in it. "But what has Rifaa done?32

"Rifaa is innocent, and woe to anyone who harms him!" Shouted to a third man, to the rear of the crowd, rebadured that he was invisible to the gangster's eyes.33

Yet while Mahfouz's narrator observes the people, they can not, his sympathy for them is not undercut by it-in fact, it has almost the opposite effect.34

This clear-eyed but forgiving vision can be found, at times, in Mahfouz's columns as well. To a young woman angry about the hypocrisy and mediocrity she sees everywhere, Mahfouz writes: "Miss, I hope you're abandoning some of your idealism-and not a small part of it. The society that you look at iniquity, war, poverty, and crises. Do not expect a picture of cleanliness, elegance, and good health. "Mahfouz, Mahfouz, Mahfouz, Ph.D. writes: "What I want, sir, is action and conduct, not the quotation of sublime verses which we do not act in accordance with."35

Yet these glimpses of his personality are relatively rare. Most of the time, Mahfouz is obvious, simplistic, even callous. Sometimes he betrays his own liberal and democratic principles. In a column about corruption, he writes: "Our need for political parties and pulpits may be less-at this time at least for our police officers, informers, prisons and gallows."36

Mahfouz preserves what Rasheed El-Enany calls for "quiet justice." He has nothing to say about the bread riots of 1977 (a near-uprising against the austerity of the International Monetary Fund) ), and he seems to be taking over the claims of political pluralism and liberalization of the press made by the government of Anwar Sadat.37

Mahfouz did eventually have his say on most of Egypt's revolutions and regimes-but in his own time, and on his own terms (and sometimes from the safe distance afforded by a president's death). In his book of reminiscences, Al-Ghitani describes Mahfouz's habit of ignoring questions that he did not wish to answer, or of pausing so long as the conversation moved on-only to start the everyone with a comment about the matter after all. There was a similarity in his reactions to the many momentous political changes he lived through, and it was only in his fiction that he dealt with his preoccupations and observations into something rich, original, and complex. In the novels he wrote in the 1960s-Adrift on the Nile, Tea Thief and the Dogs, Miramar-Mahfouz captured the disillusionment and cynicism that eventually followed the 1952 revolution, as the shortcomings and authoritarian impulses of Nbader became apparent. The books all turn on a murder, and this black is part of their jaded atmosphere. The 1960s are in their infancy, and they are not so far in their lives, and their actions are second-guess their principles, and even their own reality. In their obvious but coded critique of the Nbader regime, these stories are quite daring.38

After Egypt's defeat by Israel in the 1967 war and Nbader's death in 1970, Mahfouz wrote more openly about the shortcomings of the previous regime. His 1974 novel Karnak Coffee was inspired by Mahfouz 's own experience of being spied on in cafes. "We were all living in an unseen powers-spies hovering in the air we breathed, shadows in broad daylight," says its narrator. The students in the novel who meet in their titular coffee have no subversive intent but are not forced imprisoned, tortured, and forced to inform one another; they are children of the 1952 revolution, whose faith in it has been betrayed and broken. By the time one character emerges from his third stint in prison, only to learn from the Arab countries' shattering loss to Israel, he is convinced that "we had been living through the biggest in our entire lives."39

Mahfouz, like all Egyptians, was deeply shocked by the unexpected outcome of the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. But he came to argue that if Israel did not have the ability to beat Israel militarily, it should pursue a political settlement. He supported Sadat's trip to Jerusalem and the 1979 Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty. Afterward, there were calls to the Arab world.40

Sadat's time in power was one of the most volatile eras in Egyptian history. There was great opposition to his peace treaty with Israel in the liberalization of the economy and the unbridled corruption that followed. But one would hardly know any of this from Mahfouz's columns. When Mahfouz did paint a scathing portrait of the Sadat era, it was again in a novel, The Day Leader Was Killed, which he published after Sadat's murder in 1981. By contrast, the piece he wrote for the newspaper six days after Sadat died, "Eras and Leaders," is bizarrely detached. He describes the achievements of Nbader, Sadat, and the new president, Hosni Mubarak. in "an ethical revolution to inspire new hope."41

The column is the performance of a short scribe making the best he can of the new ruler. Mahfouz may have been self-interested, but he was also somewhat sincere. As was true of the vast majority of Egyptian intellectuals, Mahfouz's nationalism meant that he could never have set himself up against the state of the world. In fact, when he did so, because of his loyalty and his personal identification with Egypt's interests.42

During the Mubarak years, Mahfouz's engagement with politics in his fiction became increasingly popular. The already aged writer looked at the past, or inward. "The narrator of" Children of the Alley us. "It was my job to write the petitions and complaints of the oppressed and needy …. I am privy to so many of the people's secrets and sorrows that I have become a sad and brokenhearted man. "Mahfouz himself was far from gloomy, but he ounce told Al-Ghitani that as far back as Egyptians can remember, they had been disappointed .43

Moments of hope-the revolutions of 1919 and 1952-were invariably followed by concessions, failures, and repression: "The moment we breathe we find there is someone crouching over us, snatching our breath and ruining our lives." his writing had been "a struggle against futility" -a struggle that he never gave up.44

[ad_2]

Source link