[ad_1]

It would become known as the Great War, or the “war to end all wars”. Four years of bitter conflict from August 1914 to November 1918 which spread to involve more than 80% of the world, causing 37m casualties, military and civilian, and 16m deaths.

For the past four years, we’ve been examining the major issues and events of World War I: from its outbreak in the summer of 1914, through its major battles, such as the Somme in 1916, to its conclusion on November 11, 1918. We’ve asked a large array of academic experts to comment on everything from the geopolitics, tactics and technology to the war’s legacy. Here are some of the things we have learned:

What happens in the Balkans…

Wikimedia Commons

All the schoolbooks tell us that it was a young Bosnian serb, Gavril Princip, who badbadinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand to start the clock ticking towards conflict. But most of the great powers, particularly Germany and Austria-Hungary, had been planning for a war in Europe for some time and Princip’s bullet gave them the chance they were looking for.

But if the politicians were gung-ho (aren’t they always?) ordinary folk weren’t so bullish. It took a concerted campaign of jingoism to get the drums beating on the Home Front.

Mud and blood: the trenches

nationallibrarynz_commons

The enduring picture of World War I is of muddy trenches, barbed wire and bomb craters. Lice, trench foot and myriad other diseases (flu, malaria, typhoid) took a heavy toll on troops on both sides. And the poor diet was also hard on their teeth. Nor was this confined to the ranks: the British military commander, General Douglas Haig, developed such excruciating toothache at the Battle of Aisne in the summer of 1914 that a dentist had to be sent for from Paris.

Boredom was also a problem for many soldiers awaiting the next big push. Troops had various ways of relieving this, including their own satirical newspaper, The Wipers Times.

Battles could often last for months and achieve little. Perhaps the most famous, certainly for the British, was the Somme – which lasted 141 days and cost 300,000 lives on both sides. The battle changed the way the British approached the war – from then on, production of tanks and aircraft in particular soared as Allied tacticians sought to break the trench-based deadlock.

War at sea and in the air

thirtyfootscrew

It was “total war” which, for the first time, was waged on land, sea and in the air. It has been estimated that 14,000 Allied pilots lost their lives – more than half of them in training – but then the first manned powered flight had taken place just 11 years before the war broke out. Surprisingly, however, aerial combat has remained fairly constant since.

But what of the war at sea? After the Battle of Jutland, which pitched the British Grand Fleet against Imperial Germany’s High Seas Fleet, Britannia largely ruled the waves. Winston Churchill subsequently said that the British sea commander, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, was the only man on either side “who could have lost the war in an afternoon”. Happily for the British, he didn’t.

Women at war

www.gwpda.org/photos

Women also played an enormous and vital role: whether on the home front growing and cooking the food or working in the factories that powered Britain’s industrial effort, or as nurses, serving in dangerous conditions. Women volunteers were at the front within weeks of the conflict beginning and served with bravery and distinction. It’s generally thought that the social changes wrought by the Great War saw women get the vote in Britain far earlier than they otherwise might have.

1918: peace at last

US National Archives

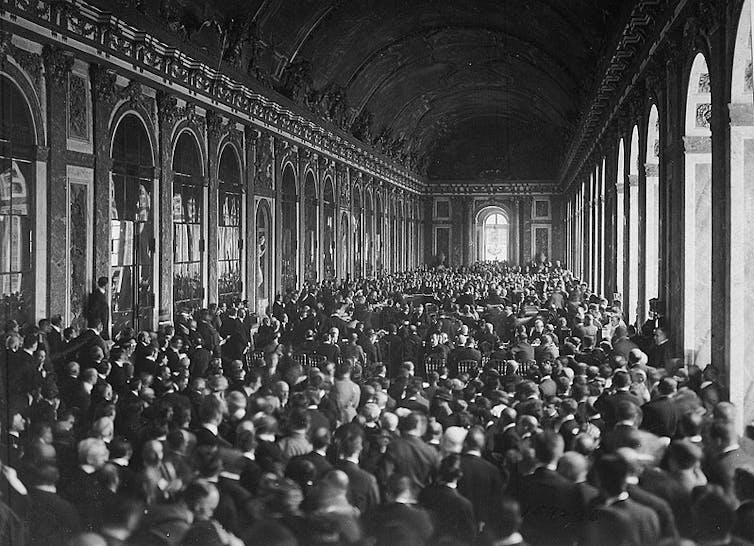

Sunday November 11, 2018 will be a chance for the world to reflect. To start with, to call it the “war to end all wars” proved tragically optimistic: within a single generation the world was plunged back into an even more destructive conflict, the seeds of which were sown in the harsh peace treaty imposed on Germany and her allies at Versailles.

The legacy

Asked in the mid-1930s to reflect on the medical advances made during World War I, an unnamed Austrian medic said:

Nobody won the last war but the medical services. The increase in knowledge was the sole determinable gain for mankind in a devastating catastrophe.

But it’s never too late to learn. Anyone who still believes that war is the solution to anything should read the words of the most famous war poet of them all, Wilfred Owen – whose life was cut short and whose talent was extinguished at the desperately young age of 25, just seven days before the guns fell silent:

My subject is War, and the pity of War.

The Poetry is in the pity.

Yet these elegies are to this generation in no sense consolatory. They may be to the next. All a poet can do today is warn.

While you are here…

Please listen to our podcast, in which we talk to academic experts about how the Armistice came about, three of the great World War I poets, and what life was like for the brave conscientious objectors who refused to take up arms.

Source link