[ad_1]

TBowing during a nine-minute encore, Terence Blanchard could see that this was no ordinary night at the opera. The 4,000 spectators of the Metropolitan Opera in New York are striking for their racial diversity.

“There were so many proud faces,” recalls the songwriter from last week’s premiere. “Obviously he was pointed at me, but he was much taller than me. Seeing yourself on stage, seeing people they knew, seeing the culture on the Met stage made people cry.

The Blanchard Fire in My Bones was the first staged job in the home since March 2020, when the coronavirus pandemic forced a city-wide shutdown. More importantly, and surprisingly, it was the first by a black composer in the 138-year history of the Met.

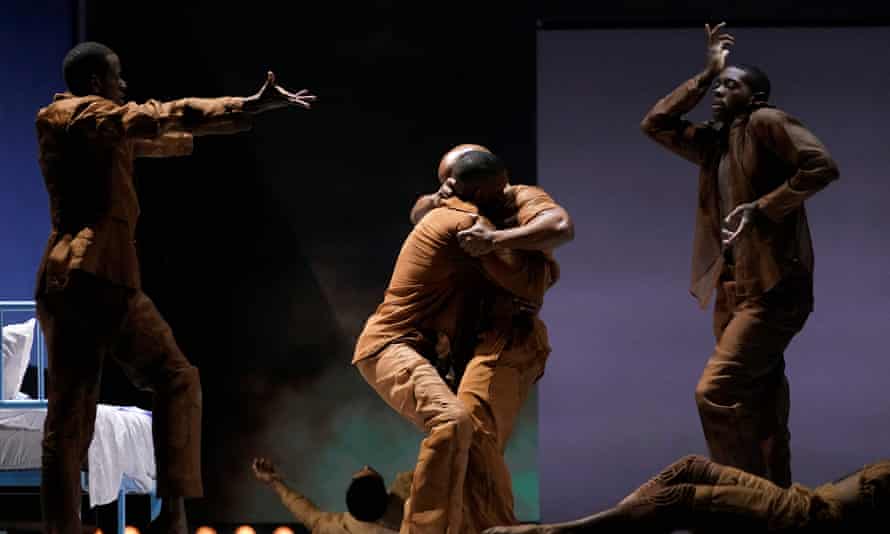

The opera, which has an all-black cast, is based on a 2014 memoir by New York Times columnist Charles Blow, a heartbreaking story of child abuse in isolated northern Louisiana from the 1970s. It has premiered in 2019 at the Opera Theater in Saint Louis, Missouri.

When the Met first called to stage the work, Blanchard, 59, a jazz trumpeter, conductor and composer best known for composing Spike Lee films, had no idea that ‘he would go down in history as the first African-American to have an opera performed there.

“I had no idea and all of a sudden this reporter asked me this question and I was like, ‘Ah, come on, you’re kidding me, aren’t you?'”, he said over the phone. “That was my reaction: there’s no way I’ll be the first! I can’t be, no, no. First it’s New York, you know what I’m saying? And then when that was confirmed, I was saddened. It’s an incredible honor to experience this, but the sad part is that I know I am not the first to qualify.

Blanchard cites Scott Joplin’s work as an example. Another came to him this summer when he heard a performance of Highway 1, a one-act opera by black composer William Grant Still first premiered in 1963, at the Opera Theater in St Louis.

“You sit there and you’re like, ‘Wow, if it weren’t for the color of their skin, this music would’ve been played at the Met,’ because when I heard Highway One, I thought it was amazing, beautiful. , gorgeous, and I was literally like, “What’s wrong with that?” Tell me what was wrong with this room. Tell me what’s wrong with this music.

“I’ve always been convinced that I’m a very idealistic person at one point, but my thought was, if you’re really, really really about the arts, tell me what’s wrong with this piece and why it is. couldn’t be at the Met. “

The Met has traditionally promoted the canon of dead white European composers; living artists had better luck at the New York City Opera, which produced Still’s Troubled Island in 1949. Blanchard says he can only guess why the Met, in theory an open-minded institution in a liberal and diverse New York , continued to refuse black composers for so long.

It parallels the reaction to the murder last year of George Floyd, an African American in Minneapolis, by white policeman Derek Chauvin, who rested his knee against Floyd’s neck for nine and a half minutes. The murder sparked nationwide Black Lives Matter protests. Chauvin was sentenced to 22 and a half years in prison.

Blanchard says: “I guess that’s the type of racism that people don’t even realize they’re engaged in. For example, when George Floyd was killed it was amazing the response I got from people I have known all my life who are well meaning people. It was the first time they had seen real evidence of what we had been crying against in decades.

“People would call me and say, ‘Are you okay? I didn’t know what they were talking about. Like, ‘What happened? Has something happened to my wife that no one has told me about yet? They’re like, ‘No, no, we just saw the George Floyd thing.’ And I’m like ‘Wow, alright.’ It blew me away because it took that to really wake them up because I’m not saying they were overtly racist.

“I’m just saying he didn’t check in with them like he checked in with us because they never saw him, and when they saw him, there was always these explanations. where “you have to see what happened before the video” – all of those excuses.

“But with that, there was no excuse: the man’s knee was on his neck for an extended period once he was already under control and you can’t explain why he did what he did. did aside from the fact that he just hated Black people. So I think that woke people up and made people realize that you need some responsibility and you need to be held accountable to all these institutions. ”

It’s a calculation that has spread to art galleries, museums and theaters in New York City, where a record-breaking seven works by black playwrights opens this fall and where industry leaders have agreed to a “New Deal for Broadway” to seek diversity, equity and inclusion.

But opera carries particular connotations of class and racial elitism. Peter Geib, Managing Director of the Met since 2006, publicly acknowledged the impact of the Black Lives Matter movement and why it was important for the institution to respond.

Earlier this year, the Met hired Marcia Sells as its first head of diversity and enlisted three composers of color – Valerie Coleman, Jessie Montgomery, and Joel Thompson – for its commissioning program. Black composer Anthony Davis’s opera X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X will premiere at the Met in 2023.

Blanchard adds: “I will give Peter Gelb all the congratulations in the world for wanting to right a wrong. What’s cool won’t be just me. I am really happy that I am not a token, that I am not unique.

Like Blow, Blanchard is originally from Louisiana and owes his love of opera to his father, who in turn was trained by Osceola Blanchet, a high school chemistry teacher and church organist in New Orleans. “My father and a few other African-American men would rehearse every Wednesday evening at Mr. Blanchet’s and sometimes I would go there. We talk about this community, to have been raised by a village: it was really my experience.

“One day I became moved as I sat down browsing the names in my head of all the people who have had a positive influence on me in the arts. They were all African American and none of them made a name for themselves. None of them were ever acclaimed, but they really loved the arts.

Blanchard has won five Grammy Awards for his jazz records. He has written scores for over 40 films including 17 of Lee, winning Oscar nominations for BlacKkKlansman and Da 5 Bloods. Lee attended the first two performances of Fire Shut Up in My Bones and plans to return for the closing night.

Blanchard credits the world of cinema with helping him understand how to tell stories and the world of jazz helped him develop a language – harmonic, rhythmic or melodic – to communicate them (he is not a modern minimalist). His first opera, Champion, in 2013, was about the life of locked up gay boxer Emile Griffith.

Classical music always has white gods by whom all tend to be judged. Last year, when plans were announced for a film about 18th century color composer Joseph Boulogne, the headlines couldn’t help but dub him the “black Mozart.” The soubriquet was condemned as humiliating in a New York Times column by composer Marcos Balter.

What would Blanchard think of such a description? “I understand it but I don’t want to be a black composer; I want to be a composer. I understand why it is necessary to say this because of its historical nature and importance. I understand. But there are things inherent in this statement that I think people don’t realize.

“A reporter asked me if I thought white people would come to see this opera? I said, your question just insinuates that black people are not going to see the white opera. The absurdity of some of the questions behind this stuff is just crazy to me because people don’t realize what they’re saying in their attempt to be open. For me, this is such a stupid idea.

“Why don’t people come and see this? Because there are blacks on stage? Well that’s a very selfish thing on their part because they expect people to see and experience their culture on stage. It does not make sense and it does not really correspond to the very notion of people who are curious or eager to learn. People always say, “Oh man, the arts are about expanding your consciousness.” OK, well, here we go.

Fire Shut Up in My Bones, with a libretto by Kasi Lemmons, opened on September 27 to ecstatic reviews and will visit the Lyric Opera in Chicago in March and the Los Angeles Opera in an upcoming season. National Public Radio said: “It was astounding to witness this jolt of proud Kinetic Blackness on the Metropolitan Opera stage.” The Observer website suggested, “Shortlisted for Best American Opera of the 21st Century. “

Blanchard sums up this first night in one word: humility. “Some of my toughest friends came up to me, ‘Dude, you made me cry four times.’ But I think those tears were tears over what it meant, what is happening in the country, how it can change things. It’s a testament to the desire that we’ve had for generations just to be equal, man, just to be able to do what everyone else does and be seen.“

[ad_2]

Source link