[ad_1]

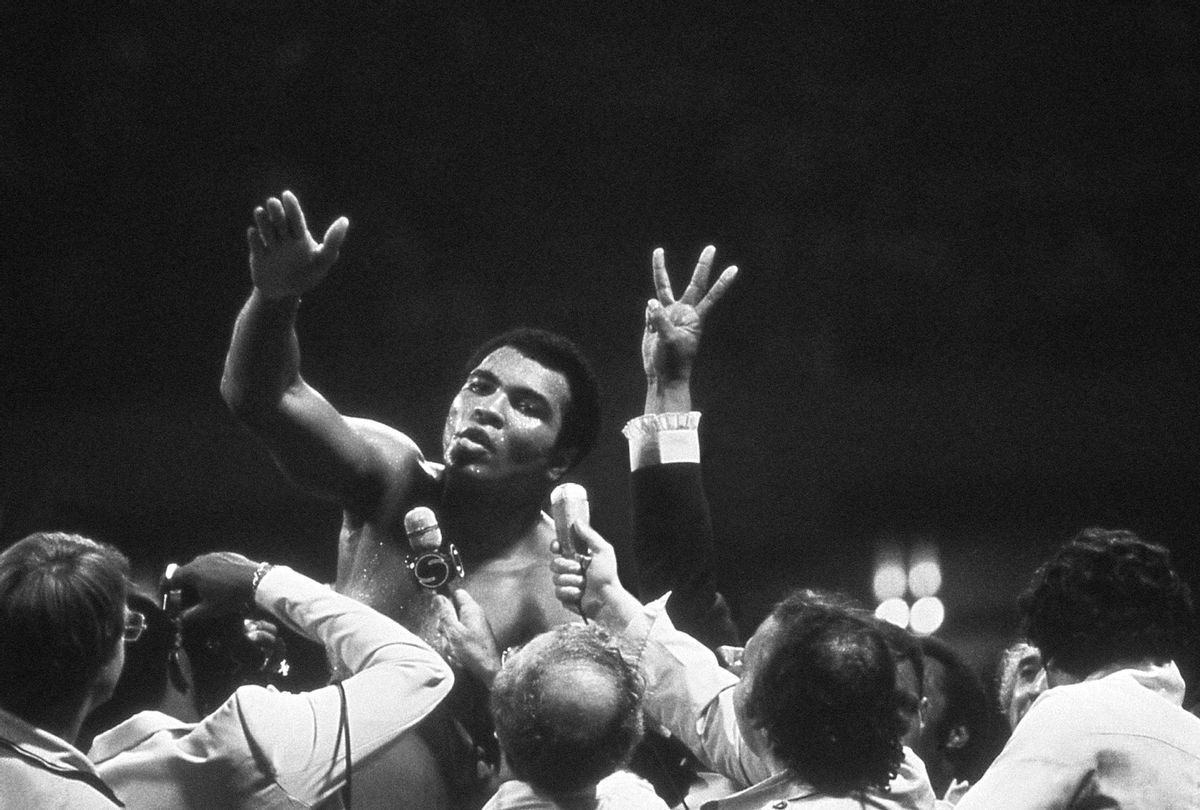

Watching “Muhammad Ali” allows a person to appreciate the serious duty that Ken Burns has undertaken to do. This is not said of a nostalgic or emotional location, although the four-part documentary is designed to elicit a range of feelings about the boxer, with some of them contradictory.

Sentiments aside, what is striking is how Burns and coworkers Sarah Burns and David McMahon have taken up a biography that has been reviewed and interpreted time and time again, and still manages to make their version a must-see.

“Muhammad Ali” is a rare piece by Burns made with an awareness of the broad fandom of its subject matter and the fact that millions of viewers have grown up watching a version of Ali on television in one form or another. Burns is no stranger to browsing recent viewer history or profiling individual athletes.

That said, examining the enduring significance of Jackie Robinson, as the three filmmakers previously did, or Jack Johnson, the subject of Burns in 2005, presents a different challenge than analyzing the life of The Greatest. It takes respect, care, and sobriety, but less of the dry seriousness that permeates Burns’ other historical treatments. With that in mind, “Muhammad Ali” is more than called a heavyweight, but he floats as well as he stings.

Want a daily rundown of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

A life and career defined by triumphs, setbacks and moral contradictions played out on camera make Ali a popular subject among filmmakers and television producers. Decades of scripted and unscripted releases have ensured a permanent place in the collective consciousness. Some of the best include Leon Gast’s 1996 Oscar-winning documentary “When We Were Kings” and “What’s My Name: Muhammad Ali”, Antoine Fuqua’s excellent 2019 HBO documentary. Even recently, Netflix kicked off “Blood Brothers,” a tight shot on the friendship the athlete shared with Malcolm X.

Fictional performances include Regina King’s 2020 Oscar nominee “A Night in Miami” and the famous “Ali,” the 20-year-old feature film starring Will Smith. The list of sports documentaries, reports and talk show interviews would be too long to include here, although his spur of the moment poetry is worth watching.

All this to say that Burns doesn’t reveal much in “Muhammad Ali” that you don’t already know, whether it’s because you’ve watched these and other efforts, or because for a very long time Ali seemed to appear. everywhere – whether he sells watches or his own legend through a 1970s Saturday morning cartoon.

People who have never seen him fight or seen his television guest appearances know something about the man even if that knowledge doesn’t extend far beyond his catchphrases. But let you know all or next to nothing about Boxer Burns’ Over Seven Hour Treatment contains enough magic to hold your attention and more.

“Muhammad Ali” rumbles with all of Burns’ usual signings, like the enlistment of Keith David to tell again, as he did for “Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson” and Jackie Robinson. A few nods to culture – an excerpt from a hip-hop track here, a bar or two of “Lemonade” there – modulate and modernize its tone. (Never let it be said that the filmmaker does not know the rhythms of his subjects or their audience.)

But the soundtrack is just a blossoming adding a motto to the standard chronological construction of Ali’s life, starting in “Round One: The Greatest” with his early youth in Louisville, Ky., And his initiation into music. boxing, climbing the ranks of the amateur circuit before winning a gold medal at the 1960 Summer Olympics. These scenes give us our first glimpses of photographs and footage that have not appeared anywhere else. One of the ways Burns sets his work apart is by making the most of a level of archive access that others don’t.

Another is more vital and central to arguing for the essentiality of “Muhammad Ali”, which is the emphasis the directors place on placing the subject firmly in the context of the time being lived.

With Ali, that means explaining the popularity of boxing as a sport, and it also requires, for example, exploring the reasons for his conscientious objection to being drafted to fight in the Vietnam War. And that requires a concise exposition of the Nation of Islam, what it meant to black America, and how white America feared it.

This is not just about defining religion or establishing its main players, but explaining the racial and social implications of the white sports establishment’s refusal to respect Ali’s name change from Cassius Clay. .

Burns has spent a career examining American history through the lens of race and racism in America, and Ali draws a line from the civil rights era to the present day. Our nation claims Ali as a hero now, but in his heyday the establishment couldn’t stand him. He posed as the champion of blacks all over the world. Unsurprisingly, the World Boxing Association stripped Ali of his heavyweight title after announcing his conversion to Islam, and the United States government threatened him with five years in prison. Meanwhile, as he has repeatedly pointed out, white conscientious objectors were sentenced to two years on average, even if they broke the law.

Ali’s insistence on being called by his new name becomes central to building the myth of Ali as elite athlete and one-symbol champion – hence the title of the second episode, “Round Two: What’s My Name? “

But “Muhammad Ali” hits harder in the long stretches where the filmmakers allow the fight sequences to unfold with the lightest editing, and sound amplification allowing us to hear Ali taunt his rivals and deliver his punches. It brings ferocity to life like nothing else.

Nowhere does this play out more powerfully than in “Round Three: The Rivalry,” a detailed analysis of the enduring enmity between Ali and Joe Frazier, the first boxer to beat him.

To have New Yorker editor David Remnick set the scene and retired fighter Michael Bentt explain where the fury of each punch comes from is staggering. Seeing grudge play out piecemeal helps audiences understand the difference between two men trying to win a match and enemies desperate to annihilate each other. You can almost feel the humidity and tension in the room.

Others, like Walter Mosley and Ali’s daughter Rasheda and her brother Rahman, give their personal take on the weight of Ali’s legacy and how it resonates in their lives and in the culture in general even now.

Burns’ obvious affection and esteem for the champion dominates all four segments, but that doesn’t stop pundits or filmmakers from pointing out the many times this widely respected civil rights icon has used demeaning racist tropes to promote. his skills and demoralize his opponents. , especially Frazier, who never gave up on their feud. Even that heroic “what’s my name?” bout included several instances of Ali calling his opponent Ernie Terrell an Uncle Tom.

Yet when his record and reputation were not at stake, Ali was known for his generosity. Rasheda Ali says her father gives money to strangers who ask for help to make them feel special.

“In Ali’s presence, you always felt that he cared about him,” says poet Nikki Giovanni. “That moment when he was with you, there was no one else in the world. And I’m not sure that’s true for a lot of people.”

Again, much of this territory has yet to be discovered. But “Muhammad Ali” demonstrates that in-depth examinations of a personal history can be as substantial as work that delves into specific parts of it. The best Ali documentaries are detailed and meticulously drawn.

This four-night trip does these things with a wider sweep, extreme care, and a mind that is not only fair and clear-headed, but in an undeniably loving way, especially when it comes to the declining health of the former champion in the years leading up to his death. in 2016. No matter what you know about Ali, the spell remains, as the title of the final “round” suggests. You will be happy to fall for it.

“Muhammad Ali” airs on four consecutive nights: Sunday to Wednesday September 19-22 at 8 p.m. on PBS.

[ad_2]

Source link