[ad_1]

Last August I switched my entire digital life from an Apple MacBook Pro 15 to a first generation iPad Pro 12.9–and I never looked back.

A few days ago, Apple CEO Tim Cook took the stage of the Howard Gilman Opera House in Brooklyn to announce new iPad Pros and declare that Apple’s tablet was actually the best-selling computer ever. Many people laughed at that idea. I didn’t. The iPad has been my only computer for three months now, and I couldn’t be happier.

I’m able to do everything I used to do with my MacBook on my 12.9-inch iPad Pro. I’m writing this article on iA Writer, my favorite word processor. I use Google Docs for general collaborative writing and WriterDuet for TV scripts with my partner. I draw concept art and illustrations in ProCreate, retouch and create images on Affinity Photo, and assemble draft sizzle reels on iMovie. I craft pitches on Keynote, track my work on MeisterTask and AirTable, collaborate with clients on Slack and Skype, and chat with my partners on Google Chat. I navigate in Chrome. I read books in Apple Books, browse news in Feedly and Reddit, and enjoy old Kirby and Steranko comics on Marvel Unlimited. I Netflix, HBOGo, Hangout, Facetime, Message, Gmail, and do all my banking in different dedicated apps. And I just finished playing Thimbleweed Park (which is an awesome game, by the way. Go get it).

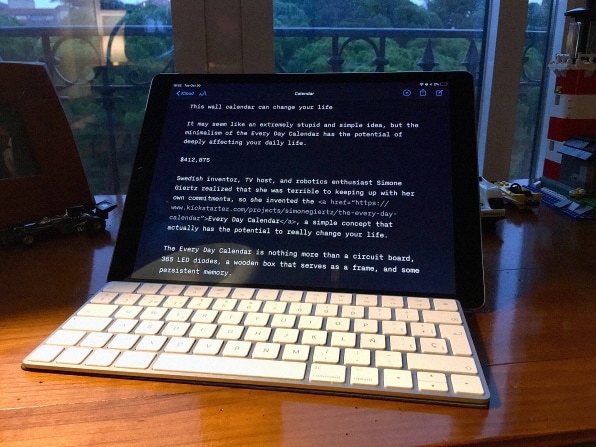

To be clear, the iPad Pro isn’t perfect. The Smart Keyboard for the iPad Pro sucks–it’s too flat, and doesn’t have enough key motion–so I got myself an Apple Magic Keyboard 2. I also got Studio Neat’s Canopy, a keyboard case and iPad stand combo that turns the iPad into the perfect workstation. When I need to write, I can work in landscape or portrait mode, which helps me concentrate on that single task. And when I don’t need to write, I just use the iPad on its own, like a paper notebook. (I also have an Acme Made iPad sleeve so I don’t even need to use a bag.)

If you are thinking that an iPad with a keyboard is a laptop, you are wrong. The iPad is better than a laptop. Better than any other computer I’ve used before. And I’ve been looking for the perfect computer for a long time.

The quest for the perfect computer

I started to use computers with an Apple II clone at home, a Commodore 64 at school, and ZX Spectrums at different friends’ homes. Back then, I programmed in Basic and loaded games on tapes. Then I went through a bunch of PCs from an IBM XT all the way up to a DEC Pentium. In my college years I bought myself an Apple PowerMac 8100. After that, all my computers have been Macs until my very last one, my trusty Macbook Pro 15 Retina, the one I abandoned this summer for the iPad Pro.

Through those four decades I saw computing evolve from a green phosphor prompt line to the most advanced form of the desktop metaphor, macOS. I enjoyed tinkering with all those PCs and Macs, and I was an expert user by most measures. But through those years, taking care of my data became a chore.

As computing power and storage space skyrocketed, the amount of time I spent managing my digital life increased proportionally. Project files piled up on folders all over my hard drive. My personal photos were distributed across 100 places. I had to decide how to organize stuff. And as things got more and more complex, the user experience got more complicated.

The desktop metaphor that Apple had pioneered became only marginally better than the command line. The amount of “life hacks” I had to do to manage my files and keep my eyes from twitching every time I looked at my desktop and folders was just too much. Using database-like programs to organize images and videos helped, but overall the desktop metaphor was not made for all this practically unlimited computing and storage power. You can’t just organize a hundred billion files on a virtual desk and file cabinet.

Jef Raskin and the information appliance

Something happened along this road. In 2010, the iPad became a reality.

The original iPad reintroduced the concept of the information appliance, an idea pioneered to its full potential by Jef Raskin. Raskin, who was a human interface expert and led the Macintosh project until Steve Jobs took it over, thought that the only way to harness the power of computing in a rational way was a concept called the “information appliance.”

For Raskin, computers were supposed to be our servants, but instead they were oppressing us with their prompt lines and arcane commands. Only a handful of tech popes and hobbyists could master them. Raskin advocated for their elimination. Instead, he said, we needed machines with one single purpose, just like a toaster makes toast and an immersion blender turns solids into purées and sauces.

These gadgets needed to be so easy to use that anyone would be able to instantly grab one and start using it, without any training: The information appliance, he said, would have the right number of buttons in the right position with the right software to do a specific set of tasks. Always networked, these appliances would be so easy to use that they would become invisible to users, just part of their daily life.

Raskin eventually realized that having one gadget for each possible task wasn’t logistically possible. No one wants to walk around with 200 gadgets each. But he thought that the Macintosh could fulfill the promise of the information appliance thanks to its graphical user interface, with programs that could change on-screen and perform specialized tasks better and more easily than the command line computers.

The Mac became a giant leap in computing, but it was still one step removed from his dream. At first, it was extremely simple. It was a modal computer, which each program running on the full screen, launched from diskettes. Your mind could concentrate on one task at a time. People instantly got it.

Then, the Mac first and Windows PCs after it, became more complicated. Multitasking killed modal computing. And it brought complexity. At first, not too much. Then, as processors and hard drives evolved, lots of it. These brought cluttered desktops and folders. After a few years, it all became a big clusterfuck. So big that Tim Cook recently said that he couldn’t live without macOS Mojave’s Stacks, a software that cleans the desktop by making little groups of files organized by type. But Mojave’s stacks are actually just a band-aid to clean desktop clutter and leave you with a bunch of unorganized documents piles. It treats the symptom but it doesn’t solve the problem.

It wasn’t until Raskin saw touchscreens that he realized what the future actually was: A single screen that could morph into an infinite number of “soft” devices with the right buttons in the right places at your fingertips. A GPS, a camera, a calendar, a book reader, a drawing pad, a sound recorder, a guitar tuner, an image compositor. You could make it do anything, transforming it into different information appliances on the fly.

Ultimately, Raskin didn’t make it happen. It was Jobs who brought this idea to the world with the iPhone. And people instantly got it. People who were confused by Macs and Windows and couldn’t stand computers embraced these little screens that magically transformed into a myriad of useful dedicated “devices,” each with their own function. And there were no folders or files.

When the iPhone came out, Jobs called Alan Kay–who invented the Dynabook, the very idea of the tablet computer–and asked what he thought of it. Kay said that it was pretty great but that he should make it “five inches by eight inches” to truly rule the world.

Jobs did what Kay said and released the iPad in 2010 (in fact, Apple was working on the iPad before it started work on the iPhone). Kay was sort of mistaken, as the iPhone was the device that transformed society. But he was sort of right too, as Tim Cook said when he announced the new iPad Pro: “the iPad is the world’s best selling computer.” He’s right about that: While the iPhone is a tiny device that is great to consume media, play games, and communicate, it’s not a computer. The iPad, on the other hand, allows you to create just like a computer does, and then some, thanks to its Pencil.

The future is finally here

Which brings me back to my original question: Why is the iPad Pro the best computing experience I’ve ever had?

Because the iPad Pro gets the best of the classic computer–its raw power and capacity to create content–but escapes the complications of the desktop metaphor. The apps take over the screen to transform it into dedicated devices specifically tailored to do the specific tasks I need to do, focusing exclusively on them, without a million open windows.

And instead of having to worry about organizing my work in folders and files, my word processor, painting app, or photo apps take care of my files on their own. Everything is contained within its own space. I don’t worry about files. And when I need to find something, I just use the search box.

That’s why I love the user experience. From the lack of clutter to the modal nature of apps, it feels like it was designed for concentration. I’m more efficient on the iPad.

Working on an iPad has also elevated my digital well-being: Without having to worry about how my computer works or where my stuff is, I have jettisoned the parts of computing that stressed me out and made me waste time.

I was a huge fan of the original iPad; I called it the future of computing in 2010. But it was too limited to switch my life to it: it wasn’t powerful enough and didn’t have the apps I needed. The second and third versions fell short too. It wasn’t until the iPad Pro and iOS 11 came out that the iPad became a viable alternative to “real” computers.

iOS 11 introduced the right amount of multitasking features–split screen, drag and drop, and gestures to summon or dismiss apps–that are needed to work faster in some specific cases. For example, while working on a pitch deck in Keynote, sometimes I figure out that I don’t have a number of images I need. I can quickly summon Chrome by dragging its icon from the iPad’s dock to one side of the screen. The display divides neatly into two columns. I search for materials in Chrome and drag and drop with my finger into Keynote. Once I’m done, I just dismiss the browser by swiping Chrome out to the side of the display and boom, I’m back to fully concentrating on the pitch.

The new iPad furthers the case for tablets to be full desktop or laptop replacements. The new hardware design is gorgeous, with rounded corners, small bezels, and square edges. More importantly, it is a true processing powerhouse. Apple claims that it can match the graphics performance of the Xbox One S–which is Microsoft’s top game console, a monster capable of moving a gazillion 3D polygons at UltraHD 4K resolution. That’s incredible for a product that is 94% smaller than that game console–and runs on batteries. During its introduction, Apple also said that the new iPad Pro is faster than 92% of all laptops sold last month.

All while keeping the simplicity of the “information appliance” and modal computing. The new machine will run full Photoshop as fast as most laptops and desktops. And the new Apple Pencil–with its magnetic latch, gesture controls, and wireless charging–is icing on the cake for those who draw for a living, or for anyone who needs to annotate documents or create presentations.

So yes, iPad is the future. And for me, as cliché as it sounds, the future is now.

[ad_2]

Source link