[ad_1]

Tired of corruption and Trump, voters accept the leftist and unconventional Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Excellent chronicle.

John Lee Anderson, The New Yorker.

Regeneration July 1, 2018 . The first time that Andrés Manuel López Obrador presented himself as a presidential candidate for Mexico in 2006, he inspired so much devotion among his supporters that sometimes they put stamps in their pockets, with messages of their own. Hope for their families. In an age defined by globalism, he was a defender of the working class – and also a critic of the PRI, the party that ruthlessly dominated national politics for much of the last century. During the election, the fervor of their constituents was obviously not enough; Lost by a small margin. The second time that he competed, in 2012, the enthusiasm was the same, and the result too. Now, however, Mexico is in crisis – internally assaulted by corruption and drug violence, and externally by the antagonism of the Trump administration. There are new presidential elections on July 1, and López Obrador is participating with the promise to remake Mexico in the spirit of its revolutionary founders. If you can believe the polls, you will definitely win.

In March, the candidate had a meeting with hundreds of supporters, in a conference room in Culiacán. Lopez Obrador, known throughout Mexico as AMLO, is a tall, slender man of sixty-four, with a clean, neat young face, silver hair, and ample gait. When he came in, his supporters stood up and chanted, "It's an honor to vote for López Obrador!" Many of them were farmers, wearing straw hats and worn boots. He urged them to install party observers in the polls to avoid fraud, but warned against buying votes, a habit long established by the PRI. "That's what we get rid of," he said. He promised a "sober and austere government – a government without privileges". López Obrador frequently uses "privilege" as a term of contempt, with "the elite" and, above all, "the mafia of power" as he describes his enemies in political and commercial circles. "We will lower the salaries of those at the top to raise the salaries of those below," he said, adding a biblical certainty: "All we are going to accomplish." López Obrador spoke in a warm voice, leaving long pauses and using simple sentences that ordinary people would understand. He has a tendency to repeat rhymes and slogans, and sometimes the crowd joined, as fans at a pop concert. When he said, "We will not allow the mafia to take power …" A man in the audience ended his sentence, "keep flying". Working together, Lopez Obrador said, "we will make history."

***

The current Mexican government is headed by center-right president Enrique Peña Nieto. His party, the PRI, introduced López Obrador as a radical populist, in the tradition of Hugo Chávez, and warned that he intended to convert Mexico to Venezuela. The Trump administration was also worried. Roberta Jacobson, who was until last month ambassador of the United States to Mexico, told me that US officials often voiced their concern: "They were catastrophic about AMLO, saying "If he wins, the worst will happen." 19659007] Ironically, his growing popularity may be attributed in part to Donald Trump.A few days after Trump's election, Mexican political analysts predicted that their belligerence Open to Mexico would encourage political resistance.Mentor Tijerina, a prominent survey specialist in Monterrey, said at that time: "The arrival of Trump means a crisis for Mexico, and that will help AMLO. Shortly after taking office, López Obrador published a sales book, called "Hey, Trump" which contained excerpts from harsh speechs.In one of them, he said: "Trump and his advisers are talking about Mexicans In the same way that Hitler and the Nazis were referring to the Jews, just before undertaking the infamous persecution and the abominable extermination. "

Peña Nieto warned his counterparts at the White House that the offending behavior Trump's increased the possibility of a new hostile government – a threat to national security just across the border. If Trump did not modulate his behavior, the election would be a referendum on which the candidate was the most anti-American. In the United States, the warnings worked. At a Senate hearing in April 2017, John McCain said, "If the elections were held tomorrow in Mexico, they would likely have a leftist and anti-American president." John Kelly, who was then chief of national security, was in agreement. "It would not be good for the United States – or for Mexico," he said.

In Mexico, comments like Kelly's seemed to only improve Lopez Obrador's position. "Whenever an American politician opens his mouth to express a negative opinion about a Mexican candidate, it helps," Jacobson said. But she has never been sure that Trump has the same "apocalyptic" vision of AMLO. "There are some traits that they share," he said. "Populism, for starters."

During the campaign, López Obrador criticized the "pharaonic government" of Mexico and promised that, when elected, he would refuse to live in Los Pinos, the presidential residence. Instead, it will open to the public, as a place for ordinary families to go and enjoy.

***

After Jacobson's arrival in Mexico in 2016, she organized meetings with local political leaders. López Obrador made it wait for months. Finally, he invited him to his home, in a remote and obsolete corner of Mexico City. "I had the impression that he had done that because he did not think I would go," he said. "But I said," No problem, my security men can do this job. "The Jacobson team followed his instructions in a two-story house without exception in Tlalpan, a middle-class neighborhood." If part of the plan was to show me how modestly he lived, he succeeded. "

López Obrador was" friendly and reliable, "he said, but he misappropriated many of his questions and spoke vaguely about politics.The conversation did little to resolve the question of whether he was a opportunist reformist or a reformer of principle. "What should we expect from him as president?" she said. "Honestly, my strongest feeling about it is that we do not know what to expect "

***

This spring, when López Obrador and his team were traveling across the country, I joined them several times.In the campaign, his style is significantly different from that of most politicians in the country, which often arrive at camp stopovers do in helicopters and move around the streets surrounded by security guards. López Obrador flies in economy class, and travels from town to town in a caravan of two cars, with drivers acting as unarmed bodyguards; there is no other security measure in place, with the exception of inconsistent efforts to hide the name of the hotel in which it is hosted. In the street, people approach him constantly to ask for photos, and he welcomes them all with serenity, presenting a warm and slightly impenetrable facade. "AMLO is like an abstract painting, you see what you want to see," said Luis Miguel González, editorial director of the newspaper El Economista, and one of his characteristic gestures during the speeches is to show that he is an artist. affection by squeezing the crowd and leaning it.

Jacobson recalled that after the election of Trump, López Obrador lamented: "The Mexicans will never choose anyone who "It's not a politician." It was revealing, she thought. "He is clearly a politician," he said. "But, like Trump, he has always been portrayed as External. "He was born in 1953, into a family of traders from the state of Tabasco, in a town called Tepetitan Tabasco, in the Gulf of Mexico, and is crossed by rivers that regularly flood their villages; in its climate as in the combativeness of its local politics, it may resemble Louisiana. López Obrador joked, "Politics is a perfect mix of passion and reason. But I'm Tabasco, one hundred percent passion! "His nickname, El Peje, is derived from the pejelagarto – Tabasco's freshwater marlin, an ancestral and primitive fish, with a face similar to that of a crocodile.

López Obrador was a child, his family moved to the state capital, Villahermosa. Later, in Mexico City, he studied political science and public policy at UNAM, the nation 's leading state – funded university, writing his dissertation on the political formation of the country. Mexican state in the nineteenth century. He married Rocío Beltrán Medina, a sociology student from Tabasco, and they had three children. Elena Poniatowska, the most respected woman of Mexican journalism, remembers meeting him when he was young. "He has always been very determined to go to the presidency," he said. "Like an arrow, straight and unbreakable."

For a person with political aspirations, the PRI was then the only serious option. It was founded in 1929 to restore the country after the revolution. In the 1930s, President Lázaro Cárdenas consolidated it as an inclusive party of socialist change; He has nationalized the oil industry and provided millions of acres of land to the poor and dispossessed. Over the decades, the ideology of the party has fluctuated, but its control over power has steadily grown. The presidents elected their successors, in a ritual called dedazo, and the party is assured that they were elected.

***

López Obrador joined the PRI after university and, in 1976, he helped lead a successful Senate campaign for Carlos Pellicer, a poet who was a friend of Pablo Neruda and Frida Kahlo. López Obrador climbed quickly; He spent five years running the Tabasco office of the Instituto Nacional Indigenista, then heading a department of the National Consumer Institute in Mexico City. But he felt more and more that the party had deviated from its roots. In 1988, he joined a group of leftist dissidents, led by the son of Lázaro Cárdenas, who became the Party of the Democratic Revolution. López Obrador became the leader of the party in Tabasco.

In 1994, he made his first attempt to be elected, candidate for governor of the state. He lost against the PRI candidate, whom he accused of having won through fraud. Although a judicial inquiry did not result in a verdict, many Mexicans believed it; The PRI has a long history of fraudulent elections. Shortly after the elections, a supporter handed López Obrador a box of receipts, proving that the PRI had spent ninety-five million dollars on an election in which half a million people voted.

In 2000, he was elected Mayor of Mexico, a position that gave him considerable power, as well as visibility at the national level. Once elected, he 's built a reputation for simple and disheveled man; He drove an old Nissan to work, arrived before dawn and reduced his own salary. (When his wife died of lupus, in 2003, there was a great show of sympathy). He was not an enemy of the political fight. After one of his officials was recorded apparently by accepting a bribe, he argued that it was a trap, and distributed comics that showed him fighting against them. dark forces. (The grievor was acquitted later). Sometimes López Obrador ignored his assembly and ruled by decree. But he is also shown capable of engaging. He managed to create a pension fund for elderly residents, to enlarge the roads to reduce traffic congestion and to design a public-private project, with telecommunications magnate Carlos Slim, to restore the historic center.

Get ready for the 2006 presidential election, had high levels of approval and a reputation for accomplishing things. (He also had a new wife, a historian named Beatriz Gutiérrez Müller, and now they have an eleven-year-old son). López Obrador saw an opportunity. In the last election, the PRI lost its long power control when the National Action Party won the presidency. The PAN, a conservative traditionalist party, had the backing of the business community, but its candidate, Felipe Calderón, was a small charismatic figure.

The campaign was fiercely contested. Opponents of Lopez Obrador have published television commercials describing him as a misleading populist depicting "a danger to Mexico" and showing images of human misery alongside portraits of Chávez, Fidel Castro and Evo Morales. In the end, Lopez Obrador lost half of one percent of the vote, a margin close enough to raise suspicions of fraud. Refusing to recognize Calderon's victory, he led a demonstration in the capital, where his supporters stopped traffic, built tents and held rallies in the historic Zócalo and Reforma streets. A resident recalled his speeches in "a language that evoked the French Revolution". At one point, he led a parallel takeover in which his supporters were sworn in as president. The demonstrations lasted months and the inhabitants of Mexico became impatient; Finally, López Obrador packed his things and went home.

In the 2012 elections, he won a third of the vote – not enough to beat Peña Nieto, who brought the PRI back to power. But the government of Peña Nieto has been marked by corruption and human rights scandals. Since Trump announced his candidacy with a surge of anti-Mexican rhetoric, Peña Nieto has been trying to appease him, with embarrassing results. He invited Trump to Mexico during his campaign and treated him like he was already a chief of state, only to return to the United States and tell a multitude of supporters that Mexico " will pay for the wall. "

After the election of Trump, Peña Nieto appointed his Foreign Minister, Luis Videgaray, who is a friend of Jared Kushner, so that the management of the relationship with the White House is his absolute priority. "Peña Nieto has been extremely accommodating," said Jorge Guajardo, a former Mexican ambassador to China. "There is nothing that Trump has even hinted that he would not comply with immediately."

****

In early March, before the official start of López Obrador's campaign, we crossed northern Mexico, where resistance to him is concentrated. Its support base is in the poorest and most agrarian south, with its predominantly indigenous population. The north, near the Texas border, is more conservative, economically and culturally linked to the southern United States; his task was not so different from that of the Houston Chamber of Commerce

During the speeches, he tried to downplay the accusations of his opponents, joking about receiving "Russian gold in a submarine "and calling" Andrés Manuelovich ". In Delicias, an agricultural center in Chihuahua, he vowed not to exceed his mandate. "I'm going to work sixteen hours a day instead of eight, so I'm going to do twelve years of work in six," he said. This rhetoric has been supported by more pragmatic measures. Traveling north, he was accompanied by Alfonso (Poncho) Romo, a wealthy businessman from the Monterrey Industrial Zone, whom López Obrador had chosen as future Chief of Staff. A councilor said, "Poncho is the key to the campaign in the North. Poncho is the bridge. "In Lopez Obrador, López Obrador said:" Poncho is with me to help convince the entrepreneurs who told us that we are like Venezuela, or with the Russians, that we want to expropriate the property, and that we are populist But none of this is true – it's a government made in Mexico. "

***

At a lunch with businessmen in Culiacán, the capital of the state of Sinaloa, López Obrador tried some ideas." What we want to do, it's to perform the transformation that this country needs, "he began." Things can not continue as they are. "He spoke in a conversational tone, and the crowd seemed gradually more understanding. "We will end the corruption, impunity and privileges of a small elite," he said. "Once we do, the leaders of this countries can regain their moral and political authority. And we will also clean up Mexico's image in the rest of the world, because right now all that Mexico is known about is violence and corruption. "

López Obrador spoke of helping the poor, but when he spoke of corruption He focused on the political class." Five million pesos a month in pensions for former presidents! " He said, wincing, "All that must end." He pointed out that there were hundreds of presidential aircraft and helicopters, and he said, "We will sell them to Trump. "The audience laughed and added," We will use the money from the sale for public investment, and so will encourage private investment to create employment. "

During these early events, López Obrador adjusted his message as his campaign strategy seemed simple: to make many promises and to negotiate any alliance necessary to be elected, just as he promised the members of his party that he would increase workers' wages at the expense of high-level bureaucrats he promised s to employers not to raise taxes on fuel, drugs or electricity and vowed never to confiscate property. "We will not do anything that goes against freedoms," he said. He proposed to establish a free zone along the thirty-kilometer northern border and to reduce taxes for Mexican and American companies that have established factories there. He also offered government sponsorship, promising to complete an unfinished dam project in Sinaloa and provide agricultural subsidies. "The term" subsidy "has been demonized," he said. "But it's necessary.In the United States they do it – up to one hundred percent of the cost of production."

***

Culiacán is a former bastion of the brutal cartel of Sinaloa, who played a role in the flood of violence and corruption with drugs, sank the Mexican state. Since 2006, the country has waged a "war on drugs" that cost at least a hundred thousand lives, apparently with very little effect. López Obrador, like his opponents, struggled to articulate a viable security strategy.

After lunch in Culiacán, he answered questions, and a woman stood up to ask what she was going to do with drug trafficking. Would you consider the legalization of drugs as a solution? A few months earlier, he had said, apparently without much deliberation, that he could offer an "amnesty" to bring low-level traffickers and producers to legal employment. When the critics jumped at his comment, his advisers tried to deflect criticism by arguing that since none of the current administration 's policies had worked, it was worth trying everything. To the wife of Culiacán, she said: "We will attack the causes with programs for young people, new employment opportunities, education and assistance in the field abandoned. We will not only use force. We will analyze everything and explore all the ways that will enable us to achieve peace. I do not exclude anything, not even legalization, nothing. The crowd applauded and AMLO was relieved.

***

For opponents of López Obrador, his ability to inspire hope is worrisome. Enrique Krauze, historian and commentator who has often criticized the left, said: "It comes directly to the religious sensibilities of the people, they see him as a man who will save Mexico from all its ills. also believes it. "

Krauze has been concerned by López Obrador since 2006. Prior to the presidential election this year, he published an essay titled" The Tropical Messiah ", in which he writes that AMLO had a L & # Religious enthusiasm was "puritanical, dogmatic, authoritarian, inclined to hatred and, above all, redeeming". Krauze's latest book "The people I am" deals with the dangers of populism. He examines political cultures in Venezuela and Cuba, and also includes a scathing assessment of Donald Trump, whom he calls "Caligula on Twitter." In the preface, he writes about López Obrador in a tone of oracular consternation. "I think if he wins, he will use his charisma to promise a return to an Arcadian order," he says. "And with this accumulated power, arrived thanks to democracy, it will corrupt the democracy of the interior."

What worried Krauze, he explained, was that if López Obrador's party won big, not just the presidency but also a majority in Congress, which, according to polls, is likely to change the composition of the Supreme Court and dominate other institutions. It could also exercise tighter control over the media, many of which are backed by state-sponsored advertising. "Are you going to ruin Mexico?" Krauze asked. "No, but it could hinder Mexico's democracy by eliminating its counterweight."

We have had a democratic experience for eighteen years since the PRI lost power for the first time in 2000. It is flawed. criticize, but there have also been positive changes. I'm worried that with AMLO this experience will end. "

One night, during dinner at Culiacán, López Obrador took a taco of meat and spoke of his antagonists to the right, alternating between amusement and anxiety.A few days earlier, Roberta Jacobson had announced that he had not been able to do anything. she would resign as an Ambassador, and the Mexican government had immediately supported a possible replacement: Edward Whitacre, former General Motors General Manager who turned out to be a friend of the tycoon Carlos Slim. a complicated point for López Obrador He had recently discussed with Slim a multi-million dollar plan for a new airport in Mexico City, in which Slim was involved.The plan was a public-private venture with the Peña government Nieto, and López Obrador, alleging corruption, had promised to stop it. (The government denies any illegal act). "We hope this does not mean that they plan to interfere with it. me, "said Lopez Obrador, Whitacre and Slim. "Recently, Peruvian novelist and politician Mario Vargas Llosa – who serves as an oracle for the Latin American right – has publicly stated that if AMLO is elected, it would be" a huge setback for democracy. " in Mexico. He added that he hoped the country would not commit suicide on election day. When I mentioned the comments, López Obrador smiled and said that Vargas Llosa was in the news mainly because of her marriage to "a woman who had always been married by status, and was still in Hola magazine! " He was referring to the socialite Isabel Preysler, an ex-wife of singer Julio Iglesias, for whom Vargas Llosa had abandoned his fifty-year marriage. López Obrador asked me if I had seen his answer, in which he had called Vargas Llosa a good writer and a bad politician. "You realize," he said mischievously, "I did not call him a great writer."

***

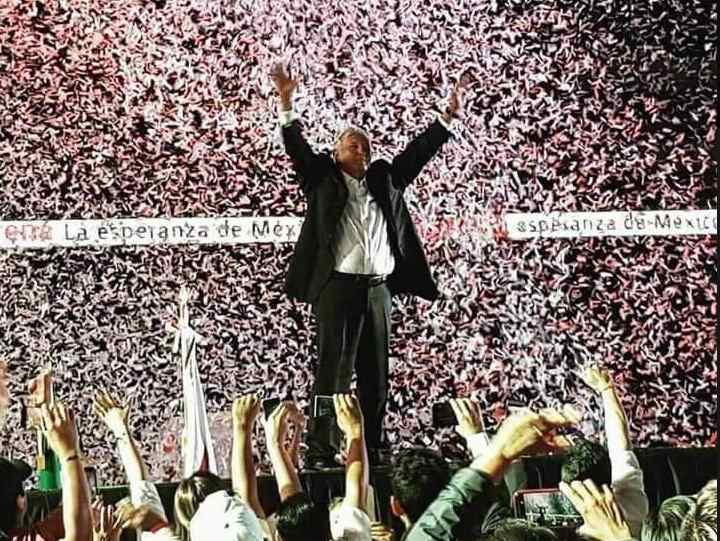

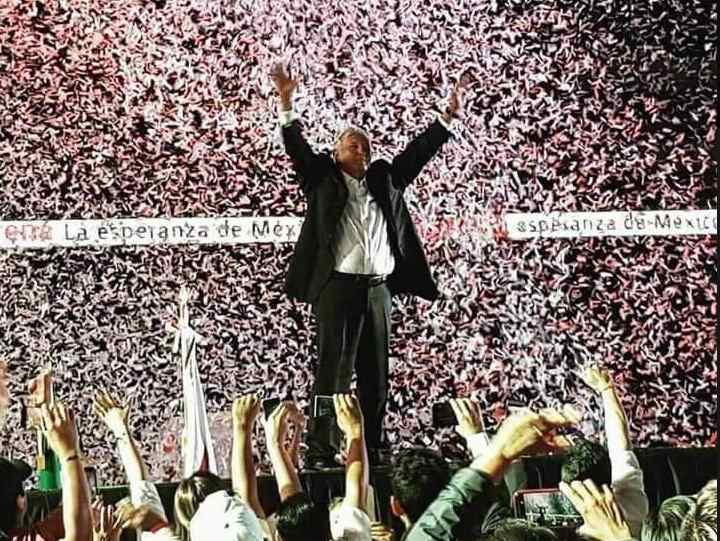

On April 1, López Obrador officially launched his campaign in front of a crowd of several thousand people in Ciudad Juarez. On a stage in a square, he was standing with his wife, Beatriz, and several of his cabinet candidates. "We came here to start our campaign, where our homeland begins," he said. The scene was beneath a large statue of the revered 19th-century Mexican ruler Benito Juárez, a well-known hero of López Obrador. Juarez, a man of Zapotec origin, humble, who defended the cause of people deprived of their rights, is a kind of figure of Abraham Lincoln in Mexico, an inflexible and persistent emblem of honor . Looking at the statue, López Obrador said that Juarez was "the best president that Mexico has had."

In the speech, López Obrador compared the current administration with the despots and settlers who had controlled the country before the revolution. He attacked the "colossal dishonesty" which, he said, had characterized the "neoliberal" policies of the last Mexican governments. "The leaders of the country have dedicated themselves … to grant the national territory," he said. With his presidency, the government "would cease to be a factory that produces the new rich of Mexico."

López Obrador often speaks of admiring the leaders of the 1930s – including Lázaro Cárdenas – and much of his social program recalls the initiatives of those years. In his opening speech, he said that he intended to develop the southern part of the country, where the agricultural economy was devastated by cheap imports of American food products. . To do this, he proposed planting millions of trees to obtain fruit and timber, and build a high-speed tourist train that would link the beaches of the Yucatan Peninsula to the Mayan ruins. Only the tree planting project would create four hundred thousand jobs, he predicts. With these initiatives, he said, people in the South could stay in their villages and not have to travel north to work.

Throughout the country, he would encourage construction projects using hand tools rather than modern ones. stimulate the economy in rural communities. Pensions for the elderly would double. There would be free internet in Mexican schools and in their public spaces. Young people would receive scholarships and then jobs after graduation. I wanted "trainees yes, sicarios no."

For many, especially in the south, these propositions are attractive. When López Obrador is asked how he will pay for them, he tends to offer an equally seductive answer. "This is not a problem!" He said in a speech. "There is money, what there is, it is corruption, and we are going to stop it." In getting rid of the official corruption, he calculated that Mexico could save ten percent of its national budget. Corruption is a major problem for López Obrador. Marcelo Ebrard, his main political ally, asserts that his ethics is based on a "Calvinist current," and even some skeptics have been persuaded of his sincerity. Cassio Luiselli, a long-time Mexican diplomat, said to me, "I do not like his authoritarian style and confrontational style." However, he added, "I think it's an honest man, which is a lot to say in these areas. 19659007] López Obrador promised that his first bill in Congress will amend an article of the constitution that prevents Mexican presidents from being tried for corruption. Ce serait un élément de dissuasion symbolique, mais insuffisant; Pour éradiquer la corruption, il faudrait éliminer d'énormes pans de gouvernement. L'année dernière, l'ancien gouverneur de Chihuahua, accusé de détournement de fonds, s'est enfui aux États-Unis, où il a évité les efforts d'extradition. Plus d'une douzaine de gouverneurs actuels et anciens ont fait l'objet d'enquêtes criminelles. Le procureur général qui dirigeait certaines de ces enquêtes aurait fait enregistrer une Ferrari à son nom dans une maison inoccupée dans un autre État, et bien que son avocat ait fait valoir qu'il s'agissait d'une erreur administrative, il a démissionné peu de temps après. L'ancien chef de la compagnie pétrolière nationale a été accusé d'accepter des millions de dollars de pots-de-vin (il le nie). Peña Nieto, qui s'est présenté comme un réformateur, a été impliqué dans un scandale dans lequel sa femme a obtenu une maison de luxe d'un constructeur avec des connexions au gouvernement; Plus tard, son administration a été accusée d'utiliser la technologie pour espionner ses adversaires. Selon le rapport du Times, les procureurs ont refusé de rechercher des preuves tangibles contre les fonctionnaires du PRI pour éviter d'endommager les possibilités électorales du parti.

Avec chacun des principaux partis impliqués dans la corruption, les partisans de López Obrador semblent S'inquiéter moins sur la praticabilité de leurs idées que sur leurs promesses de réparer un gouvernement brisé. Emiliano Monge, romancier et essayiste de renom, a déclaré: «Cette élection a vraiment commencé à cesser d'être politique il y a quelques mois et elle est devenue émotionnelle. C'est avant tout un référendum contre la corruption, dans lequel, à la fois par droit et par ruse, AMLO s'est présentée comme la seule alternative. Y en realidad lo es.”

***

Durante meses, el equipo de López Obrador recorrió el país. Al llegar a una pequeña ciudad vacuna llamada Guadalupe Victoria, me dijo que había estado allí veinte veces. Después de un largo día de discursos y reuniones en Sinaloa, cenamos mientras él se preparaba para viajar a Tijuana, donde tenía una agenda similar al día siguiente. Parecía un poco cansado, y le pregunté si estaba planeando un descanso. Él asintió y me dijo que, durante la Pascua, él iría a Palenque, en el sureño estado de Chiapas, donde tenía un ranchito en el bosque. “Voy allí y no salgo otra vez durante tres o cuatro días,” dijo. “Solo miro los árboles.”

En su mayor parte, sin embargo, comunicarse con las multitudes parece energizarlo. En Delicias, le llevó veinte minutos caminar una sola cuadra, mientras los partidarios presionaban por selfies y besos, y sostenían carteles que decían “AMLOve”—uno de los eslóganes de su campaña. La presencia con sus oponentes y los encuentros con los medios le interesan menos. A veces, ha respondido a las preguntas enérgicas de los periodistas con un movimiento de su meñique—en México, un no imperativo. En 2006, se negó a asistir al primer debate presidencial; sus oponentes le dejaron una silla vacía en el escenario.

Hubo tres debates programados para esta temporada de campaña, y estaban diseñados para que AMLO perdiera. Para el 20 de mayo, cuando se realizó el segundo, en Tijuana, las encuestas indicaban que tenía un cuarenta y nueve por ciento de los votos. Su rival más cercano—Ricardo Anaya, un abogado de treinta y nueve años que es el candidato del PAN—tenía el veintiocho por ciento. José Antonio Meade, que había servido como secretario de finanzas y secretario de Relaciones Exteriores bajo Peña Nieto, tenía veintiuno. En último lugar, con el dos por ciento, estaba Jaime Rodríguez Calderón, el gobernador del estado de Nuevo León. Un tipo duro e intemperante conocido como El Bronco, que ha dejado su huella en la campaña al sugerir que a los funcionarios corruptos se les deberían cortar las manos.

Con López Obrador a la cabeza, la estrategia de sus oponentes en el debate era hacerlo ver a la defensiva, y a veces funcionaba. En un momento, Anaya, un hombre pequeño con el pelo cortados a ras, y gafas sin montura, como un emprendedor en tecnología, cruzó el escenario para enfrentar a López Obrador. Al principio, AMLO reaccionó suavemente. Buscó su bolsillo y exclamó: “Voy a cuidar mi cartera”. El ánimo se hizo más ligero. Pero cuando Anaya lo desafió en una de sus iniciativas favoritas, una línea de tren que conecta el Caribe y el Pacífico, estaba tan afligido que llamó a Anaya canalla, un sinvergüenza. Continuó, usando la forma diminutiva del nombre de Anaya para crear una frase que rimaba y se burlaba de su estatura: “Ricky, riquín, canallín”.

Cuando Meade, el candidato del PRI, criticó al partido de López Obrador por votar en contra de un acuerdo comercial, AMLO respondió que el debate no era más que una excusa para atacarlo. “Es obvio, y, diría, comprensible,” dijo. “Estamos liderando por veinticinco puntos en las encuestas.” De lo contrario, apenas se molestó en mirar hacia Meade, excepto para saludar con desdén a él y a Anaya y llamarlos representantes de “la mafia del poder.”

Sin embargo, su ventaja en las encuestas solo creció. Dos días más tarde, en la ciudad turística de Puerto Vallarta, miles de fanáticos rodearon su camioneta, manteniéndola en el lugar hasta que la policía abrió un camino. En redes sociales, circularon videos de simpatizantes inclinándose para besar su auto.

***

Desde que perdió las elecciones de 2006, López Obrador se ha presentado como un avatar del cambio. Fundó un nuevo partido, el Movimiento Regeneración Nacional, o Morena, que Duncan Wood, el director del Instituto de México en el Wilson Center, describió como evocador del PRI al principio—-un esfuerzo por atraer a todos los que sentían que México se había descarriado. “Recorrió el país firmando acuerdos con personas,” dijo Wood. “‘¿Quieres ser parte de un cambio? ¿Sí? Entonces firme aquí.’ Morena tiene un número creciente de simpatizantes pero relativamente pocos miembros oficiales; el año pasado, tenía trescientos veinte mil, convirtiéndolo en el cuarto partido más grande del país. Como la campaña de López Obrador se había fortalecido, ha dado la bienvenida a socios que parecen profundamente incompatibles. En diciembre, Morena forjó una coalición con el Partido del Trabajo (PT), un partido con orígenes maoístas; y también se unió al Partido Encuentro Social (PES), un partido cristiano evangélico que se opone al matrimonio entre personas del mismo sexo, la homosexualidad y el aborto. Algunos de sus colaboradores piensan que López Obrador podría romper estos vínculos después de que gane, pero no todos están convencidos. “Lo que más me aterra son sus alianzas políticas,” me dijo Luis Miguel González, de El Economista.

En un evento, en el pueblo de Gómez Palacio, algunas de estas alianzas chocaron desordenadamente. En un mercado al aire libre a las afueras de la ciudad, partidarios del PT ocuparon una gran área cerca del escenario—un bloque organizado de hombres jóvenes que vestían camisetas rojas y ondeaban banderas con estrellas amarillas. En el escenario con López Obrador estaba el jefe del partido, Alberto “Beto” Anaya. Uno de los miembros del equipo de López Obrador hizo una mueca visible y refunfuñó: “Ese tipo tiene bastantes escándalos de corrupción.” (Anaya niega las acusaciones contra él). Mientras los líderes locales se juntaban, una mujer joven se acercó al micrófono y los abucheos estallaron entre la multitud. El miembro del equipo de AMLO explicó que la mujer era Alma Marina Vitela, una candidata de Morena que anteriormente había estado con el PRI. Los abucheos cobraron fuerza, y Vitela se quedó congelada, mirando a la multitud, aparentemente incapaz de hablar. López Obrador se acercó, la abrazó y tomó el micrófono. “Tenemos que dejar atrás nuestras diferencias y conflictos,” dijo. El abucheo se detuvo rápidamente. “¡La patria es primero!,” gritó, y estallaron los gritos de alegría.

Con los partidarios del PT en la audiencia, el discurso de López Obrador tomó un camino claramente más radical. “Esta fiesta es un instrumento para la lucha del pueblo,” dijo, y agregó: “En la unión está la fuerza”. Continuó, “México producirá todo lo que consume. Dejaremos de comprar en el extranjero.” Después de cada uno de sus puntos, los militantes del PT vitorearon al unísono, y alguien golpeaba un tambor.

Durante la cena de esa noche, hablamos sobre los prospectos de Morena. López Obrador se jactó de que, aunque el partido sigue siendo considerablemente más pequeño que sus rivales, fue capaz de movilizar de manera confiable a sus partidarios. “Hay pocos movimientos en la izquierda en América Latina aún con el poder de poner a la gente en la calle”, dijo.

Hace poco, un prominente líder comunista en la región me había dicho que la izquierda latinoamericana había muerto en gran parte, porque ya casi no había sindicatos. Los sindicatos alguna vez fueron una fuente de poder de la política regional, proporcionando credibilidad y votos; en las últimas décadas, muchos han sucumbido a la corrupción o divisiones internas, o han sido cooptados por los dueños de negocios. López Obrador sonrió cuando lo mencioné. El sindicato de mineros más grande de México había ofrecido recientemente apoyar su campaña. En 2006, el jefe del sindicato, Napoleón Gómez Urrutia, fue acusado de intentar malversar un fondo fiduciario de trabajadores de cincuenta y cinco millones de dólares; él huyó a Canadá, donde obtuvo la ciudadanía y escribió un best-seller sobre sus grandes esfuerzos. En la versión de López Obrador, había sido castigado por enfrentarse a los dueños de las minas. “Son dueños de todo, y tienen la última palabra,” dijo.

Gómez Urrutia fue exonerado en 2014, pero aún sentía que era vulnerable a nuevos cargos si regresaba. López Obrador tomó su causa, ofreciéndole un asiento en el Senado, lo que le daría inmunidad de enjuiciamiento. Los críticos de López Obrador se enfurecieron. “¡Deberías haber visto la indignación!,” dijo. “Realmente me atacaron”. Pero ya se está bajando,” con una mirada burlona dijo: “Les dije que, si los canadienses pensaban que estaba bien, entonces tal vez no era tan malo después de todo.” Moviendo sus ojos, dijo, “Ya sabes, aquí creen para todo que los canadienses son buenos.”

López Obrador me dijo que también tenía el respaldo del sindicato de maestros, y luego se apresuró a aclarar: “El no oficial—no el corrupto.” El gobierno de Peña Nieto había aprobado reformas educativas, y las medidas habían sido impopulares entre los docentes. “Ahora están con nosotros,” dijo, y luego agregó: “El sindicato oficial—corruptos y comprados— también me ha dado su apoyo.” Hizo una mueca. “Este es el tipo de apoyo que uno realmente no necesita, pero en una campaña se necesita apoyo, entonces vamos a seguir adelante, y esperamos encontrar formas de limpiarlos”.

***

Unas semanas más tarde, me volví a unir a López Obrador en la carretera de Chihuahua, el estado más grande de México. Al sur de Ciudad Juárez y su cinturón polvoriento de fábricas de bajos salarios, Chihuahua es un pueblo de vaqueros—un lugar abierto, de vastas praderas y montañas boscosas. Durante varios días, condujimos cientos de millas de ida y vuelta por los pastizales.

Este territorio había sido una vez una base para el ejército revolucionario de Pancho Villa en su lucha contra el dictador Porfirio Díaz; el paisaje estaba salpicado de sitios de batallas y ejecuciones masivas. Un día, afuera de un baño de hombres en una parada, López Obrador miró hacia afuera a la llanura, agitó los brazos y dijo: “Villa y sus hombres marcharon por todas estas partes durante años. Pero solo imagínense la diferencia: él y sus hombres cubrieron la mayor parte de estas millas a caballo, mientras nosotros estamos en carros.”

López Obrador ha escrito media docena de libros sobre la historia política de México. Incluso más que la mayoría de los mexicanos, él es consciente de la historia de subyugación del país, y sensible a sus ecos en la retórica de la administración Trump. Cuando nos detuvimos a almorzar en un modesto restaurante en la carretera, habló de la invasión de 1846, conocida en los Estados Unidos como la Guerra México-Americana y en México como la intervención de los Estados Unidos en México. Ese conflicto terminó con la humillante cesión de más de la mitad del territorio de la nación a los Estados Unidos, pero López Obrador vio en ella al menos algunos ejemplos de valor. En un momento durante la guerra, dijo, el oficial Matthew Perry desplegó una gran flota de los EU frente a la costa de Veracruz. “Tenía una superioridad abrumadora y envió un mensaje al comandante de la ciudad para que se rindiera, para así salvar a la ciudad y a su gente,” dijo. “¿Y sabes lo que le dijo el comandante a Perry? ‘Mis bolas son demasiado grandes para caber en tu Capitolio. Comienza.” Y entonces Perry abrió fuego y devastó Veracruz.” López Obrador se rió. “Pero el orgullo se salvó.” Por un momento, reflexionó sobre si la victoria era más importante que un gran gesto, que podría significar la derrota. Finalmente, dijo que creía que el gran gesto era importante—”por el bien de la historia, por ninguna otra cosa”.

Fuimos interrumpidos por miembros de la familia que dirigían el restaurante, pidiendo cortésmente una selfie. Cuando López Obrador se puso de pie para aceptar, dijo: “Este país tiene sus personalidades, ¡pero Donald Trump!” levantó las cejas con incredulidad y, con una sonrisa, golpeó la mesa con ambas manos.

Al principio del mandato de Trump, López Obrador se presentó como un antagonista; junto con sus discursos condenatorios, presentó una denuncia en la Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, en Washington, D.C., en protesta por el muro fronterizo de la administración y su política de inmigración. Cuando le mencioné el muro a él, sonrió con desprecio y dijo: “Si sigue adelante, iremos a las Naciones Unidas para denunciarlo como una violación a los derechos humanos.” Pero agregó que había llegado a comprender, de ver a Trump, que “no era prudente abordarlo directamente.”

En la campaña, generalmente se ha resistido a los grandes gestos. Poco antes del discurso en Gómez Palacio, Trump envió tropas de la Guardia Nacional a la frontera con México. López Obrador sugirió una respuesta casi pacifista: “Organizaremos una manifestación a lo largo de toda la frontera—¡Una protesta política, todos vestidos de blanco!.”

La mayoría de las veces, López Obrador ha ofrecido llamadas por el respeto mutuo. “No descartaremos la posibilidad de convencer a Donald Trump de cuán equivocada ha sido su política exterior, y particularmente su actitud despectiva hacia México,” dijo en Ciudad Juárez. “Ni México ni su gente serán una piñata para ninguna potencia extranjera.” Fuera del escenario, sugirió que era moralmente necesario frenar las tendencias aislacionistas de Trump. “Estados Unidos no puede convertirse en un gueto,” dijo. “Sería un absurdo monumental”. Dijo que esperaba poder negociar una nueva relación con Trump. Cuando expresé escepticismo, él señaló los comentarios fluctuantes de Trump sobre el líder de Corea del Norte, Kim Jong Un: “Muestra que sus posiciones no son irreductibles, privilegia las apariencias”. Detrás de escena, los asesores de López Obrador han contactado con sus contrapartes en la administración de Trump, tratando de establecer relaciones de trabajo.

Una posición más agresiva le daría a López Obrador poca ventaja sobre sus oponentes en la campaña. Cuando le pregunté a Jorge Guajardo, el ex embajador, qué papel tenía Trump en este punto en las elecciones, él dijo: “Cero. Y por una razón muy simple—todos en México se oponen a él por igual.” Sin embargo, en el cargo, podría encontrar que está en su interés presentar una resistencia más enérgica. “Mira lo que les sucedió a esos líderes que de inmediato trataron de estar bien con Trump,” dijo Guajardo. “Macron, Merkel, Peña Nieto y Abe—todos salieron perdiendo. ¡Pero mira a Kim Jong Un! A Trump parece gustarle quienes lo rechazan. Y creo que el mismo escenario se aplicará a Andrés Manuel.”

Durantes eventos en la campaña, López Obrador habla a menudo del mexicanismo—una forma de decir “México primero”. Los observadores de la región dicen que, cuando los intereses de los dos países compitan, es probable que él mire hacia adentro. A menudo las fuerzas armadas y la policía de México han tenido que ser persuadidas para cooperar con los Estados Unidos, y probablemente él estará menos dispuesto a presionarlos. Los EE.UU. presionaron a Peña Nieto, con éxito, para endurecer la frontera sur de México contra el flujo de migrantes centroamericanos. López Obrador ha anunciado que en su lugar moverá la sede de inmigración a Tijuana, en el norte. “Los estadounidenses quieren que la coloquemos en la frontera sur con Guatemala, para que hagamos su trabajo sucio por ellos,” dijo. “No, lo pondremos aquí, para que podamos cuidar de nuestros inmigrantes.” Los funcionarios regionales temen que Trump se esté preparando para retirarse del TLCAN. López Obrador, quien a menudo ha pedido una mayor autosuficiencia, podría estar feliz de dejarlo ir. En el discurso que lanzó su campaña, dijo que esperaba desarrollar el potencial del país para que “ninguna amenaza, ningún muro, ninguna actitud de intimidación por parte de ningún gobierno extranjero, jamás nos impida que seamos felices en nuestra propia patria”.

Incluso si López Obrador se inclina por construir una relación más cercana, las presiones tanto dentro como fuera del país podrían evitarlo. “No se puede ser el presidente de México y tener una relación pragmática con Trump; es una contradicción en los términos,” dijo González. “Hasta ahora, México ha sido predecible, y Trump ha sido el que proporciona las sorpresas. Creo que ahora va a ser AMLO el factor sorpresa.”

***

Una mañana en Parral, la ciudad donde murió Pancho Villa, López Obrador y yo desayunamos mientras él se preparaba para un discurso en la plaza. Reconoció que la transformación que Villa había ayudado a realizar había sido sangrienta, pero confiaba en que la transformación que él mismo proponía sería pacífica. “Estoy enviando mensajes de tranquilidad, y voy a seguir haciéndolo,” dijo. “Y, muy aparte de mis diferencias con Trump, lo he tratado con respeto.”

Le dije que muchos mexicanos se preguntaban si había moderado sus primeras creencias radicales. “No,” dijo. “Siempre he pensado de la misma manera. Pero actúo de acuerdo a las circunstancias. Hemos propuesto un cambio ordenado, y nuestra estrategia parece haber funcionado. Ahora hay menos miedo. Se han sumado más personas de clase media, no solo los pobres, y hay gente de negocios también.”

Hay límites a la inclusión de López Obrador. Muchos jóvenes mexicanos metropolitanos desconfían de lo que ven como su falta de entusiasmo por la política de identidad contemporánea. Le pregunté si había sido capaz de cambiar de opinión. “No mucho,” dijo, con total naturalidad. “Mira, en este mundo hay quienes le dan más importancia a la política del momento—identidad, género, ecología, animales. Y hay otro campo, que no es la mayoría, pero que es más importante, que es la lucha por la igualdad de derechos, y ese es el campo al que me suscribo. En el otro campo, se puede pasar la vida criticando, cuestionando y administrando la tragedia sin proponer nunca la transformación del régimen.”

López Obrador a veces dice que quiere ser considerado como un líder de la talla de Benito Juárez. Le pregunté si realmente creía que podía reconstruir el país de una manera tan histórica. “Sí,” respondió. Me miró directamente. “Sí, sí. Vamos a hacer historia, lo tengo claro. Sé que cuando uno es candidato uno a veces dice cosas y hace promesas que no se pueden cumplir—no porque no se quiera, sino por las circunstancias. Pero creo que puedo enfrentar las circunstancias y cumplir esas promesas.”

Este es el mensaje que entusiasma a sus seguidores y preocupa a sus oponentes: una promesa de transformar el país sin quebrarlo. Pensé en un discurso que dio una noche en Ciudad Cuauhtémoc, un pueblo minero descuidado rodeado de montañas. Ciudad Cuauhtémoc estaba alejada de la mayoría de los ciudadanos de México, pero la gente allí sentía las mismas frustraciones con la corrupción y la depredación económica. Según el equipo de López Obrador, el área estaba dominada por cárteles de la droga y la economía era problemática. Un líder local de Morena habló con frustración sobre “compañías mineras extranjeras que explotan los tesoros bajo nuestro suelo.”

La audiencia estaba llena de vaqueros con sombreros y botas; un grupo de mujeres indígenas Tarahumaras estaban a un lado, vistiendo vestidos tradicionales bordados. López Obrador parecía estar en casa, y su discurso tenía más enojo y era menos cauteloso que de costumbre. Prometió a sus oyentes una “revolución radical”, una que les daría el país que querían. “’Radical’ proviene de la palabra ‘raíces'”, dijo. “Y vamos a sacar este régimen corrupto desde las raíces.”

—-FIN—

Este artículo aparece en la edición impresa del número del 25 de junio de 2018, con el titular “México primero.”

*John Lee Anderson, escritor, comenzó a contribuir con la revista en 1998. Es autor de varios libros, entre ellos “The Fall of Bagdad.”

Traducción y revisión: Carla González, Daniel Tovar

Nota del traductor: Las frases entre comillas que fueron dichas en español, han sido traducidas al inglés por el autor del texto original, y traducidas una vez más al español, por lo que el uso de términos específicos puede variar de la realidad.

Texto original:

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/06/25/a-new-revolution-in-mexico

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/06/25/a-new-revolution-in-mexico

Si quieres informarte más, visita: Regeneración

loading…

[ad_2]

Source link