[ad_1]

New observations with the European Southern Observatory’s Very large telescope (THIS‘s VLT) indicate that the rogue comet 2I / Borisov, which is only the second and most recent detected interstellar visitor to our solar system, is one of the most pristine ever seen. Astronomers suspect that the comet probably never passed near a star, making it an intact relic of the cloud of gas and dust from which it formed.

2I / Borisov was discovered by amateur astronomer Gennady Borisov in August 2019 and was confirmed to come from beyond the solar system a few weeks later. “2I / Borisov could represent the first truly pristine comet ever to be observed,” says Stefano Bagnulo of the Armagh Observatory and Planetarium in Northern Ireland, UK, who led the new study published today in Nature communications. The team estimates that the comet had never passed near a star before flying near the Sun in 2019.

New observations with the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT) indicate that rogue comet 2I / Borisov, which is only the second and most recently detected of interstellar visitors to our solar system, is one of the most pristine ever observed. This video summarizes the new discoveries about this mysterious alien visitor. Credit: ESO

Bagnulo and his colleagues used the FORS2 instrument on ESO’s VLT, located in northern Chile, to study 2I / Borisov in detail using a technique called polarimetry.[1] As this technique is regularly used to study comets and other small bodies in our solar system, it allowed the team to compare the interstellar visitor with our local comets.

The team found that 2I / Borisov had polarimetric properties distinct from those of solar system comets, with the exception of Hale – Bopp. Comet Hale – Bopp garnered a lot of public interest in the late 1990s because it was easily visible to the naked eye and also because it was one of the most pristine comets that astronomers have ever seen. views. Prior to its most recent passage, Hale-Bopp is believed to have passed through our Sun only once and therefore had hardly been affected by solar wind and radiation. This means it was pristine, with a composition very similar to the cloud of gas and dust – and the rest of the solar system – formed around 4.5 billion years ago.

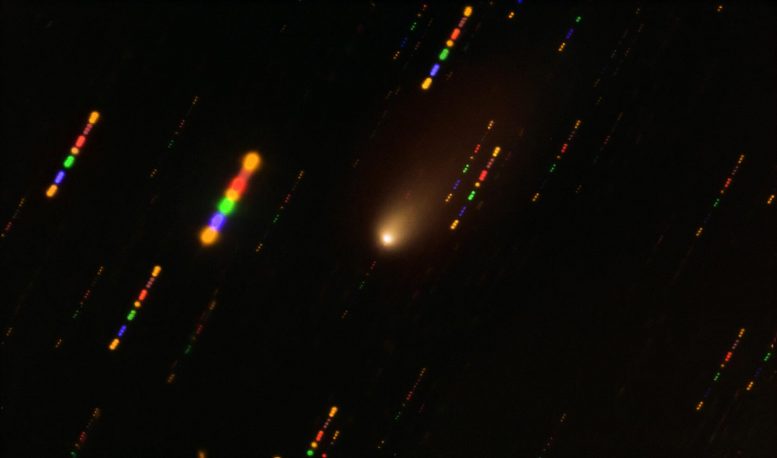

This image was taken with the FORS2 instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope at the end of 2019, when comet 2I / Borisov passed close to the Sun. As the comet moved at a breakneck speed, about 175,000 kilometers per hour, the background stars appeared as trails of light as the telescope followed the comet’s path. The colors of these streaks give the image a disco touch and are the result of the combination of observations in different bands of wavelengths, highlighted by the different colors of this composite image. Credit: ESO / O. Hainaut

By analyzing the polarization with the color of the comet to gather clues about its composition, the team concluded that 2I / Borisov is in fact even more pristine than Hale – Bopp. This means that it bears untarnished signatures of the cloud of gas and dust from which it formed.

“The fact that the two comets are remarkably similar suggests that the environment in which 2I / Borisov originated is not that different in its makeup from the environment at the start of the solar system,” says Alberto Cellino, co-author of the study, from the Turin Astrophysical Observatory, National Institute of Astrophysics (INAF), Italy.

Olivier Hainaut, an astronomer at ESO in Germany who studies comets and other near-Earth objects but was not involved in this new study, agrees. “The main result – that 2I / Borisov is unlike any other comet except Hale-Bopp – is very strong,” he says, adding that “it is very plausible that they formed under conditions very similar. “

This image shows an artist’s impression of what the surface of comet 2I / Borisov might look like. 2I / Borisov was a visitor from another planetary system that passed through our Sun in 2019, allowing astronomers a unique view of an interstellar comet. While telescopes on Earth and in space have captured images of this comet, we have no close observations of 2I / Borisov. So it’s up to artists to come up with their own ideas of what the comet’s surface might look like, based on the scientific information we have about it. Credit: ESO / M. Kormesser

“The arrival of 2I / Borisov from interstellar space represented the first opportunity to study the composition of a comet from another planetary system and to verify whether the material that comes from this comet is somehow different from our native variety, ”says Ludmilla Kolokolova, of the University of Maryland in the United States, who participated in the Nature Communications research.

Bagnulo hopes astronomers will have another, even better, opportunity to study a rogue comet in detail before the decade is out. “ESA plans to launch Comet Interceptor in 2029, which will have the ability to reach another visiting interstellar object, if an object on an appropriate trajectory is discovered,” he said, referring to an upcoming mission from the European Space Agency.

This image shows an artist’s close-up view of what the comet’s surface might look like. Credit: ESO / M. Kormesser

An origin story hidden in the dust

Even without a space mission, astronomers can use Earth’s many telescopes to better understand the different properties of rogue comets like 2I / Borisov. “Imagine how lucky we were that a comet from a system light years away simply made a trip to our doorstep by chance,” says Bin Yang, an astronomer at ESO in Chile, who has also benefited from the passage of 2I / Borisov through our Solar. System to study this mysterious comet. The results of his team are published in Nature Astronomy.

Yang and his team used data from the Atacama Large Millimeter / submillimeter Array (ALMA), in which ESO is a partner, as well as ESO’s VLT, to study the dust grains of 2I / Borisov in order to gather clues about the comet’s birth and the conditions in its home system.

This animation shows the orbit (in red) of interstellar comet 2I / Borisov, which was the second and most recently detected interstellar object to visit our solar system. Credit: ESA / Space Engine (spaceengine.org) / L. Calçada. Music: Johan B. Monell

They found that the 2I / Borisov coma – a dust envelope surrounding the main body of the comet – contains compact pebbles, grains of about a millimeter or more. In addition, they found that the relative amounts of carbon monoxide and water in the comet changed dramatically as it approached the Sun. The team, which also includes Olivier Hainaut, says this indicates that the comet is made up of materials that formed in different places in its planetary system.

The observations of Yang and his team suggest that the matter in the planetary house of 2I / Borisov was mixed from near his star to farther away, possibly due to the existence of giant planets, whose strong gravity stirs the material in the system. Astronomers believe a similar process occurred early in the life of our solar system.

Although 2I / Borisov was the first rogue comet to pass the Sun, it was not the first interstellar visitor. The first interstellar object to be observed passing through our solar system was ʻOumuamua, another object studied with ESO’s VLT in 2017. Initially classified as a comet, ʻOumuamua was later reclassified as an asteroid because it lacked coma.

This video shows an artist’s take on what the comet’s surface might look like. 2I / Borisov was a visitor from another planetary system that passed through our Sun in 2019, allowing astronomers a unique view of an interstellar comet. While telescopes on Earth and in space have captured images of this comet, we have no close observations of 2I / Borisov. So it’s up to artists to come up with their own ideas of what the comet’s surface might look like, based on the scientific information we have about it. Credit: ESO / M. Kormesser

Remarks

- Polarimetry is a technique for measuring the polarization of light. Light becomes polarized, for example, when it passes through certain filters, such as the lenses of polarized sunglasses or cometary material. By studying the properties of the dust polarized sunlight of a comet, researchers can learn about the physics and chemistry of comets.

More information

This research highlighted in the first part of this press release was presented in the article “Unusual polarimetric properties of interstellar comet 2I / Borisov” to appear in Nature communications (doi: 10.1038 / s41467-021-22000-x). The second part of the press release highlights the study “Compact pebbles and the evolution of volatiles in interstellar comet 2I / Borisov” to appear in Nature astronomy (doi: 10.1038 / s41550-021-01336-w).

The team that carried out the first study is made up of S. Bagnulo (Armagh Observatory & Planetarium, UK [Armagh]), A. Cellino (INAF – Osservatorio Astrofisico di Torino, Italy), L. Kolokolova (Department of Astronomy, University of Maryland, United States), R. Nežic (Armagh; Mullard Space Science Laboratory, University College London, Kingdom United; Center for Planetary Science, University College London / Birkbeck, United Kingdom, T. Santana-Ros (Departamento de Fisica, Ingeniería de Sistemas y Teoría de la Señal, Universidad de Alicante, Spain; Institut de Cences del Cosmos, Universitat de Barcelona, Spain), G. Borisov (Armagh; Institute of Astronomy and National Astronomical Observatory, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Bulgaria), AA Christou (Armagh), Ph. Bendjoya (University of Côte d’Azur, Côte d’Azur Observatory, CNRS, Lagrange Laboratory, Nice, France) and M. Devogele (Arecibo Observatory, University of Central Florida, United States).

The team that conducted the second study is made up of Bin Yang (European Southern Observatory, Santiago, Chile [ESO Chile]), Aigen Li (Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Missouri, Colombia, USA), Martin A. Cordiner (Laboratory of Astrochemistry, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, USA and Department of Physics, Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, USA), Chin-Shin Chang (ALMA Joint Observatory, Santiago, Chile [JAO]), Olivier R. Hainaut (European Southern Observatory, Garching, Germany), Jonathan P. Williams (Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai’i, Honolulu, USA [IfA Hawai‘i]), Karen J. Meech (IfA Hawai’i), Jacqueline V. Keane (IfA Hawai’i) and Eric Villard (JAO and ESO Chili).

[ad_2]

Source link