[ad_1]

No filmmaker has used the Director’s Cut format better than Francis Ford Coppola. Rather than disentangling and truncating the first two Godfather films for network television in the 1970s, Coppola restructured them into a single chronological saga – running for seven hours and featuring plenty of new footage – which allowed viewers to get a more direct perspective on the Corleone family tragedy. In 2001, Coppola unveiled Apocalypse Now Redux, a massive and meticulously restored extension of his Vietnamese masterpiece that some critics say eclipsed the already beloved theatrical release. And last year, the filmmaker returned to the catastrophic failure of The Cotton Club for a touch-up that, at the very least, gave the lazy gangster movie a much needed musical boost.

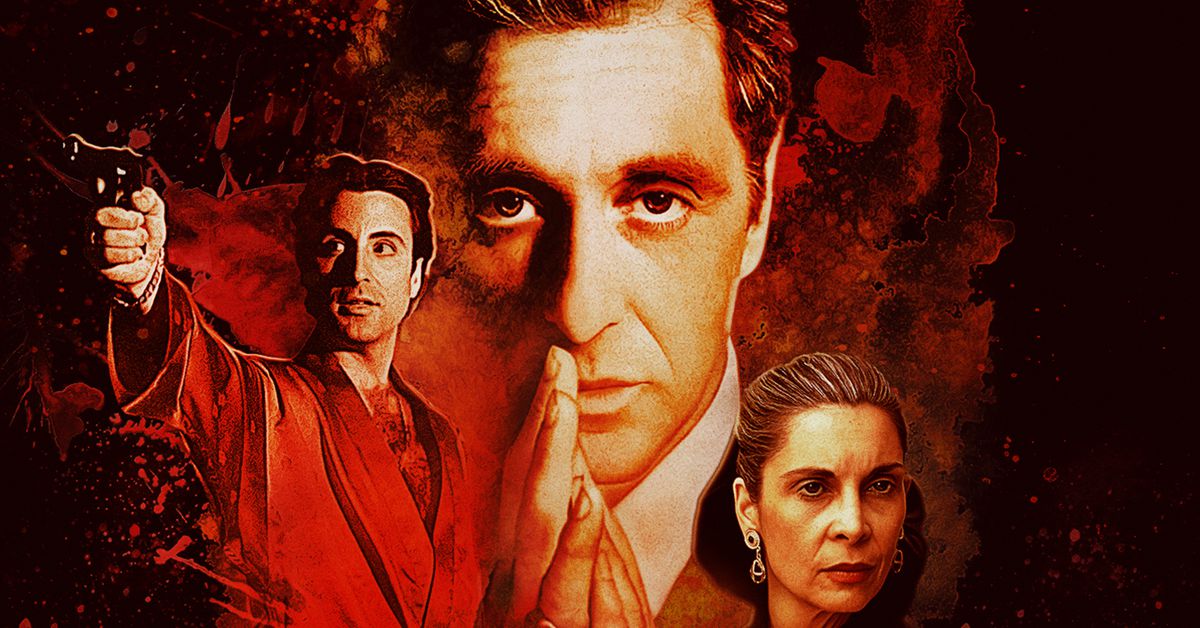

So when Paramount announced earlier this year that Coppola had reworked the 1990s The Godfather III as The Godfather, Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone, there was reason to hope, based on previous successes, that the director had finally addressed some of the nagging flaws of the trilogy corker. But what could realistically be done to improve Sofia Coppola’s awkward performance as Michael’s daughter, Mary, or fill the void left by Robert Duvall when he turned down Paramount’s derisory offer to take over his role? key role of consiglier of the Corleone family, Tom Hagen? Coppola might be the Director’s Cut maestro, but to fully fill those gaps he would have to weave some sort of editorial witchcraft that doesn’t yet exist.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22133339/BD_TheGodfatherP3Coda_OSleeve_2D.jpg)

Image: Paramount Pictures

What Coppola does is less a magical act than an elegant threading of a needle. As he states in his introduction to the inelegant title The Godfather, Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone, the last installment was envisioned as an epilogue to the epic tale of the first two films. Indeed, this expensive title was Coppola’s preferred nickname and The Godfather author Mario Puzo, who partnered with the director on the scripts for the three films. Paramount naturally hesitated at treating the first Godfather movie in 16 years as, in Coppola’s words, a “sum” instead of an event, but releasing it as “The Godfather III(On Christmas Day, no less), they were preparing audiences and critics for a grand finale that the filmmaker had no interest in delivering; Therefore, much of the film’s initial criticism, which was rushed into production to meet this prestigious release date, hammered the film for a slow-developing plot that felt like a retread of its pristine predecessors. Narrative familiarity was not seen as intentional, but rather a sign of creative bankruptcy.

Coppola’s review, which lasts less than 157 minutes, immediately resets expectations by placing its subtitle not only in quotes, but separate from the classic Godfather puppet logo (a first for the series). The opening images of Corleone’s flooded precinct in Lake Tahoe have been replaced with a low-angle exterior photo of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, a downtown architectural antiquity overshadowed by its neighboring skyscrapers – which is shocking considering that the original The Godfather III starts in Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral in downtown Little Italy. What is happening here? Coppola goes straight to meeting Michael with Archbishop Gilday (Donal Donnelly), the overwhelmed and smoky chained leader of the Vatican Bank who is desperately selling the Vatican controlling stake in real estate conglomerate Internazionale Immobiliare to the Corleone family. Previously, this scene had landed after the Vatican-sponsored ceremony and party celebrating Michael for his charities. By repositioning the Gilday scene, Coppola makes the stakes surprisingly clear: Michael is exploiting Catholic Church debt to legitimize the Corleone family business and, not for nothing, become one of the richest men in the world. As the deal is all but done, Gilday sheepishly laments, “It seems in today’s world the power to absolve debt is greater than the power to forgive. To which Michael retorts: “Never underestimate the power of forgiveness.”

Forgiveness. It’s the dramatic deal that Coppola and Puzo chose for Michael in this “coda,” and the film’s loaded plot finally serves a unified theme. Since volunteering to assassinate Sollozzo and McCluskey, Michael has treated life like a chess board; he sacrificed his own brother to subdue Hyman Roth (Lee Strasberg), and accepted the horror of his wife, Kay (Diane Keaton), as collateral damage. According to Peter Biskind’s The companion godfather, Coppola spoke of the last shot The Godfather II, where Michael sits silently outside the Tahoe compound, like “the Hitler scene.” He not only settled all the family debts; he has separated himself from any semblance of a loving family. He is devoid of humanity. Twenty years later, as Michael enters the final act of his life, he desires atonement. For a man who has done so much harm, it seems impossible. But viewers have vivid memories of the man who once said, “This is my family, Kay; it’s not me. ”He had other plans. Could there be a path to redemption for this self-taught monster?

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22133345/godfather3_movie_screencaps.com_1262.jpg)

Image: Parmaount Pictures

From Aeschylus to Shakespeare to Arthur Miller, the answer has always been a categorical “no”. But like all great tragedians, Coppola persuades his audiences to believe that there is a catharsis that could cleanse Michael of his sins and restore the family he sidelined. The passage of time does a lot of work in the film and raises a lot of questions: if the Corleone family was successful enough to buy a controlling stake in the real estate company Immobiliare, what were they doing in the 1960s – i.e. the decade that sparked America’s fascination with the Mafia (and inspired a bestselling book titled The Godfather)? What kind of heat fell on the organization after the assassination of JFK? Do they have really to avoid the lucrative drug trade that flourished throughout the Vietnam War and beyond?

The Michael of The godfather, Coda compartmentalized its commercial misdeeds. He is strangely pleasant. The Immobiliare agreement is terminated, pending the formality of the Pope’s approval. He’s a generation removed from his father’s Little Italy territory – now run by John Gotti-esque Joey Zasa – and he has a savvy publicist (Don Novello) to handle all the thorny press inquiries. He is practically untouchable.

The case may be settled, but for Michael, man of the ultimate conquest, the staff must be faced. This pursuit was clouded in previous incarnations of the film, but, leading up with this scene of Gilday (instead of the church ceremony, which was fully excised), it’s the lonely narrative push of The godfather, Coda. Michael is not joking about “the power of forgiveness”. He believes atonement is possible. He thinks he can reunite his family. He reluctantly sanctioned Anthony Jr.’s opera career and entrusted the Corleone Foundation to Mary. Kay doesn’t want to be a part of this, but Michael, in a new display of vulnerability, allows her to leave a room on her own rather than shut it off. This constitutes growth in the name of the Don. As the action moves to Sicily, Michael pours out the charm. He takes Kay on a tour of her family’s hometown and invokes the memory of the man she once loved (a man viewers barely glimpsed in the first film). It almost works. It helps that Michael has hedged his bets. Although he is delighted if Kay remarries, he will be content not to dread it anymore. The latter seems to be negotiable.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22133350/godfather_3_michael_kay.jpg)

Image: Paramount Pictures

When the Pope’s health deteriorates, the Immobiliare deal appears to be renegotiable, placing Michael at an unexpected disadvantage as he nears his goal of respectability. Michael expected the “legitimate” business world to be less ruthless than the criminal underworld, but, as he confesses to Connie, “The higher I go, the more a con man it becomes.” It is a reversal of the naivety shown by Kay in The Godfather when she said senators and presidents don’t kill men. Michael is on top of his head, and when he sees the sharks spinning, he has no choice but to strike back the old fashioned way. To do this, he must cede control of the family to his nephew Vincent (Andy Garcia), and hope for the best. But even if he succeeds, he now knows that “legitimacy” is an illusion.

Those who hope The Godfather, Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone be a revelation at the level of Apocalypse Now Redux, or a stepping stone to a fourth chapter of the saga, will be disappointed. There are no surprises beyond the first 20 minutes of this version, other than the denouement, which denies Michael the death release he received at the end of previous cuts. His punishment is a long life (“cent’anni”), the very thing he stole from his enemies and, by an unforgivable act, from his brother. Sofia Coppola’s infamous performance is what it is; she does her best with what she gave, which isn’t much. And that’s the unrepairable element of this movie. The parts are there. Coppola and Puzo traced it judiciously. But Mary, whose death is supposed to break our hearts, never registers as a scared child. In a way, that makes sense: she’s been lied to all her life and she’s in love with her cousin. It’s water for psychological drama, and there are times when The godfather, Coda takes on the intimate grandeur of Luchino Visconti’s Sicilian family drama, The leopard.

But that’s Michael’s story. Mary is what happens when a father projects a false sense of principle. She is immune and, as an adult, helpless – unable to navigate a cruel world beyond conception. In that sense, Coppola fixed the film. The coda is a perfect synthesis of his two masterpieces. It’s an American tale. And it’s done.

The Godfather, Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone premieres in limited theaters on December 4; the touch-up arrives at Blu-ray and digital rental services on December 8.

[ad_2]

Source link