[ad_1]

Federal prosecutors had charged Robert Zangrillo, a Miami developer, with a costly and criminal effort to gain his daughter’s entry into USC.

In 2017, Zangrillo hired associates of Newport Beach consultant Rick Singer to secretly finish his daughter’s high school class. Zangrillo later paid others to complete classes at his daughter’s community college. And to get his daughter to accept USC as a transfer student, prosecutors alleged, he opted for Singer’s infamous “side door”, paying $ 250,000 as part of a scheme to falsely choose his daughter as a recruit to the crew.

A trial was scheduled for later this year in Boston on charges of fraud, corruption and money laundering.

Yet in the final hours of his presidency on Wednesday, Donald Trump extended a hand of mercy to the wealthy Florida investor and issued a “full pardon” that appeared to end the prosecution.

The fallout was rapid.

In a statement, U.S. Massachusetts attorney Andrew E. Lelling glanced at Zangrillo for “knowingly involving his own daughter in a scheme to lie to USC,” and said that grace demonstrated “precisely why Operation Varsity Blues was necessary.” in the first place. ”

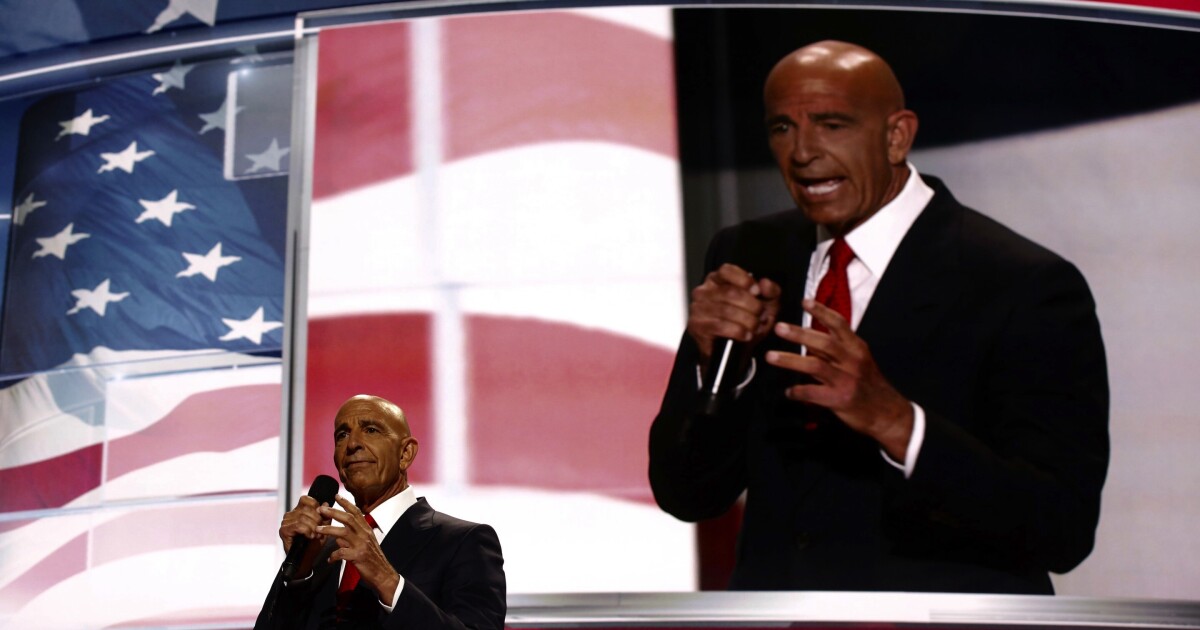

The White House said the pardon was supported by several businessmen, including Los Angeles developer Geoff Palmer, but also investor Thomas J. Barrack, a USC alumnus and college administrator, which shocked the campus and beyond.

Barrack, a longtime friend of Trump who also chaired his groundbreaking committee, denied playing a role.

“Mr. Barrack had nothing to do with Mr. Zangrillo’s grace,” a spokesperson said in a statement. “He never intervened and never spoke to anyone about it. reports to the contrary are clearly false. “

A USC spokeswoman declined to comment on the pardon, even though the university was viewed as a victim of the alleged fraud.

“I hope it is true that a USC trustee, owing a fiduciary duty to the university, played no role in securing a pardon for a wrongdoer whose actions were so damaging. to the reputation of USC, ”said Ariela Gross, professor of law and president of Concerned Faculty of USC, a group of hundreds of professors.

A person familiar with Barrack who was not authorized to comment publicly told The Times that Zangrillo had not met the prominent trustee, but had tried several avenues to get his help with the hospital admissions case. ‘university. Zangrillo was blocked at every turn, the person said.

There appeared to be other questionable elements in the pardon announcement. The White House said Amber Zangrillo “currently earns” an average of 3.9 at USC, but a spokesperson for the university confirmed to The Times that she was not registered.

And Sean Parker, the tech billionaire and founder of Napster, has denied playing a role in Zangrillo’s case, although the White House has included him as a supporter.

“Sean doesn’t know [Zangrillo] and did not request a pardon on his behalf, ”Parker’s spokesperson said.

When prosecutors exposed the college admissions case in 2019, USC was the epicenter of the bribery and fraud scheme, with an administrator, coach, professor, and more than a dozen parents doing facing charges.

Zangrillo’s case stood out. He was the only defendant accused of paying third parties to complete his daughter’s high school and college classes. In court records, prosecutors detailed to what extent the father and daughter were involved in Singer’s scheme.

In a conversation intercepted by investigators, Singer told Robert Zangrillo and his daughter that she would go through the USC admissions process as a sports rookie. After being accepted, Zangrillo sent USC’s athletics department $ 50,000, per Singer’s instructions, and then paid Singer $ 200,000, prosecutors said.

Donna Heinel, a former administrator of the USC athletics department who prosecutors said was part of Singer’s plan, had not classified Zangrillo as a rookie but as a “VIP,” even though she was. not an elite athlete. Prosecutors argued that although Amber Zangrillo was ultimately admitted as a VIP and not a recruited athlete, her father understood that she was being fraudulently introduced to USC as a gifted rower.

“Sir. Zangrillo has abetted, aided, abetted and paid for this fraud on several occasions,” said Eric Rosen, federal prosecutor, at a hearing in 2019.

From the start, Zangrillo waged a particularly aggressive campaign in his defense and sought to expose USC’s admissions practices. His lawyers have fought for a series of internal documents on USC admissions and the role of philanthropy in promoting applicants.

Zangrillo’s legal team also wanted USC to provide a particularly sensitive body of information: the names of prominent figures who fought for certain candidates.

USC and its attorneys for Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher fought not to reveal those names, but a judge ultimately ordered the school to turn the documents over to Zangrillo’s attorneys without redactions, names and everything.

Zangrillo’s pardon could prevent this and other aspects of USC’s confession from being released during a jury trial.

Behind Zangrillo’s pugnacious legal strategy, there was a defense that rested on the theory that USC routinely admitted the offspring of donors and other important figures as special or “VIP” candidates.

“The idea that Robert Zangrillo’s $ 50,000 check to USC, made after his daughter’s admission, was a ‘bribe’ is legally wrong – there was no deal corrupt counterpart between Mr. Zangrillo and USC which brought this relatively ordinary gift to a university in the orbit of federal criminal law, ”his attorneys wrote in a 2019 filing.

“It was a gift indistinguishable from the large number of other donations made by parents of students to USC and apparently to other universities and colleges across the country,” the lawyers added.

While others trapped in the college admissions scandal spent time in jail or lost their jobs, Zangrillo remained active in business.

He is the founder and CEO of Dragon Global, an investment firm, and late last year his attorneys told a judge he was involved in meeting potential investors and exploring for business opportunities in Mexico.

Zangrillo requested permission to travel to Cancun, Playa del Carmen and Tulum for 10 days of business meetings last November. A judge approved the trip.

Times editor Matthew Ormseth contributed to this report.

[ad_2]

Source link