[ad_1]

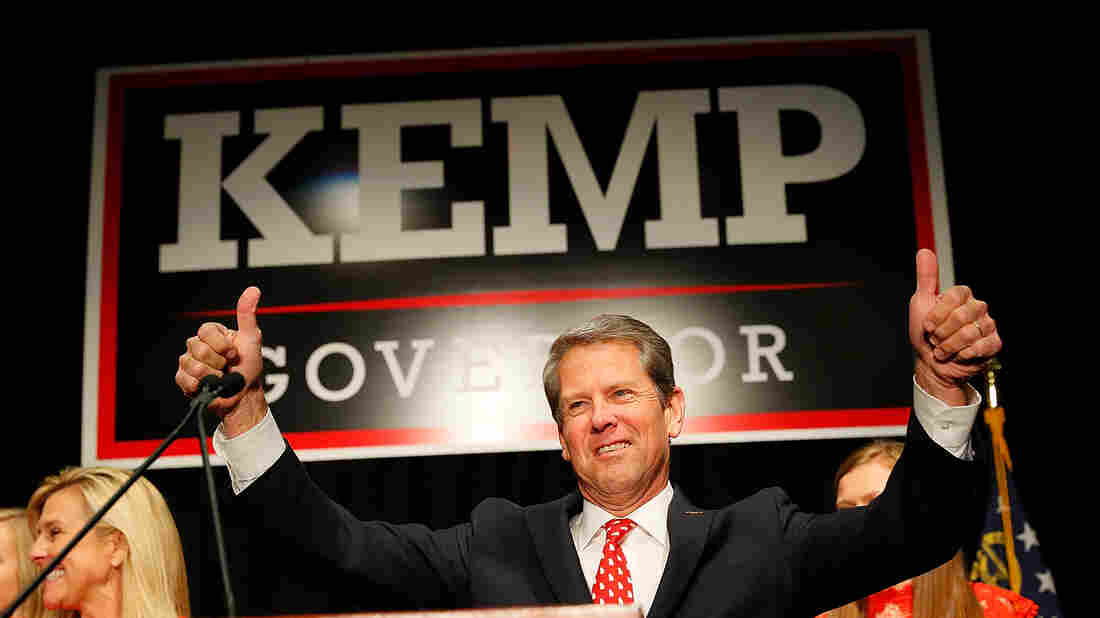

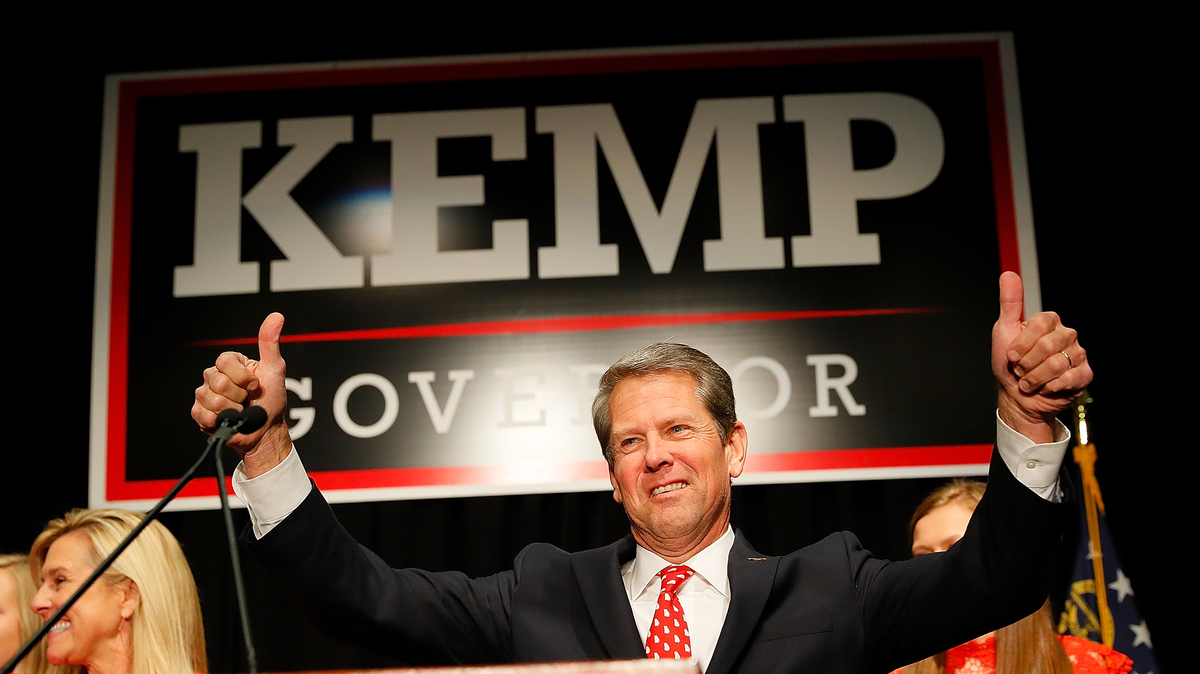

The then Georgian state secretary and Republican candidate for governor, Brian Kemp, attends an election night in Athens, Georgia. As Secretary of State, Kemp was responsible for overseeing election logistics for the elections in which he was running.

Kevin C. Cox / Getty Images

hide the legend

activate the legend

Kevin C. Cox / Getty Images

The then Georgian state secretary and Republican candidate for governor, Brian Kemp, attends an election night in Athens, Georgia. As Secretary of State, Kemp was responsible for overseeing election logistics for the elections in which he was running.

Kevin C. Cox / Getty Images

When Ohio State Election Law Professor, Daniel Tokaji, explains to colleagues from other parts of the world how the United States chooses election officials, he says that he is the only one in the world. they are stunned.

"And not in a good way," says Tokaji.

In fact, in much of the United States, elections are supervised by a leader who is openly aligned with a political party. It is an electoral administration system that is regularly the subject of scrutiny over the last two decades and which was again applied at the mid-term this year, particularly in Georgia, Florida and Kansas.

"Almost everyone recognizes that it is fundamentally unfair for the referee in our elections to also play a role in one of the two teams, Democratic or Republican," said Tokaji.

This is how election administration works in most of the country, according to Martha Kropf, a professor of political science at the University of North Carolina in Charlotte, who is studying the subject.

At the state level, two-thirds of states elect a leader, often a secretary of state, who oversees the vote. And the vast majority of them are supporters. About half of the local election officials are also linked to a political party.

"It sounds bad, in the same way that gerrymandering seems to be bad on a partisan basis, made by state legislatures," Kropf said. "Having local officials elected on a partisan basis to hold elections seems shady."

Mid-term allegations

In Florida, Republican Governor Rick Scott narrowly won his run to the US Senate seat.

While the votes still counted, he called the election supervisors of Broward and Palm Beach counties – Brenda Snipes and Susan Bucher – both elected Democrats (Snipes later resigned).

Scott, who appointed Florida Secretary of State Ken Detzner, said without evidence that electoral fraud was widespread in both counties and asked Florida's law enforcement department to investigate the charges. accusations.

"No group of liberal activists nor SDC lawyers will be allowed to steal this election from the voters of this great state," Scott said after announcing that he had called the police to Law enforcement.

The Detzner office and the Florida Law Enforcement Department said they had found no evidence of electoral fraud and had refused to investigate further.

Even though there was no evidence of professional misconduct on the part of Snipes or Bucher, their political affiliation conferred on Scott, and even President Trump, ammunition to sow doubt even as the votes were always counted.

Brenda Snipes, polling officer in Broward County, Florida, has just been spotted wearing a beautiful dress with 300 I VOTED signs. I'm kidding, she's a very honorable, very honorable and highly respected voting tactic!

– Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 28, 2018

In Georgia, Secretary of State Brian Kemp won his race for governor. But the Democrats regarded many of his office's policies as thinly veiled attempts at suppressing voters.

Between the long queues in the polling stations of the Democratic Districts and the cyber-piracy accusations that have never been successful, Kemp's dual role as election officer and candidate has allowed critics to question the legitimacy of elections.

Kemp himself rejected these accusations, arguing during a debate in October that "no one has made voting easier and harder to cheat in our state … I've actually taken the lead on these issues. "

This week, its opponent, Democrat Stacey Abrams, has launched an ambitious legal action against the state of Georgia, which "will continue its efforts to ensure the responsibility of the elections".

And in Kansas, Kris Kobach served as Secretary of State while he was also unsuccessful as governor.

Kobach has long claimed that face-to-face electoral fraud was widespread in the state and had helped to introduce stricter requirements for voter identification in the state. He also participated in the leadership of the controversial polling commission created by President Trump after the 2016 elections and purported to establish the existence of a widespread election fraud. The committee disbanded without producing conclusions.

Kobach's role as Chief Electoral Officer in Kansas was also closely examined at the primary level.

With only a few hundred votes separating him from Gov. Jim Colyer, Kobach at first refused to recuse himself from any role in a recount. Under pressure, Kobach was finally challenged and declared the winner.

In the general elections, the decision of local clerks to move a polling station located in a highly immigrant community in a less accessible place was seen by some voting rights activists as an attempt by Kobash's allies to suppress potentially democratic votes .

By 2020

In general, partisan election officials can not change the rules of an election when it is in progress. But they interpret these rules, and this interpretation is important when margins are tight.

According to Krupf, the partisanship of election officials can influence factors such as the manner in which provisional ballots are judged and even how quickly election officials respond to voters' demands.

Let us be clear – in the vast majority of jurisdictions with partisan election officials in Florida and elsewhere – there seems to be no indication that elections are unfair.

In Florida, the allegations of partisanship this year eclipsed what was actually a successful election, said Susan MacManus, professor of political science at the University of South Florida.

"The sad part of all this election for Florida is that there are a lot of fantastic supervisors," MacManus said. "But that sort of left behind, people have never seen this picture."

One of the central themes of the vote administration is that the appearance of fairness counts as much as anything else. MacManus says she's even spoken to election officials who admit that "it's a bit uncomfortable" to hold elections while being affiliated with a party.

Polls show that when most voters consider the issue, they want election officials to be non-partisan.

However, given that states administer elections, a fundamental change in the system would require the updating of state laws across the country. Development experts do not realize so soon.

"It's a question of democratic legitimacy," said Tokaji, a professor at the Ohio State. "In other words: do we have a democracy that really deserves our trust when we have the perception and sometimes the reality that election officials organize elections so as to favor their people and their party?"

[ad_2]

Source link