[ad_1]

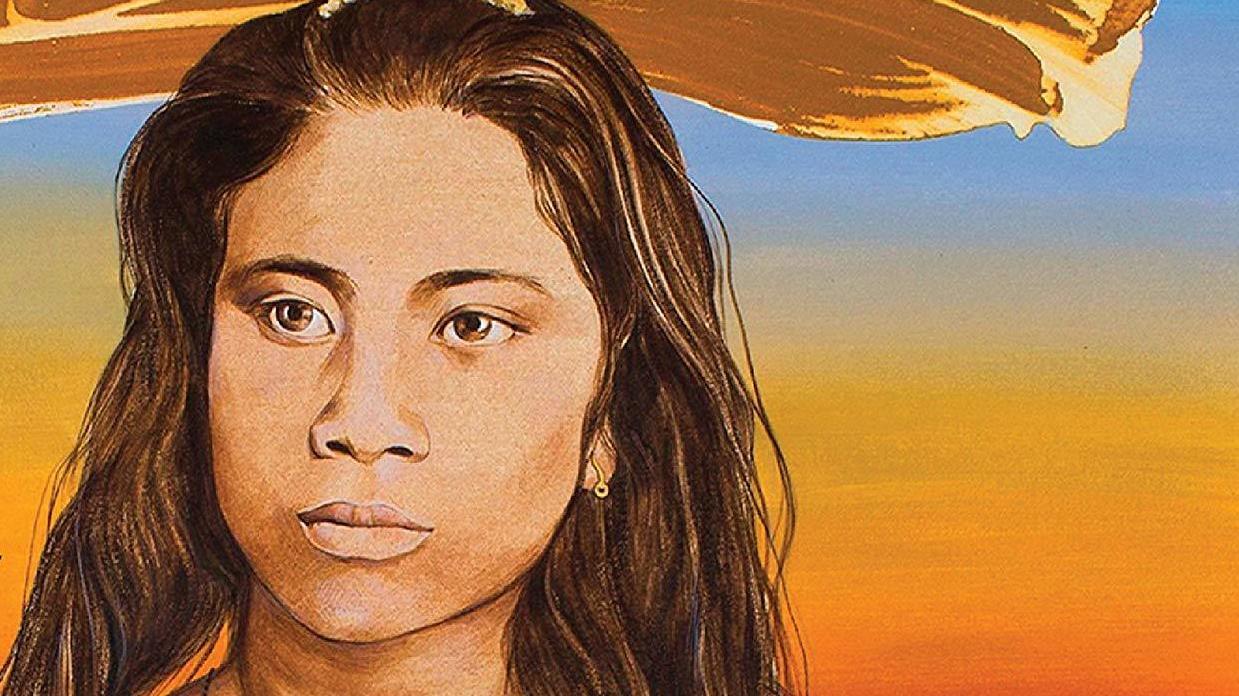

Gina Apostol’s new novel, Insurrecto, is about two women on a trip to make a film in the Philippines. Except they wind up seeing different films in the same characters.

Chiara Brasi is an American who wants to make a movie about an event during the Philippine-American War. She hires an interpreter named Magsalin, who takes her to the island of Samar — and specifically to the town of Balangiga, where Philippine rebels were massacred in a retaliation for an attack on U.S. forces in 1901. Magsalin reads Chiara’s script and writes a different story.

Apostol uses an array of literary and cinematic techniques — memoirs, jump-cuts, close-ups and reveries — to set a story in the present-day Philippines of Rodrigo Duterte.

“I’m very interested in that concept of multiple ways of looking at things,” she says in an interview. “You know, this notion that in all of us there are multiple identities, you know, and we don’t recognize the simultaneity of them. I’m a mom, I’m a daughter, I’m a teacher, I’m a writer, I’m a Filipino, I’m a American. And I really like this kind of seeing things from various points of view.”

Gina Apostol won the PEN Open Book Award for her last novel, Gun Dealer’s Daughter, and has won the Philippine National Book Award. Her newest book shows us that although victors often write the histories, survivors and artists can revise them.

Interview Highlights

On the dueling perspectives

Well, what I wanted was a kind of confusion of their ways of looking at these matters, because as a story — I mean, the story of the Philippine-American War, you know, you have that seeming binary, the colonizer and the colonized. But for instance, myself, as a Filipino, I recognize the colonizer in me, you know. I speak English — I mean, I grew up learning in English. And I thought it was very important also for the colonizer to also have that recognition of the voice of the colonized in it.

I think it’s important, for instance, for an American to recognize its multiple histories. You know, this history of wanting to be the liberator in the Spanish-American War period, but also recognizing the inhumanity that came from that war. So there’s this tension of the two.

On Casiana Nacionales, the real-life insurrecto of the book’s title

History barely knows. And even say when I went to Samar to ask about her, there was very little known about her. But I think the figure of Casiana Nacionales — I think she resolves that dilemma of multiple seeing. Because just because we need to see in multiple ways does not mean we don’t take a side. That there’s — that this confusion of empathy with ethics sometimes is problematic, because yes, as a writer I empathize with my character, the U.S. soldier, Army soldier; I empathize with the white woman photographer. But I also recognize that for my novel, Casiana Nacionales is the heart of the story — that we need to, in some ways, side with her revolutionary rage.

Because I think atrocity happens, this war happened, because of the inability of, let’s say, the invaders, the U.S. Army soldier, the white woman photographer — all of whom I empathize with — could not imagine the agency and aspirations of Casiana Nacionales. So the way she’s put into that story, which is spiraled through layers and layers of narration, I think is/was, for me, a way to resolve my own dilemma about empathy and ethics.

On the humor in the book

You know, I’m really so grateful that you bring that up because I think it’s not very clear, you know, to people that when you’re writing a political novel, that — really, I mean, this novel has very clear political stakes — that you can’t be playful with it too, you know? That you’re put in this little box of being a political novelist, but the fact is: There’s so much you can do as a writer with story. And I’m so glad you mentioned the humor. I’m glad that came through.

On the presence of Elvis in the book

The thing about Elvis is that I — you know, I didn’t like him because he was my mom’s favorite. But it was only a few years ago that I realized that all these songs that my uncles, when I was a kid, would sing — this is in the ’70s — would sing for, like, long long long guitar-strumming fests, were actually all Elvis songs. So I actually thought Elvis was Filipino for a long time. …

So I really started thinking about: What does that mean that I think Elvis is in me also? You know, what does that mean about this history of colonization? What does that mean about all of us that we’re not just one thing? We’re so many different things! I have Frank Sinatra; I have Elvis; I have Virginia Woolf; I have Dante; I have also Balangiga; I have, you know, Iluminado Lucente, the Waray [language] writers; I have José Rizal. We’re all so many things, and it was that Elvis recognition — I go, “OK.” So I put him in.

On how being a schoolteacher affects her writing

It does fit in very — I mean, I just taught Frederick Douglass’ “What to [the] Slave Is the Fourth of July?” I just taught the Constitution to my little 15-year-olds. And I teach the Filipino-American War to my students, because the way I talk about it with my students: You hold these tensions in your country, and it is good for you. It is good for you to recognize the liberatory aspects of the “saving principles,” as Frederick Douglass called them, and it is good for you to recognize that there was inhumanity in our original Constitution — that there was a three-fifths clause, that there was a normalizing of genocide against Native Americans. And to hold those together, and to confront that daily — it’s really very difficult — but to hold those tensions together is a way to be a healthy American. And I think that’s why a book like Insurrecto would be useful, is because you can see all these different sides. And so it’s a Filipino book, it’s an American book, and to recognize that these are all part of this nation.

And for the students to be able to hold these tensions and from there, think about: OK, what is the ethical move? You what is the ethical move you make when you recognize a more full sense of your country? It’s not this exceptional singularity. It’s an interesting plural. So I teach these things to my students, and I think that we should use these liberatory aspects of the founding documents to counteract the inhumanity that is also part of this history. So I think as a teacher, it’s just — given the difficulty of our times, it’s also kind of liberating for me to do the work that I do as a novelist that’s not at all separate from the ethical reader that I want, and the ethical citizen that I want in my classroom.

Sarah Handel and Barrie Hardymon produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Patrick Jarenwattananon adapted it for the Web.

Source link