[ad_1]

Just as lowly Peter Parker was bitten by a radioactive spider and humble Bruce Banner was blitzed by gamma rays, so every Stan Lee devotee has an origins story to tell. One minute they’re just another a puny schoolkid. The next – ka blam! – they’ve been singled out. They encounter a comic glowing radioactive on the bottom rack of the newsagent’s, or lurking at the dentist’s waiting room – and from that moment on, their lives are changed. Inside the covers, muscled freaks of nature tackle the galaxy’s biggest problems. And yet, crucially, it always felt as if these costumed titans were not so very different from the humble schoolkids who loved them.

Or, to put it another way, for a generation of British fans who grew up in the 1970s and 80s, Marvel was the childhood equivalent of Beatlemania. Marvel cleared the cobwebs with the same insurrectionist force as Twist and Shout or I Wanna Hold Your Hand. It was the shock of the new, an undiluted blast of pop culture that turned the world Technicolor. These days, the Marvel universe extends across merchandise, theme parks and a seemingly endless assemblage of tent-pole Hollywood blockbusters. But back then, the kingdom was largely confined to a weekly roster of superheroes. All of which was entirely fine. We’d been raised on Noddy, Blue Peter and the TV test card. Those characters alone were almost too rich for our palates.

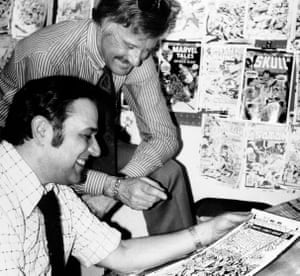

We knew who was responsible. The man was never one to duck credit. Stan Lee became our Willie Wonka, our PT Barnum, our Wizard of Oz behind the curtain. Periodically, he’d show his grinning face. But mostly he was hard at work, marshalling his crack team of writers and illustrators and deploying his super-group of un-jolly green giants and soulful silver aliens.

Daredevil, Black Panther, Dr Strange, the Submariner: there were so many names, one struggled to keep up. So you had to pick your favourites and stick with them through thick and thin. For years, I maintained a subscription for both Spider-Man and The Incredible Hulk. My surname was scribbled in pencil at the top of each issue and kept behind the counter at the newsagent’s each week. These comics retailed at 7p each. Even in infancy, this struck me as preposterously good value. I once wrote to Stan Lee to thank him. I don’t think he ever wrote back.

Born Stanley Lieber to Jewish immigrant parents, Lee started out on the bottom rung of the pulp magazine business, filling the inkwells at Timely Comics in New York. He went on to become a brand name, a juggernaut, a one-man industry, with all that this entails. On the page, for public consumption, he was always “Stan the Man” or “Smilin’ Stan”, at once lovable uncle and creative dynamo. But from backstage came tales of a less edifying alter-ego. It was said that Lee took credit, stole fortunes and relegated key collaborators – such as Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko – to the role of insignificant bit players. Everybody and everything was grist to his mill, first fuelling and then burnishing his reputation as the most influential popular artist of the 20th century.

How influential was Lee? Where does one begin? You can measure his success in terms of bums on seat and money in the bank. The Marvel Comics Universe films have grossed around $11bn and counting. Lee’s own net worth was put at around $80m. Except that none of this would have been possible without the stories themselves – without tales that unfolded with the snap and vigour of cinematic storyboards and came peculiarly attuned to the tensions of contemporary America (whether it be Vietnam, civil rights or the threat of nuclear annihilation).

In the end, of course, it all comes back to the stories. If the western was America’s great founding myth, then Lee’s Marvel was its modern-day legend. Here, in all its Day-Glo glory, we had a fictional universe to set alongside that of Mount Olympus and King Arthur’s round table, full of heroism and anguish, bravery and self-doubt. While there had been costumed do-gooders before Lee came along (straight-edged Clark Kent, rock-jawed Bruce Wayne), his characters felt different. As documented in Michael Chabon’s novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, these were fantasy supermen dreamed up by outsiders. They were a cerebral Jewish immigrant version of heroism in which wisecracks, angst and neurosis were as much part of the package as might and patriotism – and sometimes more so.

There was a darkness and a nuance to all the best Marvel characters. The Incredible Hulk, bless him, is a Jungian case study on steroids, constantly at war with his shadow. Spider-Man is a kind of weaponised adolescence, spraying sticky fluid to the four walls, while Ben Grimm (aka The Thing) is body dysmorphia made monster, a poetic soul trapped in the carapace of a musclebound roughneck. These men (Marvel’s main failing is that it did mostly do men) have the power to turn the world on its head. But they also seem as much cursed as blessed.

Naturally, I kept my Marvel subscription going for years, as the price climbed first to 8p, then into double figures. And then, just as naturally, I let it lapse – moving on towards music, big books and the storm of adolescence. Except that, in the week of Lee’s death, I realise that no one ever truly moves on – first love marks you for ever. All those years I’ve spent loftily saying that the first great adventure story I read was The Lord of the Rings, and the first great teenage portrait was The Catcher in the Rye – what rubbish that now turns out to be. It was the Silver Surfer, Spider-Man and all the rest of them, too. Marvel taught me how to read, how to think. Possibly it still does to this day. Show me a glossy cover by John Buscema and I’ll start salivating.

“If you want to send a message, call Western Union,” said Hollywood mogul Samuel Goldwyn, a man who believed that popular entertainment dies the moment it turns into a lecture. And yet looking back now, from the vantage of middle-age, it feels that Marvel sends a pretty glorious message to the puny kids who blunder into its universe just before the hormones kick in. It tells them that, yes, they possess super-powers. That they can impact the world, that adulthood’s an adventure. But it also says that, guess what, your life will still be a mess. Your increased speed and strength will throw up a whole new set of problems and that gaining great power brings great responsibility.

In which case, the best course of action is to be good and be kind. Fight injustice at every turn. Raise up people when you see they’re in need. Listen to the angels of your better nature. That way you too can emulate Marvel’s greatest heroes, be it Spider-Man, Daredevil or Stan Lee himself.

Source link