[ad_1]

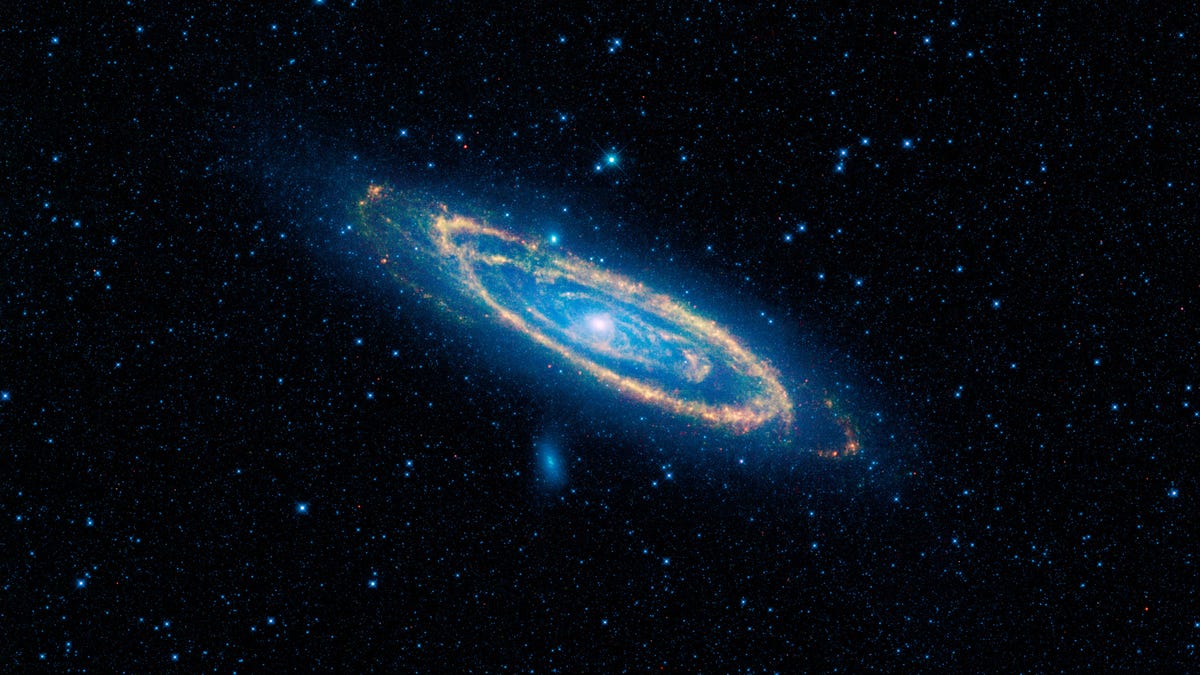

On the night of November 23, 2014, a powerful telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii was attempting to locate the enigmatic movements of a black hole traversing space. In the seven hours that the telescope scanned the cosmos, it may have caught one, as an Earth-sized structure eclipsed a star in our nearest galactic neighbor, Andromeda, at around 2.5 million light years. Amid the 188 relatively bland images taken of the galaxy that night, the candidate black hole event was a moment of literal enlightenment.

“When it’s right along the line of sight, the light bends [the black hole]. Not only the rays of light that indicate you are with, but also those that have passed you are leaning towards you, ”said Alexander Kusenko, astrophysicist at UCLA and the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe. , in a video call. “It will make the star brighter for a second. It’s a bit counterintuitive.

Kusenko is the lead author of a recent article on the event, published in the journal Physical Review Letters in October. Research suggests that between some and all of the dark matter in the universe could be explained by primordial black holes – small and very old hypothetical versions of the classic cosmic figure who was only imaged directly for the first time in 2019. All black holes, regardless of their size, are celestial objects that exert such a gravitational force that nothing, not even light, can escape them.

One idea is that at the start of the universe, slight fluctuations in density in the incredibly dense swelling universe would have been enough to spawn black holes from the pre-stellar plasma, especially if they interacted with heavy particles via a force. unknown. (Run-of-the-mill, known black holes are typically made up of collapsing stars.)

“If you take a spoonful of primordial plasma, it’s almost a black hole,” Kusenko said, referring to the initial density of the universe. “Squeeze it a bit, and the light won’t escape.”

G / O Media can get a commission

Some of these theoretical black holes would have been of a critical size, in accordance with Einstein’s theory of gravity, to be seen to continually extend to an observer in the black hole – while remaining a static size for the outside observer. This idea may spawn notions of a “baby universe” in our own, but keep in mind that primordial black holes themselves are purely theoretical for the time being.

And that’s the immediate concern of Kusenko’s team: proving their existence. Primordial black holes would have to be numerous if they were to represent a certain amount of dark matter in the universe – a mysterious substance that appears to make up about 27% of the universe – but too small to be detectable, as were their confirmed counterparts.

Kusenko and his colleagues (the October paper involved researchers at UCLA and Kavli IPMU) cast a wide net for black hole candidates using the Hyper Suprime-Cam, a lens barrel of nearly 6 feet long attached to the nearly 30 foot mirror of the Subaru Telescope on Mauna Kea. The camera is able to image the entire Andromeda galaxy every few minutes. Since a candidate for a primordial black hole was chosen during the seven-hour tour of the cosmos in 2014, Kusenko hopes that future observations will be able to collect more events to unbox.

The 2014 observation was not easy to find in all of the data. This team narrowed down a catalog of more than 15,000 candidate stars to verify the distortion of light, and found nearly 50 “impostor” events, caused by bright stars, among others. An impostor was even caused by a passing asteroid. But after a lot of star-sorting, a candidate seemed bona fide.

If more candidate events are identified, there will be more lead to the team’s theory of many miniature black holes representing the excess gravity measured in many galaxies (it was this extra gravity that alerted scientists to the existence of dark matter in the 1970s). To put it in perspective, the smallest known black holes are in the domain of 5 solar masses (or five times the size of the Sun). The recent candidate black hole was only the size of our planet.

If an Earth-sized black hole seems hard to believe, well, it’s not even the smallest black hole on offer. Last year, physicists suggested a black hole the size of a bowling ball to explain a hypothetical object in our solar system known as Planet Nine.

Kusenko’s team made another round of sightings at Mauna Kea at the end of 2020, and now they have to do the meticulous work of filtering the data. We might know later this year if they’ve found any potential black holes– and our fingers are firmly crossed for good news.

[ad_2]

Source link