[ad_1]

A supermassive black hole recently discovered, 13 billion light years from Earth, could eventually provide us with valuable information about the formation of the universe. Meanwhile, this only confuses Eduardo Bañados – the astronomer Observatories of the Carnegie Institution who found him. He describes his perplexing work this week in a pair of articles in Astrophysical Journal and Astrophysical Journal Letters .

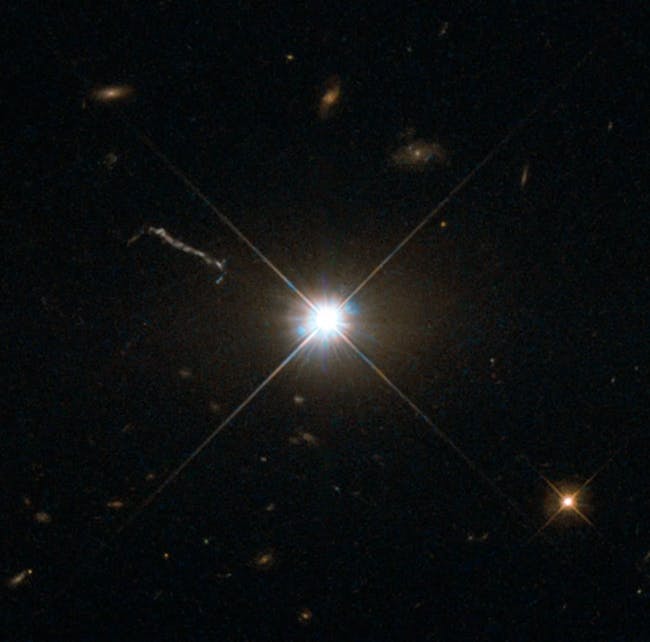

"There are perhaps 200 quasars that are at similar distances, but the peculiarity of this object is that it is extremely bright in radio waves," said Bañados Inverse . A quasar is a galaxy with a supermassive black hole in its center that constantly sucks and spits stellar debris in the form of high energy particles. These particles, moving at a speed close to the speed of light, are so hot that they generally emit a lot of light and radio waves, appearing very bright from the Earth. But this one was abnormally true. "To be honest, at first I did not think it came from the quasar," says Bañados. "It was too loud, I had never seen a transmitter so powerful when the universe was so young." According to him, it is the brightest quasar of the "I". primitive universe by a factor of ten .

The fact that radio waves emanate from this supermassive black hole – which forms a quasar labeled PSO J352.4034-15.3373 (P352-15) with the galaxy fired into its orbit – are unusually "loud" or "bright" means that the quasar itself was atypically dense and active for something that existed at the beginning of the formation of the universe. During the first billion years – the era of reionization – giant stars 30 to 300 times the size of our sun began to illuminate the vast darkness and, in the process, re-energized a much of the inert gas that floated Big Bang. P352-15 could have a level of brightness comparable to these stars, but it is much larger than 300 times our sun.

"How can you form a supermassive black hole that is like a billion times the mass of the sun in less than a billion years?" Bañados keeps wondering. "It's really difficult."

After finding the quasar, Bañados collaborated with Emmanuel Momjian of the National Observatory of Radioastronomy (NRAO) in Socorro, New Mexico, to use the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) of the National Science Foundation. a better view of all that P352-15 is actually (or was). The results of this work were published this week in the Astrophysical Journal and Astrophysical Journal Letters .

With some work, the VLBA has produced a radio-crisp visualization of the quasar, which has three main components with a few distinct features of their own. The total distance between these three components is about 5,000 light-years. "Crisp" here is relative;

He and his colleagues have two ideas about what could happen with P352-15. In one interpretation, they see a bright nucleus with a supermassive black hole in the center, with two other visible parts being the jets of particles that it produces while moving in opposite directions from each other. In another view, the black hole core is on one side and the two streams of particles are moving in the same direction, concentrically.

The team hopes this is the last case as it means that they could potentially observe this one-sided jet. as it develops over several years. "This quasar may be the farthest object in which we could measure the speed of such a jet," Momjian said in a prepared statement.

Despite the fact that quasars are by definition the combination of a supermassive black hole and the galaxy that they consume – and that black holes eject large streams of radio-emitting particles at the speed light – only about 10% The quasars, including this one, are powerful radio transmitters. At least right now, nobody on the ground knows why.

"It's a very active area of research, and we still have no definitive answer," Bañados says. "Whenever we find a system with quasars, it's a puzzle – we do not know how to train them."

In the future, the group hopes to use this new quasar to investigate "the role of radio jets for the formation and growth of supermassive black holes" – how you could tell a writing institution Don's the disturbing fact that P352-15 totally fucks with the way astrophysicists thought these celestial objects were formed.

"This jet must be about 10,000 years old [old]," says Bañados, "which seems a lot to us, but to form a supermassive black hole in less than 10,000 years is a big challenge for the theory of supermassive black holes . "

Thus, this new quasar could tell us a lot about the formation of the young universe or what was happening in the first billion years after the big bang, but it could also simply upset what we thought to know.

"There are some things that we do not know and sometimes people look at scientists and are like," Oh, they should know all the answers, "says Bañados," but that's why we do research. "

"When we do this, most of the time, instead of finding answers, we find more questions."

[ad_2]

Source link