[ad_1]

Richard Williams has been active for 74 years. Here is the first animation he made at the age of 12 years. pic.twitter.com/XKWoOe6ls0

– cartoonbrew.com (@cartoonbrew) August 17, 2019

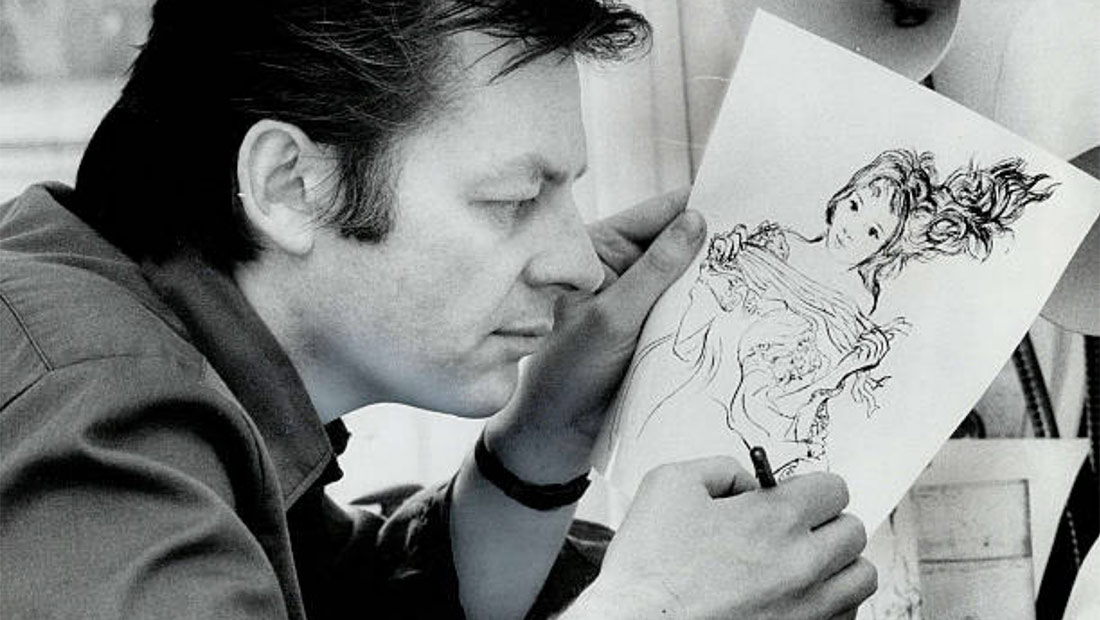

He was the incarnation of the idea that life is a marathon, not a sprint. The documentary published below, dating from 1967, shows Williams as a successful 34-year-old professional filmmaker. At this point in his career, he won a BAFTA and ran a successful commercial studio in London. For many, this would be a sign of having done so. But as Williams often thought about that time in his trip, he really felt that he knew nothing about animation. he was just starting.

For Williams, learning was not something you did as a teenager and then started a career; it was a mission of a lifetime. It's a trip that most do not have the physical or mental means to go on for so long, and it's both inspiring and intimidating to see someone who has accomplished so much before the age of 35, but whose work still has no place to do it. even approaching what he would accomplish in the second half of his life.

I asked him a few years ago how he had kept his skill level in his ninth decade. He attributed it to his ongoing study of the drawing of life. "It's the hardest thing to do," he told me. "When you come out for six months and come home, you realize you're an idiot. That's why people do not come back on it. They say, "Oh, I did it at art school. We do not do it anymore. And then, you're caught with cartoons.

Williams' career has many remarkable accomplishments, but for my money, the most important in terms of impact on the industry has been his job as director of the animation of Who wants the skin of Roger Rabbit. In today's world, where almost every big movie is a virtual movie show or a fully animated film, it's hard to say how much the cinematic landscape was different in 1988 or the phenomenal success of Roger Rabbit intended for animation. It's the film that has set the wind in the veil of animation and has dragged us into this modern era of animation / vfx – its huge sum of 350 million US dollars and more in the world has awakened the Hollywood idea that the general public accepts movie animation if the storytelling was smart.

But Roger Rabbit very easily could have been a disaster in the hands of another director of animation. The integration between the animation and the real action was more complex than anything that had been tried until then, and its realization would require rare know-how in the late 1980s. One of the, if not the only, animation director of the time able to achieve something as crazy and ambitious as what the film was asking, and his feat does not go unnoticed. He not only shared the Oscar Award for visual effects with other vfx artists, but also won another special feat, Oscar, for his direction of animation.

Last year, when I hosted a conference with Williams in Annecy, I said something that I will repeat to the public: Williams is the only contemporary animator to have, in my opinion, built on the legacy of the classic approach of Disney characters. animation and added that animators like Grim Natwick, Art Babbitt, Frank Thomas, Johnston Ollie, Bill Tytla, Milt Kahl and Marc Davis have made a generation before him. He knew them all and worked closely with some of them. But he did not just copy their principles. He developed their pioneering work and changed the artistic form to ever greater heights. His last short film, Prologue, released in 2015, is a graphic masterpiece that pushes its technical mastery further than ever. As he told me in 2015, "I just reached the point where I could associate my work as a draftsman with animation. It has always been a battle for me. "

In fact, it may be Williams' greatest legacy: setting a technical standard for the hand-drawn animation profession. We know what's possible and how we can benefit from it, thanks in large part to Williams' dedication to pushing the limits of the craft and expanding its boundaries.

What is equally remarkable in his career is that he set new standards regardless of what he was doing. Artists tend to compartmentalize their work: it is commercial work and I will only do what is necessary to deliver on time and on budget; it's a personal project and I'm going to make it beautiful. Not so with Williams. His standard always was excellence, whether it produced an advertisement, a special television show, a movie title or an animated feature film. His work never gives the impression that something is just a job or that it does not matter. It is a remarkable ideal to defend – treat each animation with the same dedication and commitment to creation. How do you do that for 60 years without exhausting yourself? I just can not imagine.

But here is the trait that distinguishes Williams from other great: his generosity. He was not selfish about what he had learned, and he did not believe that he was elected or that he was the only one able to create this guy working. He wanted everyone around him to aspire to an exemplary level of profession. During the glory days of his company in London, his outfit was as much a school as a production studio. He has invited countless big names in animation to lead workshops in his studio and to accompany and inspire the new generation of artists. After closing his workshop, he doubled his education efforts, teaching master classes around the world. Later, he compiled this knowledge into The survival kit of the animator (2001) which, in less than twenty years, has become an iconic reference work for anyone aspiring to create this standard of animation.

One of the great honors of my life was to moderate a conversation with Williams last year at the Annecy Animation Festival. Here is someone who participated in the very first editions of the festival, and yet, he seemed as sincerely excited and excited to be in Annecy in 2018 that he was probably fifty years ago. The day before our public interview, we had a three-hour dinner and, with a sparkle in his eyes, told stories I had never heard before. He knew that I was writing a book about Ward Kimball and I was surprised to find that he was just as excited about hearing new stories about Kimball as talking about his own. experiences. With Williams, we feel that animation has never been a career or a profession, but a way of life, a religion and until the end, he never had enough.

There is so much more to say about his work and his life. For the moment, let's share some of the thoughts of the film and entertainment community that are flooding Twitter with their tributes to Williams:

I just realized that Richard Williams has passed away. A huge guide to how we approach our art and continue to redefine it. Let's keep that spirit alive and keep getting things done like never before, okay, guys? #RichardWilliams https://t.co/EAtmTXJO5n

– Scott Morse (@crazymorse) August 17, 2019

Richard Williams was without a doubt one of the greatest visionaries of animation. his work not only set a standard that others could only hope to try to respect, but also truly challenged and explored the capabilities of the media as we know it. rest in peace man. pic.twitter.com/pnKfugNXZ7

– Justin mr. morgan (@j_dubba_m) August 17, 2019

Richard Williams has been and will always be an inspiration for generations of animators around the world. His passion is still alive. https://t.co/0nS9aqSnPk

– Nora Twomey (@ nora877) August 17, 2019

Farewell Master Host Richard Williams. These sequences of titles counted a lot for me in my childhood. They still do it. https://t.co/0RVBIo6tD0

– edgarwright (@edgarwright) August 17, 2019

I am really sorry to hear about the death of Richard Williams. He was one of the best and inspired so many people. pic.twitter.com/IauRI3HkzM

– Aaron Blaise (@AaronBlaiseArt) August 17, 2019

The animation industry has lost a titan today. Richard Williams had a profound effect on the art form. I have personally worn the wisdom of his books and his appearances for decades in my career. Thank you Mr. Williams. TEAR. pic.twitter.com/p5qEqmnkCp

– Everett Downing Jr. (@Mr_Scribbles) August 17, 2019

I am absolutely empty. Without Richard Williams, I do not think my life would have been the same as today. He was beyond an inspiration. His work will live forever. Rest in peace and thank you for everything you have contributed to the world of animation. @RWAnimator pic.twitter.com/rQpGfFnHqT

– Sabrina Alberghetti (@TheRealSibsy) August 17, 2019

I really can not begin to express the inspiration and influence of Richard Williams on myself and so many other animators driven by his passion and vision of our artistic form. A true legend has passed.

– tomm moore (@tommmoore) August 17, 2019

That's right, Richard Williams has democratized animation. I was 14 years old in Chile and I had no access to any courses, but I managed to find a way to get the survival kit on Ebay for under $ 30. Rest in peace and thanks for everything ✨ https://t.co/yRXxKg8wvk

– Fernanda Frick H. (@FernandaFrick) August 17, 2019

Rest in peace Richard Williams … .Master of animation, historian, and the most important figure in the recording and preservation of animation methods to have ever lived. pic.twitter.com/dWw9uT0i8i

– Nick Kondo 近藤 (@NickTyson) August 17, 2019

Richard Williams set the bar so incredibly high for what animation can / could be, and strived to continue perfecting his art until the end, which is the way by which all the great artists leave this earth.

– Michael Ruocco (@AGuyWhoDraws) August 17, 2019

So sad to hear the passing of Richard Williams. He seemed perpetually young and excited by life – fascinated by his capture through animation. I saw him last winter at a Bafta night, full of passion for life and for the film he was working on. TEAR

(His drawing of himself and Milt Kahl) pic.twitter.com/mTelje4KgT– Brad Bird (@ BradBirdA113) August 17, 2019

Richard Williams was our Michelangelo

– don hertzfeldt (@donhertzfeldt) August 17, 2019

RIP to a giant and true visionary of the medium. Thank you, Richard Williams. https://t.co/KidXbVhxPa

– Peter Ramsey (@ pramsey342) August 17, 2019

From pink panthers to screw rabbits to heroes trapped in complex worlds such as Escher's, Richard Williams' uncompromising work spans several genres and styles and demonstrates his unwavering dedication to animation. There will never be another like him. TEAR. pic.twitter.com/XCKBl9hxiI

– Shannon Tindle (@ ShannonTindle_1) August 17, 2019

Very sad day for our industry. A major figure has passed away. @RWAnimator #RichardWilliams was and is a giant of the industry. His work has inspired many of us who are working and trying to break into this crazy company. His love for infectious animation #RIPRichardWilliams pic.twitter.com/ztaGRQBILl

– Jamaal Bradley (@JamaalBradley) August 17, 2019

The death of Richard Williams is a huge loss for the animation community. I do not know of one student who does not mention the survival kit of the facilitator at the beginning; it can be a religious text as well. Rest in peace with a legend. pic.twitter.com/CWOMok2kY1

– Betsy Bauer (@bauerpower) August 17, 2019

A giant from our community has left us. Once in a generation, talent changed what animation could be and how it was perceived forever. Thank you for all your wisdom and inspiration. A legend forever. You left the animation better than you found it. Gracias, maestro Richard Williams. https://t.co/KYErAmWt4G

– Jorge R. Gutierrez (@mexopolis) August 17, 2019

Rest in peace Richard Williams, I heard your voice every day while I was teaching at school and you've always helped me stay on track for animation . Your animation techniques have had a tremendous impact on many lives. https://t.co/n09BxxafX0

– Mii (@OrdanaVii) August 17, 2019

I never had the courage to say hello to him, but his speeches, especially the one he gave to Cobbler in London (in a special session), were a source of inspiration. take a pencil and draw … rip master

– Paul Williams – リ ポ ポ ー ル (@artporu) August 17, 2019

One of my favorite Richard Williams has directed some animation pieces. There is so much joy and passion in his work. An inspiring reminder of all that there is to learn. https://t.co/Zc4pb7fbZt

– Adam Paloian (@adampaloian) August 17, 2019

Richard Williams

1933-2019 pic.twitter.com/jiGvvzis7p– Dave Alvarez (@DAlvarezStudio) August 17, 2019

In honor of Richard Williams, make your next shot something you have never done before. If you can, do something that no one has ever done before. It's ours now. #RIPRichardWilliams

– Chris McCormick (@flatTangent) August 17, 2019

[ad_2]

Source link